(Part I)

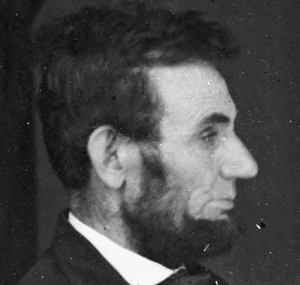

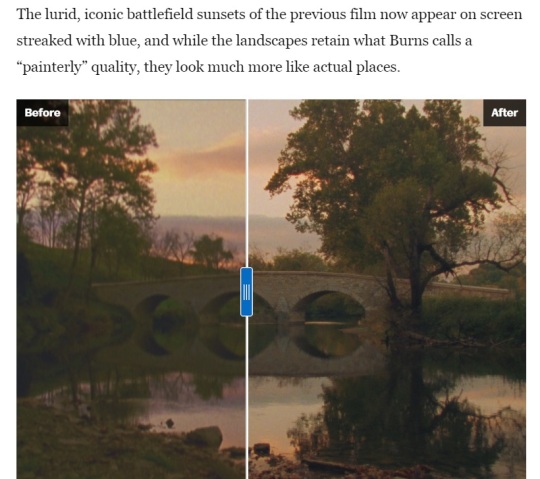

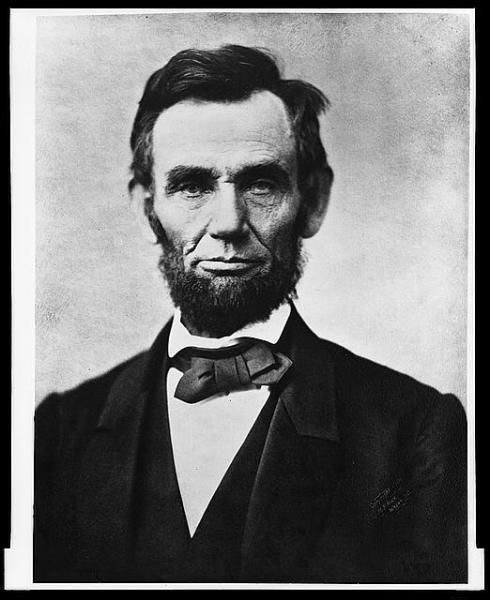

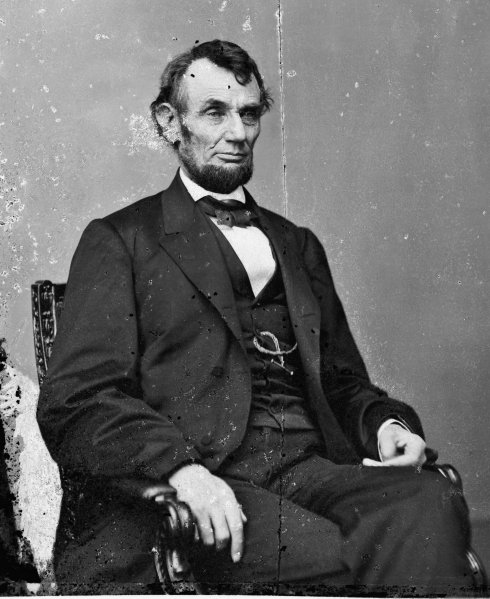

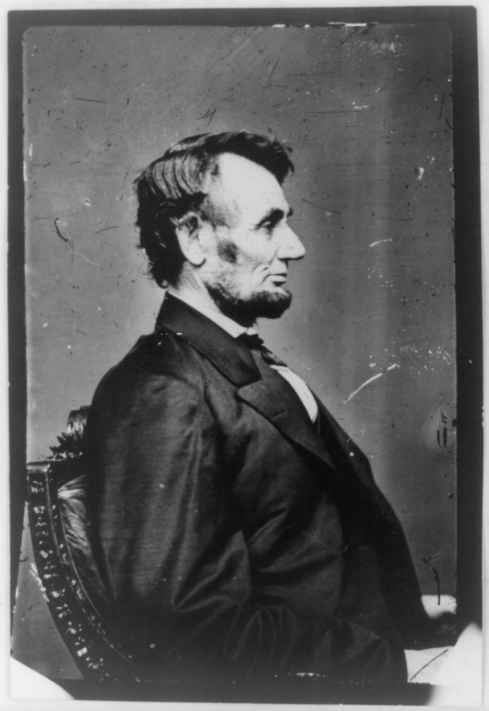

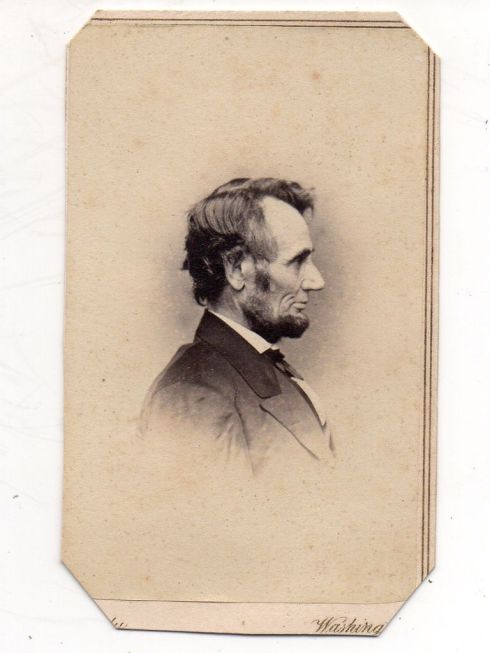

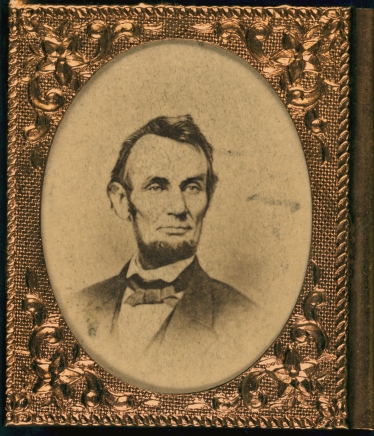

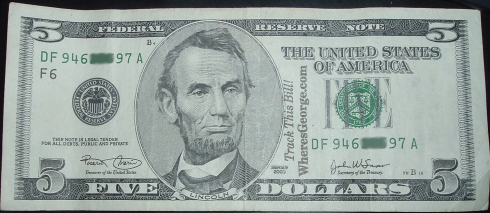

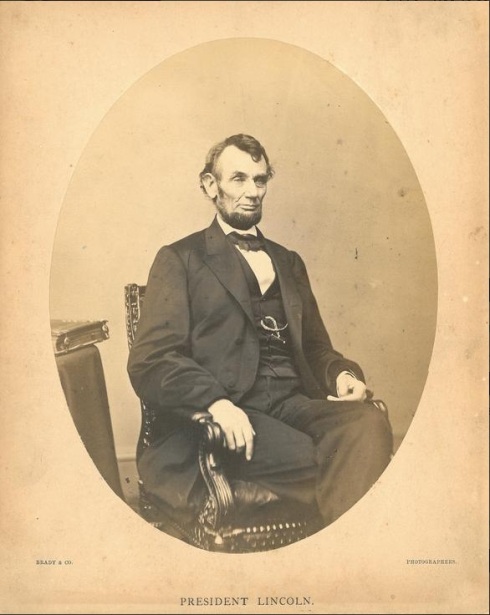

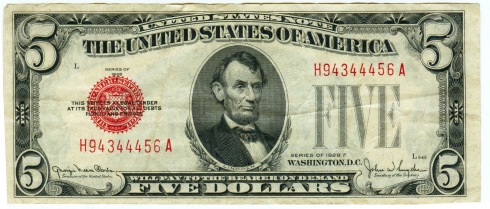

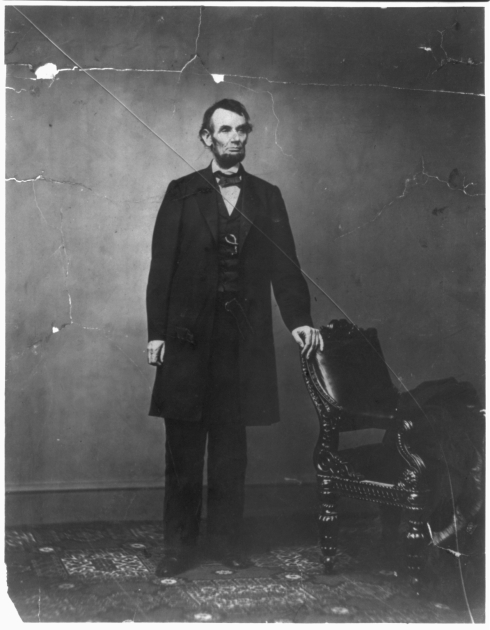

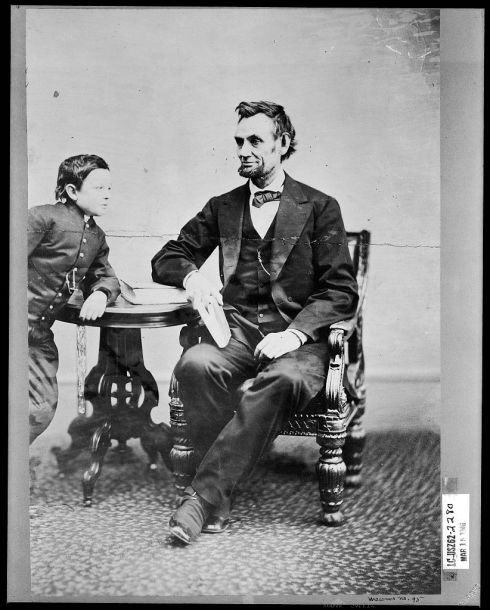

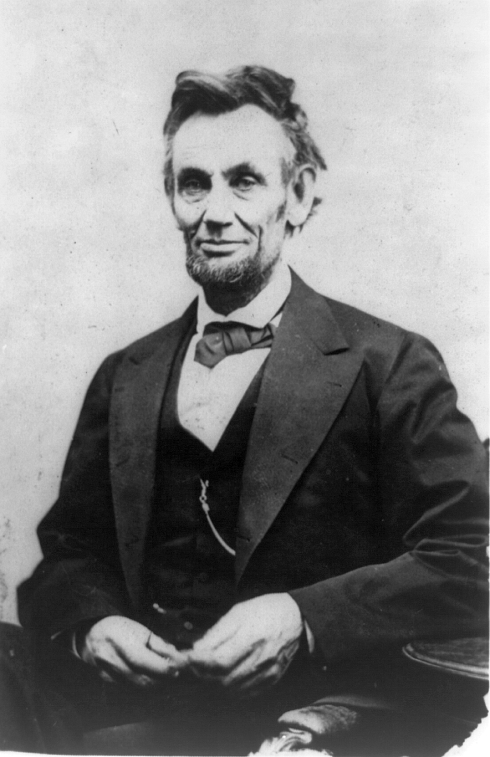

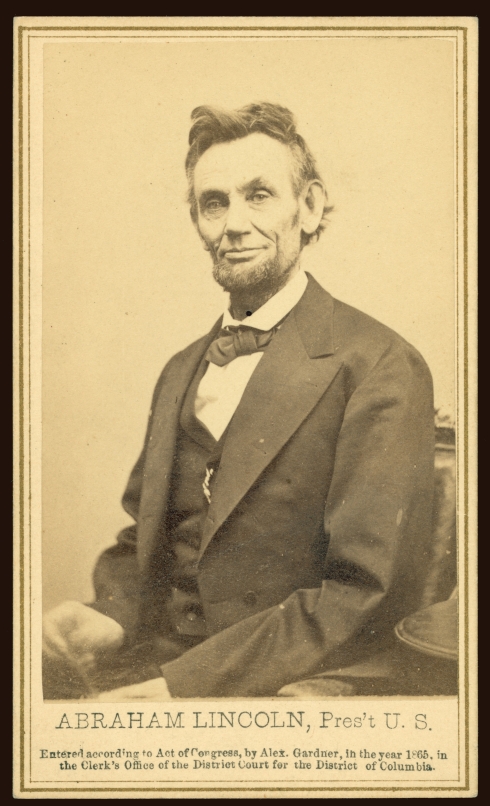

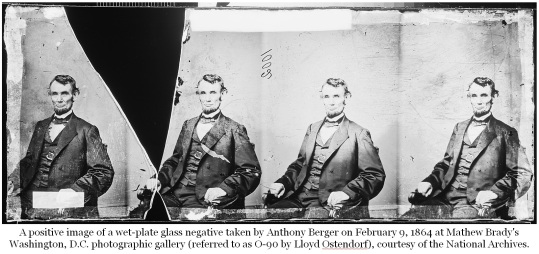

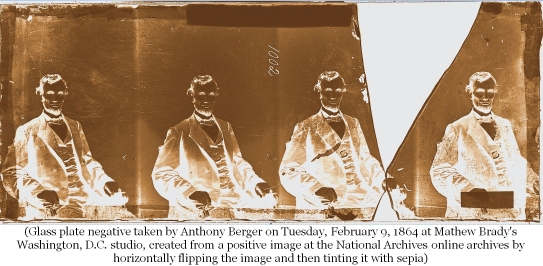

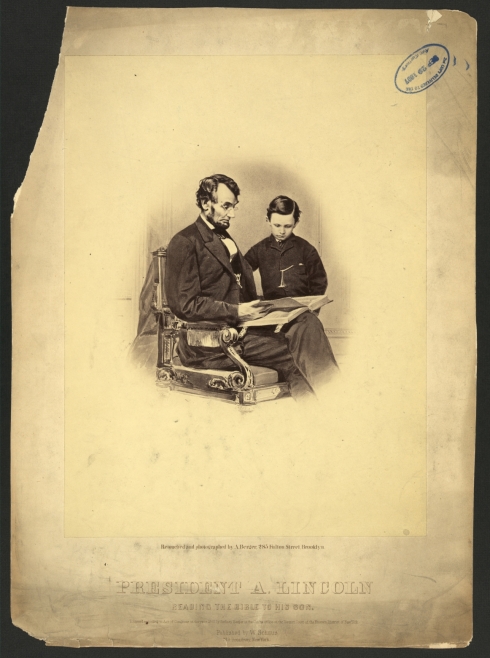

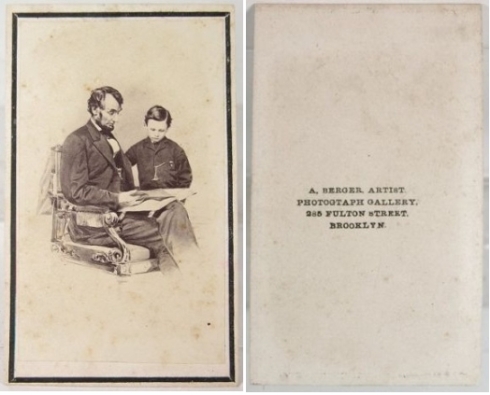

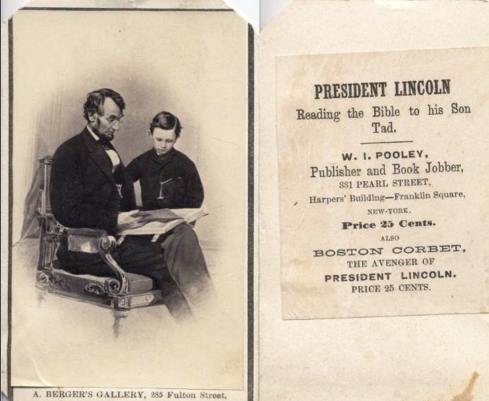

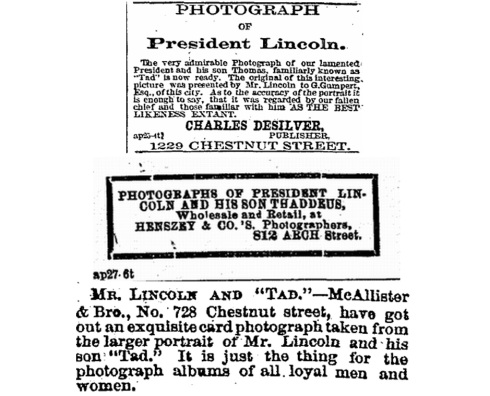

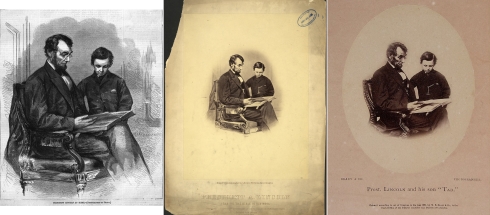

- Whose studio photographs of President Abraham Lincoln have graced both the U.S. penny and the $5 bill?

- Who took more known photographs of Lincoln other than a former colleague?

- Who photographed Lincoln to obtain studies used for a painting that hangs in the U.S. Congress?

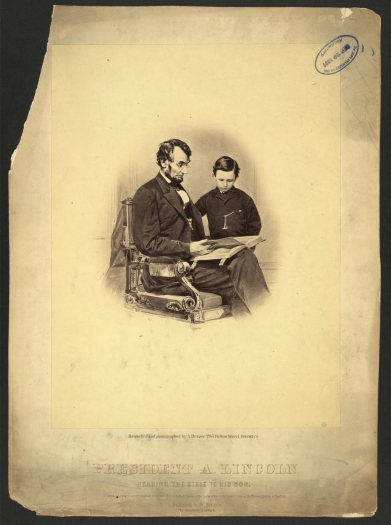

- Who photographed Lincoln in the White House where he allegedly fell prey to a prank pulled by Lincoln’s son Tad?

- Who was in Gettysburg on two separate occasions in 1863 taking photographs with David Woodbury?

It is fair to say that Americans who hold themselves out even as average students of American history are sure to recognize the name “Mathew Brady” as well as one or more iconic photographs produced under his nameplate. For many, “Brady” is the only recognizable name within the genre of mid-to-late 19th century photography. So if you answered “Brady” in response to the five bulleted questions above, count yourself among those with a failing grade and chalk up your misguided response to the fact that the vast majority of real “Brady” Civil War-era photographs, although a product of Mathew Brady’s creative genius and visionary thinking, were taken and developed by men who worked for him. As noted by a journalist in 1851, a full decade before the outbreak of the American Civil War, the New York City daguerrean artist:

“M.B. Brady, of 205 and 207 Broadway, corner of Fulton, has, however, after all, the largest and most fashionable establishment in the city. His enterprise is proverbial, and his gallery of the members of Congress, noted military, naval, and civil officers, perhaps cannot be equaled. Brady is not an operator himself, a failing eyesight precluding the possibility of his using the camera with any certainty, but he is an excellent artist, nevertheless — understands his business so perfectly, and gathers around him the first talent to be found.”[1]

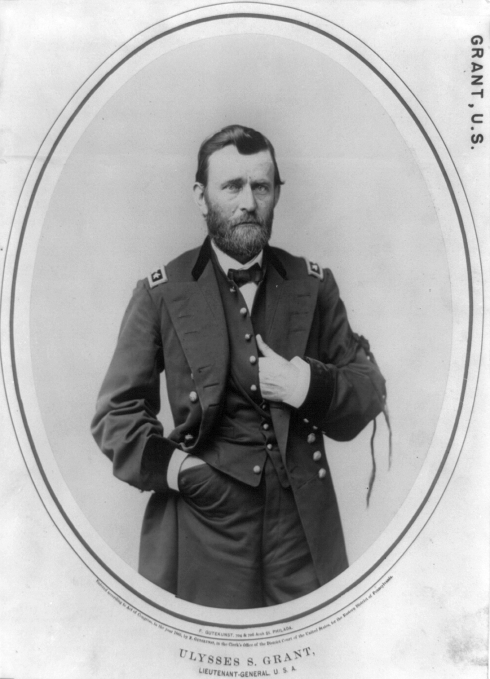

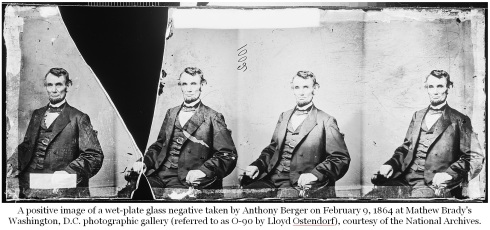

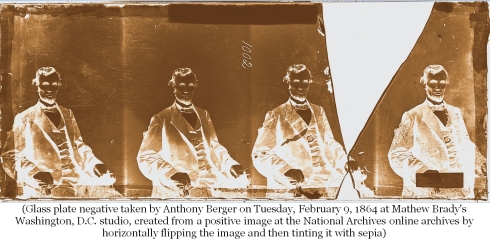

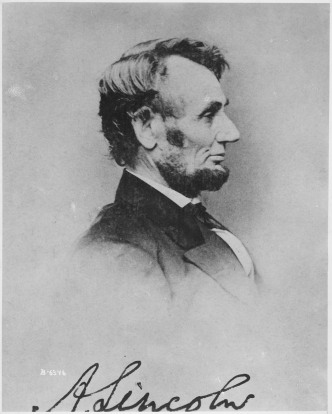

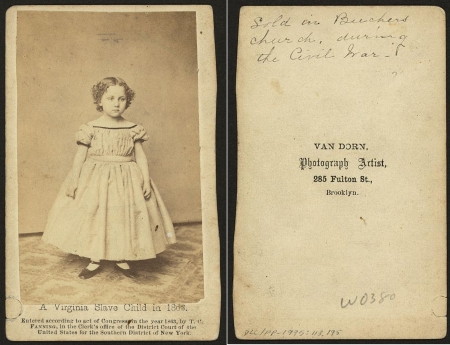

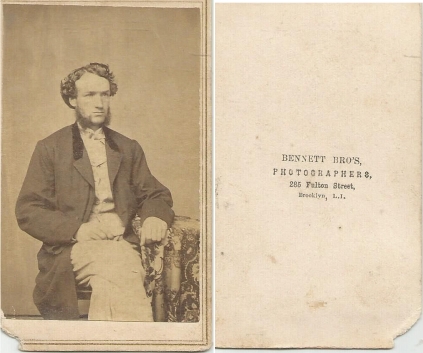

Roy Meredith, the author of the book Mr. Lincoln’s Camera Man, Mathew B. Brady (1946), asserts that although Mathew Brady left “the routine work of the gallery to his operators” throughout the Civil War and for several years thereafter, his prestige demanded that he personally handle “the most prominent of his sitters, and any celebrity who wanted a ‘Brady Photograph,’ naturally expected to be photographed by him and not by one of his operators.”[2] Providing personal attention to his most prestigious sitters in either his New York or Washington studios might have been a frequent Brady rule, but it was not without exceptions — even when President Lincoln walked through his studio door for a sitting. That is why one of the men of “first talent” who toiled behind the camera for Brady — ANTHONY BERGER — is the correct answer to all five of the questions posed above. Yet, virtually nothing biographical has been published about Mr. Berger. He is for all intents and purposes a veritable historical man of mystery. He isn’t even listed as a notable person at a Wikipedia site dedicated to his surname. James D. Horan, in Mathew Brady: A Historian with a Camera (1953), writes that in 1858:

“The eyesight of the prince of photographers was fading worse than ever. The long nights in the darkroom were extracting their toll. The lenses of his spectacles were now blue and even thicker. [Mathew B.] Brady could still be found behind the camera, but on rare occasions. He was still attracting the great men of America and the world to his busy galleries in New York … but other men were now doing most of the actual photography work. One was an Englishman named A. Berger — or Burger.”

Mr. Horan speculates that Anthony Berger was from England because the name “A. Berger” appears in London photography stories reprinted in the American publication Humphrey’s Journal. Noting that one piece[3] mentions that “A. Berger” was “on his way to New York,” Mr. Horan extrapolates that he probably is the same fellow who eventually ended up in Brady’s New York studio. Efforts, thus far, to locate “A. Berger” within Humphrey’s Journal have proven unsuccessful. Nevertheless, while digging for those references it came to light that several authors of letters and articles published or republished in that journal maintained their anonymity under the cloak of fictitious names such as “A. Subscriber,” “A. Stranger,” “A. Victim,” “A. Fault-Finder,” etc., suggesting that “A. Berger” could have been “A. Pseudonym.” Because Anthony Berger eventually worked for Mathew Brady and New York City is where Brady originally based his operations, the island of Manhattan is the most logical place to begin any search for Anthony Berger in America. The first references in a New York City Directory to a promising candidate for Anthony Berger appear on page 297 of Wilson’s Business Directory for New York City, published in 1855, under an occupational listing for “Painters, Landscape:”

“Berger, Anton, 251 Bowery”

and in the 1856 Trow’s New York City Directory, published in 1855 for the period of May 1855 to May 1856:

“Berger, Anton, artist[4], 359 Broadway, h 251 Bowery”[5]

Armed with the knowledge that Mathew Brady’s establishment was then listed at 205 and 359 Broadway Avenue, the Trow’s New York City Directory entry establishes that Anthony Berger (aka “Anton Berger”) was working for Mathew Brady in New York by sometime in 1855. The 359 Broadway location, described as “the showplace of the city’s [photographic] galleries,”[6] opened in 1853 and covered several floors atop Thompson’s saloon: “gazing down at the luxurious rooms from the frames of gold and rosewood are the kings, statesmen, emperors, and American leaders, living and dead … [The rooms have] the very best equipment. There is nothing in Brady’s apparatus of second quality … [it is] a prince of a gallery.”[7] By comparing his first five appearances in Trow’s New York City Directory with the last four, we discover that Anthony Berger’s given name was “Anton” which, with the passage of five years, morphed into the less Germanic sounding “Anthony”:

1855-1856: Berger, Anton, artist, 359 Broadway, h 251 Bowery

1856-1857: Berger, Anton, artist, 359 Broadway, h 251 Bowery

1857-1858: Berger, Andon [presumably a typo], painter, h 155 Forsyth

1858-1859: Berger, Anton, artist, h 55 W. 18th

1859-1860: Berger, Anton, artist, h 55 W. 18th

1860-1861: Berger, Anthony, artist, B’way c Tenth [8], h 55 W. 18th

1861-1862: Berger, Anthony, artist, h 55 W. 18th

1862-1863: Berger, Anthony, artist, 806 B’way, h 55 W. 18th [9]

1863-1864: Berger, Anthony, artist, h 55 W. 18th

Miss Josephine Cobb, former director of the Still Picture Branch of the National Archives, notes that “ANTON BERGER” was one of the artists employed by Brady to finish studio camera portraits “in oil [paint] on canvas or paper” which were “beautifully framed in gold” and sold for $750 a piece to wealthy clients. Essentially, they were oil paintings created by projecting the photographic image from a large glass plate negative onto paper or canvas, thereupon outlining the person’s face and any distinguishable features, and then finishing the imperial piece with oil paint. Other artists such as George Story and Henry Ulke, like Berger, performed the same services early in their professional photography careers. See Congressional Record – Appendix, March 11, 1965. Consequently, one of the skill sets either learned or further refined by Anton/Anthony Berger during his years of service with Brady included portrait oil painting, explaining his occupational listing as a “painter” in the 1857-1858 Trow’s New York City Directory. The beginning of Berger’s tenure with Brady coincided with Brady’s migration away from daguerreotypes to wet-plate collodion photography, the speed of which surely accelerated upon the arrival of Alexander Gardner at Brady’s New York studio in 1856.

The absence of anyone appearing in the New York City directories predating 1855-1856 with both the correct name and occupation of “artist,” “photographer,” “daguerreotypist,” “painter,” or a similar occupation, is evidence that Anthony Berger was not working or perhaps even living in New York City prior to 1855. This draws some support from a May 20, 1861 naturalization certificate issued by a New York Court of Common Pleas for “Anthony Berger” who then resided at 55. W. 18th Street, New York City, matching his home address in that year’s city directory. This naturalization record reveals that Anthony Berger the “artist” was from Germany — answering at least one question about his origins. The naturalization laws then in effect required a minimum of five years continuous residence in the United States (also, within that time period, two years had to pass between one’s initial declaration and later filing of a petition for citizenship) before citizenship could be attained. It was not unusual even for diligent aliens who immediately declared and petitioned for citizenship to experience delays in the processing of their petitions before finally being granted their citizenship after the five year period expired. A further search of the records also turned up Anthony Berger’s filing of a Declaration of Intention to Become a Citizen with the N.Y. Court of Common Pleas on December 13, 1854. In that document he renounced “all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, Potentate, State or Sovereignty whatever, and particularly to the Free City of Frankfurt.” So if the former Frankfurt, Germany resident moved as swiftly as possible to gain citizenship from his local New York County Court of Common Pleas, he arrived in America sometime in 1854. Anton/Anthony Berger was among the approximately one million Germans who left their homeland for America between 1850 and 1860 because of economic. political, regulatory, and military hardships. To gain an insight into the catalyst behind this German migration, I highly recommend reading The Last of the Blacksmiths (2014) by Claire Gebben. At least for the time being, what specifically drove Anthony Berger to come to America remains a time shrouded mystery. (To be continued) By Craig Heberton IV, published February 21, 2014

(Part II)

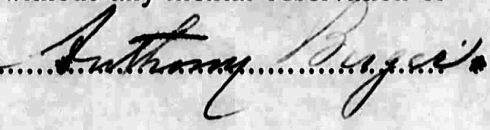

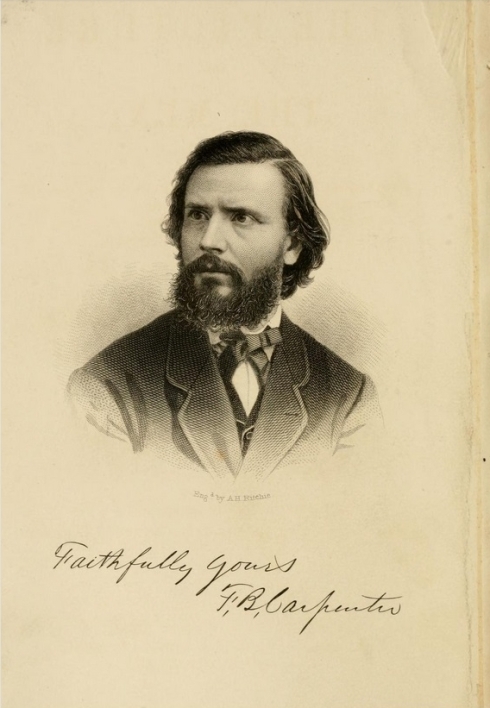

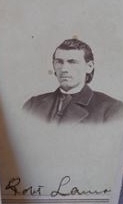

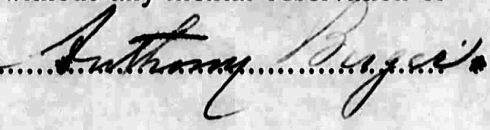

Anthony Berger’s naturalization record contains the necessary clues to determine when and where he was born as well as other significant biographical information. On June 12, 1897, an “Anthony Berger” was issued a United States Passport. Within his application, Mr. Berger indicated that he was naturalized as a U.S. citizen on the 20th of May 1861 and listed his occupation as “artist.” That information clinches any debate, establishing him as the correct Anthony Berger. See The National Archives, Passport Applications, 1795 – 1905, Roll 0490, Volume 851, Year 1897, in Fold3 (2008). Berger’s signature on his Oath of Allegiance submitted with his passport application follows:  This passport application reveals that Anthony Berger was born on February 9 (or 18), 1832 at “the free city of Frankfort on the Main,” Germany (aka Frankfurt am Main in the state of Hesse, now known simply as Frankfurt); he emigrated to the United States on board a ship from London on about February 8, 1854; his wife — Albertine — was born at Bockenheim, Germany (now a city district west of central Frankfurt) on March 26, 1831; he lived continuously for 43 years in the United States; as of 1897 he lived in New York City; and he intended to return with his wife to the United States “after a visit to Europe.” He was described as 65 years of age, a little under 5 feet 8 inches tall, gray eyed, possessed of a “full-round” nose and a “small pointed” chin, with a healthy complexion “inclined to be florid,” and “light brown” hair. Knowing that Anthony Berger arrived in America from London either a day before or a few days following his 22nd birthday — two different birth dates appear on different pages of his application papers — revives the possibility that he spent time in England, as suggested by Mr. Horan, where he might have been exposed to the photographic arts. But for now his life in Europe and possible training there as an oil painter, sketcher, water colorist, and/or photographer before coming to the U.S., is nothing more than a blank canvas. The only clue found to date — his listing as a landscape painter in the 1855 Wilson’s Business Directory for New York City — strongly suggests that he was formally trained in landscape oil painting or water coloring somewhere in Europe prior to his arrival in New York City.

This passport application reveals that Anthony Berger was born on February 9 (or 18), 1832 at “the free city of Frankfort on the Main,” Germany (aka Frankfurt am Main in the state of Hesse, now known simply as Frankfurt); he emigrated to the United States on board a ship from London on about February 8, 1854; his wife — Albertine — was born at Bockenheim, Germany (now a city district west of central Frankfurt) on March 26, 1831; he lived continuously for 43 years in the United States; as of 1897 he lived in New York City; and he intended to return with his wife to the United States “after a visit to Europe.” He was described as 65 years of age, a little under 5 feet 8 inches tall, gray eyed, possessed of a “full-round” nose and a “small pointed” chin, with a healthy complexion “inclined to be florid,” and “light brown” hair. Knowing that Anthony Berger arrived in America from London either a day before or a few days following his 22nd birthday — two different birth dates appear on different pages of his application papers — revives the possibility that he spent time in England, as suggested by Mr. Horan, where he might have been exposed to the photographic arts. But for now his life in Europe and possible training there as an oil painter, sketcher, water colorist, and/or photographer before coming to the U.S., is nothing more than a blank canvas. The only clue found to date — his listing as a landscape painter in the 1855 Wilson’s Business Directory for New York City — strongly suggests that he was formally trained in landscape oil painting or water coloring somewhere in Europe prior to his arrival in New York City.

Can any more information about Anthony Berger be teased out of the 1855 New York State and 1860 Federal census returns? The relative ease by which Anthony Berger is identified in the annual Trow’s New York City directories, however, does not carry over in the quest to locate him in those two census returns. The 1855 New York Census lists a 23 year-old “Mr. Burger” living in the 10th Ward of Brooklyn with a wife (identified only as “Mrs. Burger”) and a one year-old boy named David. Mr. Burger’s given place of birth is Germany and occupation is “painter.” This Mr. Burger, whose estimated birth year is 1832, purportedly had resided in Brooklyn for five years and was still an alien. Mrs. Burger, also 23 years-old, had been a resident for 3 years. Although his age, alien status, and occupation, as well as his wife’s age, are evidence that he is Anthony Berger the artist, other evidence suggests to the contrary. For example, Anthony Berger the artist listed his home address as 251 Bowery, New York City in the 1855-1856 and 1856-1857 New York City Directories. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that after the taking of the state census in July of 1855, “Mr. Burger the painter,” having previously secured employment with Mathew Brady, moved his residence from Brooklyn to 251 Bowery, New York City in order to be closer to his workplace. This could have occurred some time before the Trow’s directory canvassers showed up at his new doorstep. By listing them merely as Mr. & Mrs. Burger, the census taker betrayed that the information he received likely was communicated to him by someone else on behalf of the Burgers possibly because one or both of the couple’s English speaking skills were poor. If the indicated time that Mr. & Mrs. Burger lived in Brooklyn was misunderstood, improperly translated, or erroneously given, Anthony Berger the artist may have lived first in Brooklyn for as much as a year and a half and fathered a son there.

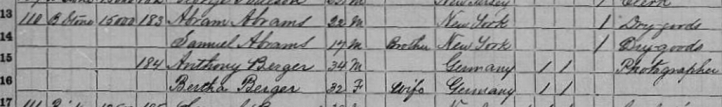

The index for the 1860 Federal Census reveals only one Anthony (or Anton) Berger (or Burger) in the greater New York City area — an “Anthony Berger” in the 9th Ward of New York City. He is described as a 32 year-old German-born locksmith living with his wife Dora, aged 31, and son Louis, aged 5. This is not the correct Anthony Berger, as he also is listed in the 1855 New York State Census as residing in the 9th Ward of New York City and described as a “machinist” born in Germany in about 1826 who had lived in the city for 7 years with his wife Doretha — evidence that he emigrated to America no later than 1848. In the 1855-1856 Trow’s New York City Directory he is identified as a “smith” living at 237 Bleecker St. (which was then within the 9th Ward of NYC); in numerous subsequent city directories he is listed as a “locksmith.” A faulty or nonexistent index listing in the 1860 Federal Census may prevent us from ever finding the correct Anthony Berger.

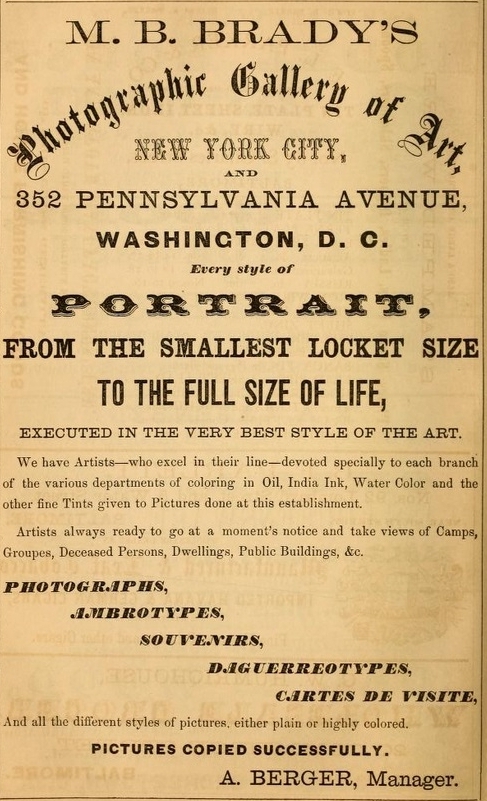

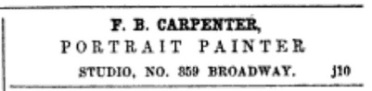

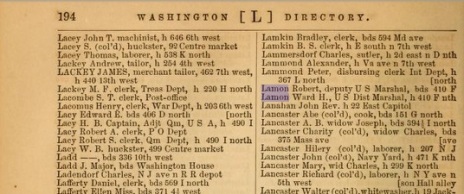

The day after his naturalization as an American citizen, Anthony Berger applied for a U.S. Passport on May 21, 1861. That application notes that he was born in Frankfort on February 18, 1832 and his vital statistics were 5 foot and 7 and one-half inches tall, grey eyes, full nose, small pointed chin, light brown hair, fair complexion, and a face characterized as “nothing vile looking.” Theo Murray Squires, his notary and agent, placed Mr. Berger’s papers in an envelope addressed to Hon. Wm. H. Seward, Sec. of State, and requested the return of “the same with all economical speed you will oblige.” It is not clear whether the passport was issued but it likely was denied by the State Department due to the outbreak of the Civil War during the prior month. Berger probably waited until after he was naturalized to seek a passport because citizens stood a better chance of being granted one on a rush basis and need not fear being readmitted upon their return. Squires’ cover letter which requested expedited handling, coupled with an indication in the application that Mrs. Berger would accompany her husband to Europe, suggest that the Bergers were in a hurry to return to Germany because of the outbreak of war or to address a pressing event such as a serious family illness or the death of a loved one. After working approximately 9 years in New York City for Mathew Brady, the next rite of passage in Anthony Berger’s professional career demonstrates that by 1863 he had earned Brady’s deep respect for his talents both as an artist as well as an office manager. We pick up his trail again in the 1863-1864 Boyd’s Washington [D.C.] and Georgetown Directory at “Brady’s photographic gallery, 352 Penn ave.” An advertisement in that directory identifies him as the gallery’s manager (see below):

We also know that Anthony Berger traveled to Gettysburg with David Woodbury, another Brady assistant, a few days after the battle ended there on July 3, 1863. The evidence points to the conclusion that Berger and Woodbury reached Gettysburg from Washington, D.C. and Mathew Brady later joined them from New York City by July 15. Alexander Gardner sent an undated telegram sometime shortly after July 9, 1863 addressed to Timothy O’Sullivan “[at] Head Quarters, Army of the Potomac” — anticipating that O’Sullivan had caught up with Meade’s forces as they cautiously “pursued” Lee’s army after the Battle of Gettysburg. Like Gardner, O’Sullivan was a highly skilled cameraman and a former Brady employee. Gardner’s telegram states:

“I have just got back [presumably to Washington, D.C.] from Gettysburg … [David] Woodbury & [Anthony] Berger were there. If they come your length I hope you will give them every attention. tell Jim [Gibson] that McGraw is dead. I will write.” See William A. Frassanito’s seminal book Early Photography at Gettysburg (1995) at pp. 22-25.

Robert Wilson, author of Mathew Brady: Portraits of a Nation (2013), at p. 157, speculates that Gardner’s message reflects either his desire to maintain good relations with Berger and Woodbury, with an eye towards possibly recruiting them away from Brady, or a simple admonition to “keep an eye on the competition” should they join the Army of the Potomac to take pictures of the aftermath of what President Lincoln hoped would prove to be a decisive and war-ending Union victory — a result which didn’t happen. Although the latter inference makes the most sense, Gardner likely wanted O’Sullivan to try to achieve both objectives given the fact that Woodbury and Berger were then among Brady’s most talented men whom Gardner knew well from his many years working for Brady.

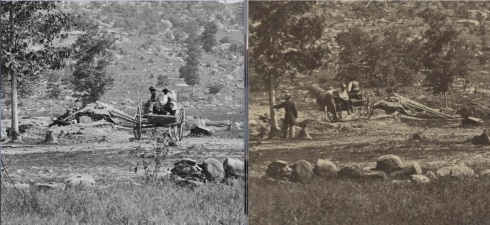

We don’t know which “Brady” photographic plates were prepared, taken, or developed by Anthony Berger in July of 1863 at Gettysburg. But it is very possible that some of the most famous Brady Gettysburg images were Berger’s creations or the product of his handiwork:

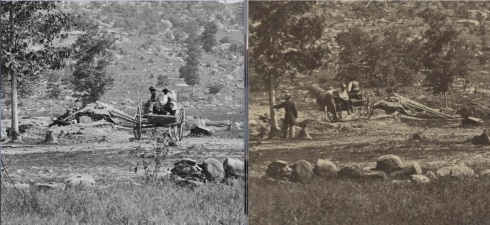

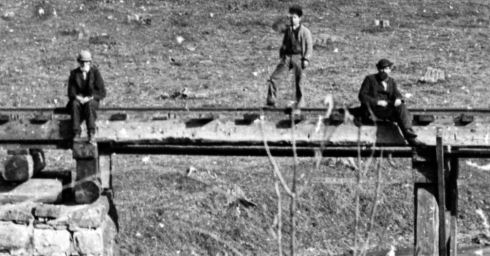

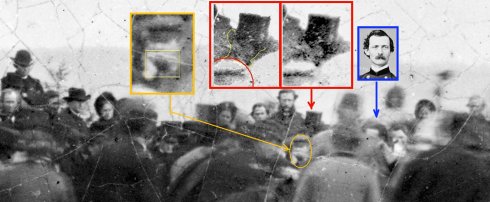

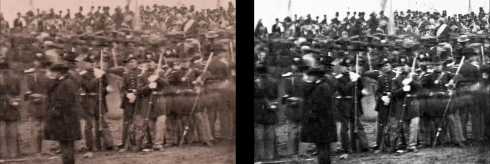

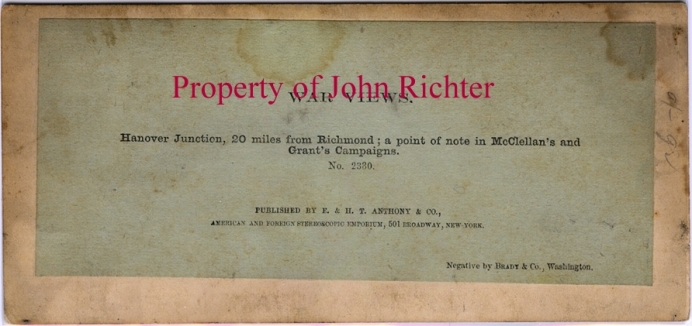

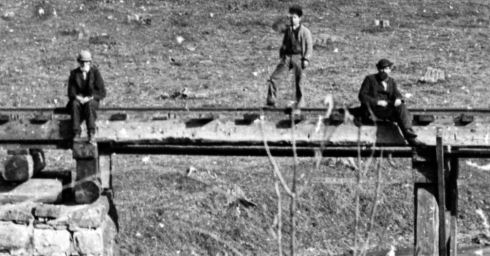

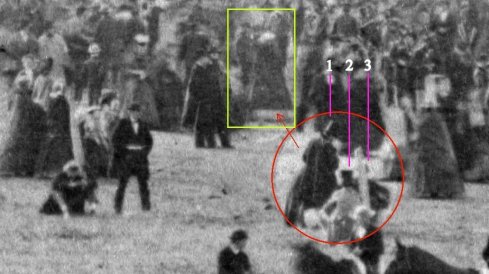

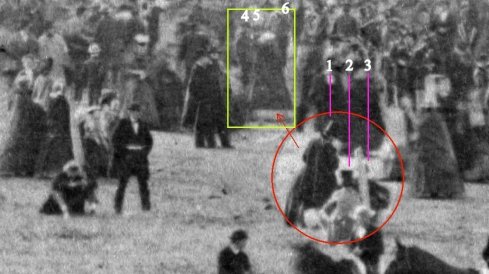

“Because Brady, unlike Gardner, did not credit each photograph with a name of a photographer, it is virtually impossible to identify his assistant cameraman … It is fairly certain, however, that none of the [Gettysburg] views was personally taken by Brady … [rendering] the famous photographer’s role at Gettysburg … essentially that of a supervisor. Of some significance is the varying presence of at least one of three men in most of the Brady views. The three consist of Brady and two men who were no doubt his assistants, one wearing a dark vest, the other a white shirt occasionally covered by a white duster. A view taken near Little Round Top [see detail below, right] shows all three men together, which indicates the presence of another companion operating the camera. Whether or not this third assistant took most or all of the photographs cannot be determined.” William A. Frassanito, Gettysburg: A Journey in Time (1975), at p. 38.

Assuming that Mr. Frassanito is correct, two of Brady’s assistants (rather than local guides) are visible in some of his Gettysburg views — sometimes solo, sometimes together, and occasionally (one or both) with Brady. He also points out that when all three men appear together, it is revealed that a third Brady assistant took the view. Robert Wilson speculates that this third assistant accompanied Brady from New York. For some inexplicable reason, the third assistant never seems to appear in any of the views, unless he is the man pictured in detail from a photograph taken at the Bryan House in Gettysburg (discussed below). If only Berger, Woodbury, and the third assistant were with Brady in Gettysburg AND the two men pictured were, in fact, Brady photographers, then either Berger or Woodbury MUST be visible in some of those views. And if the assistant who took the photographs showing both of the other two Brady assistants was the unidentified assistant from New York, then BOTH Berger and Woodbury must be visible in those views. With this in mind, let’s explore specific details within some of Brady’s Gettysburg photographs.

The cropped images, below, are from two different but similar Brady views taken in the “Valley of Death” near the base of Little Round Top (courtesy of the Library of Congress). They appear to have been shot consecutively.

Narrower focused image detail is marked below to identify the presence of Brady and his two assistants. In both instances, Mathew Brady is the man under a blue arrow.

In the likely first-in-time image on the left, above, Brady sits in a horse-drawn cart; in the latter, taken from a slightly different perspective resulting from moving the camera a distance to the right, he got out of the cart after it moved away from the camera and braced himself with his left hand extended straight out to the trunk of a tree in a contemplative pose. He was replaced in the cart by the man seen in repose on the ground in the prior exposure near where the cart was then halted. That person, whom Mr. Frassanito labels as “no doubt” a Brady assistant — wore a light-colored shirt and a nice looking pair of high boots. He is hatless and boxed in red within detail, above, in the left marked image and beneath the red arrow in the right image. The man whom Mr. Frassanito describes as the Brady assistant “wearing a dark vest” is visible in both views under a yellow arrow in the marked detail, above.

It is not clear whether Brady wanted the assistant in the light-colored shirt to be imperceptible in the first picture (which he nearly is) or if he intended that this man would be both discernible to the viewer and interpreted as a dead soldier. If Brady’s goal was the latter, he failed miserably because that man qualifies as a “Where’s Waldo?” contestant by blending in with the rocks and fence posts flanking him. The best clue alerting us to his presence is the fact that Brady and his cart companion are seen in active poses facing towards and staring directly at “the corpse” as if they just had made the startling discovery of his dead body.

To better study this man’s appearance, see the zoomed detail, below:

To better study this man’s appearance, see the zoomed detail, below:

Unlike Alexander Gardner, Brady posed himself in several of his sweeping Gettysburg views either to create enhanced stereoscopic visual perspective, add context or emotion to the scene, and/or simply to insert himself into the pictorial record of history he was creating. Robert Wilson notes that Brady’s appearance in scenes also served as “proof” that the image was an honest-to-goodness Brady created photo. This achieved at least two goals. First, it served to foil competitors inclined to try to profit from Brady images by photographing them and then passing off copies of slightly retouched prints as their own original work. Second, it allowed the viewer, in a sense, to be escorted to that particular place in the company of the famous “Brady of Broadway” — an effect greatly enhanced when the view was shot in stereoscopic 3-D. Perhaps that is among the reasons why more than two-thirds of Brady’s output at Gettysburg was stereo views. Stereo images visually transported viewers to famous battlefield locations described by newspaper accounts in great detail and certainly aroused reactions such as — “so THAT is how it would have looked had I walked the grounds in the company of the great war photographer Brady!”

Unlike Alexander Gardner, Brady posed himself in several of his sweeping Gettysburg views either to create enhanced stereoscopic visual perspective, add context or emotion to the scene, and/or simply to insert himself into the pictorial record of history he was creating. Robert Wilson notes that Brady’s appearance in scenes also served as “proof” that the image was an honest-to-goodness Brady created photo. This achieved at least two goals. First, it served to foil competitors inclined to try to profit from Brady images by photographing them and then passing off copies of slightly retouched prints as their own original work. Second, it allowed the viewer, in a sense, to be escorted to that particular place in the company of the famous “Brady of Broadway” — an effect greatly enhanced when the view was shot in stereoscopic 3-D. Perhaps that is among the reasons why more than two-thirds of Brady’s output at Gettysburg was stereo views. Stereo images visually transported viewers to famous battlefield locations described by newspaper accounts in great detail and certainly aroused reactions such as — “so THAT is how it would have looked had I walked the grounds in the company of the great war photographer Brady!”

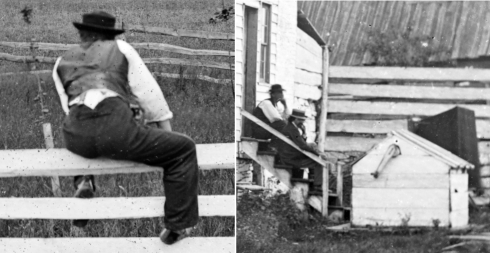

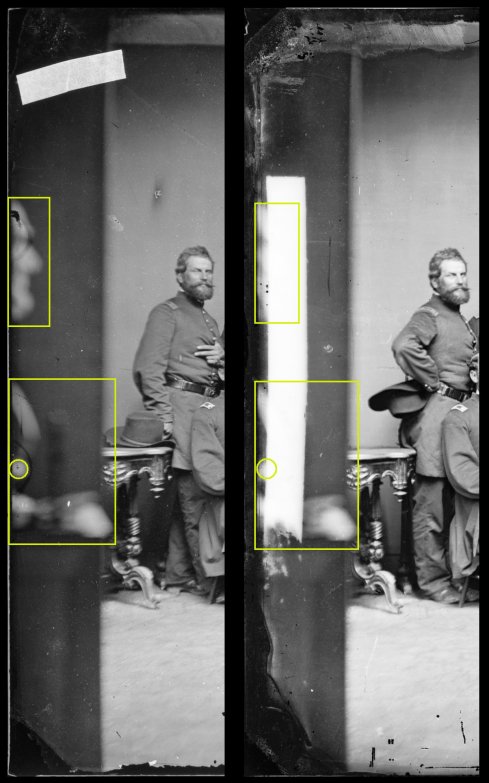

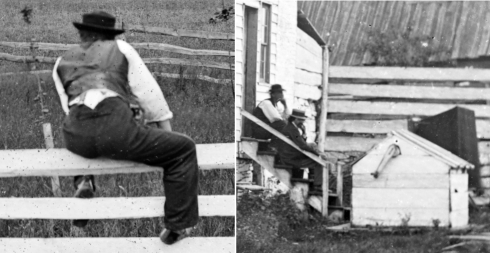

The Brady assistant wearing the dark vest and dark hat appears in several other Gettysburg views. See below, for example, detail from two images taken at Gettysburg’s Lutheran Theological Seminary (left) and John Burns’ home (right), courtesy of the Library of Congress. Support for the conclusion that he was a Brady photographer is at its strongest in the photo in which he is seated with Mathew Brady on the back steps of John Burn’s home near a portable darkroom on a tripod — presumably the darkroom to which that image’s photographic plate was rushed for development immediately after it was exposed. John Richter was the first to describe these details in 2004.

That man also is visible in an image seated alone at John Burns’ house (see image detail below left, courtesy of the National Archives) and with the man in the light-colored shirt and duster on Culp’s Hill in a Brady War Views stereo card captioned on the verso “Breastworks on the Left Wing, Battle of Gettysburgh, No. 2424” (in detail, below right, courtesy of John Richter). To read about a young researcher’s modern day visit to the exact spot where the Culp’s Hill stereo view was taken and to see her recreation of the Brady view, visit http://civilwarsallie.blogspot.com/2009/11/csi-gettysburg-part-1.html:

That man also is visible in an image seated alone at John Burns’ house (see image detail below left, courtesy of the National Archives) and with the man in the light-colored shirt and duster on Culp’s Hill in a Brady War Views stereo card captioned on the verso “Breastworks on the Left Wing, Battle of Gettysburgh, No. 2424” (in detail, below right, courtesy of John Richter). To read about a young researcher’s modern day visit to the exact spot where the Culp’s Hill stereo view was taken and to see her recreation of the Brady view, visit http://civilwarsallie.blogspot.com/2009/11/csi-gettysburg-part-1.html:

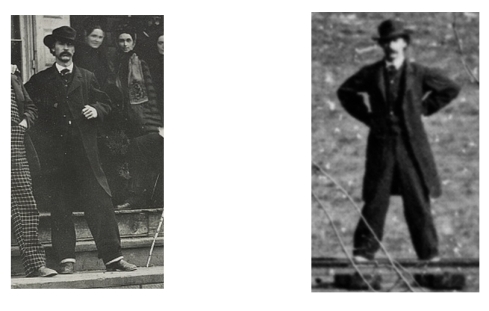

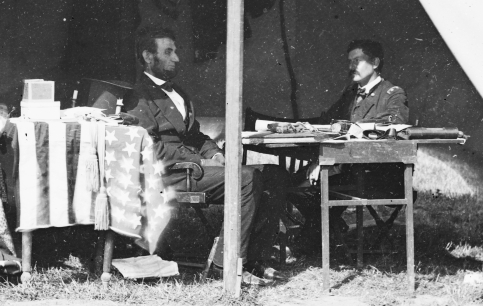

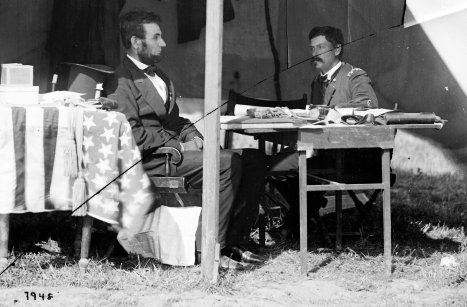

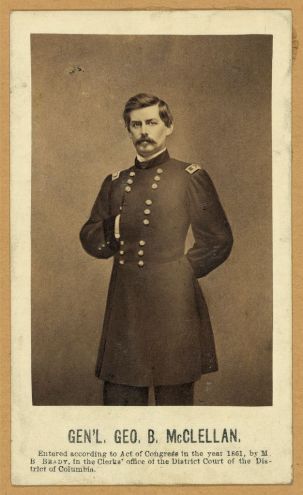

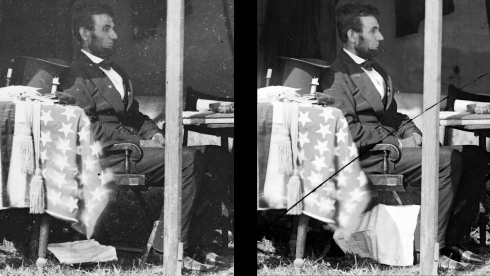

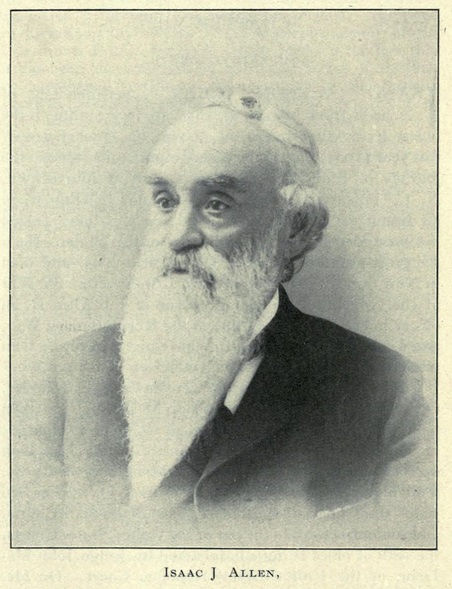

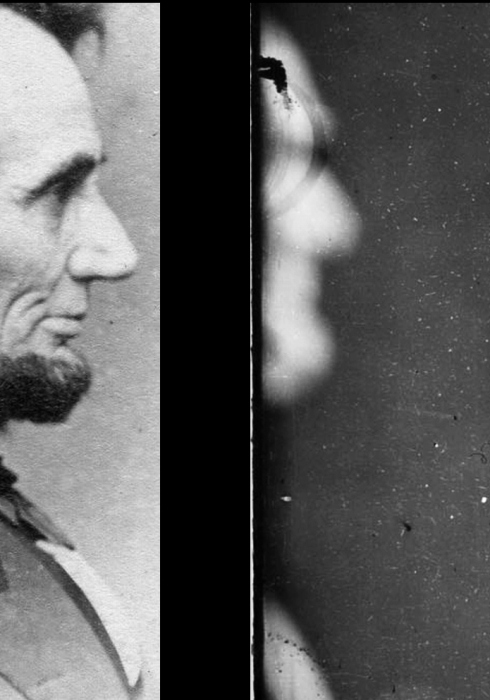

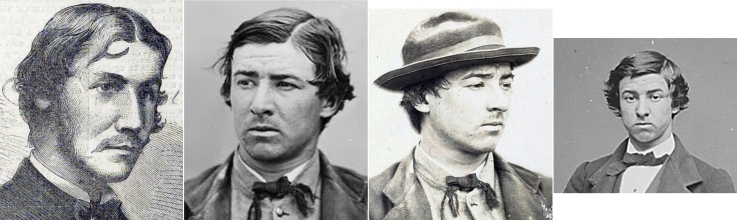

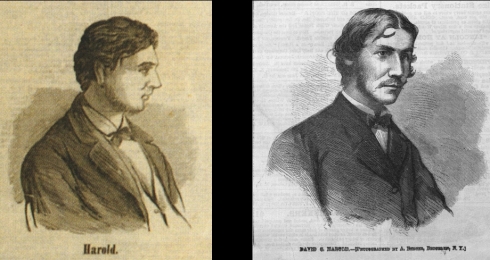

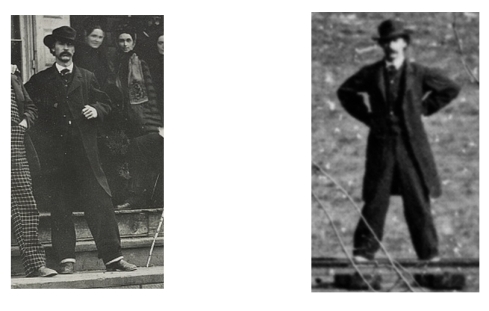

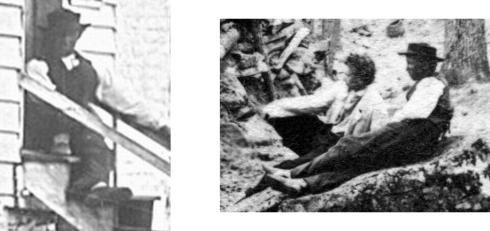

Compare the images of the man wearing the dark vest with detail (below) from a photo depicting a heavily bearded David Woodbury (left) in the field near Petersburg, VA in 1864, courtesy of the Library of Congress, and another image of Woodbury from an October 1862 photo (right). It is difficult to discern whether the dark vest man was lightly bearded or completely clean-shaven. Regardless, does his long nose suggest that he could be David Woodbury? Unfortunately, the poor quality of the detail within the Gettysburg images does not allow for a satisfactory comparison, leaving open the possibility that the dark vest man could be someone else, perhaps even Anthony Berger.

Compare the images of the man wearing the dark vest with detail (below) from a photo depicting a heavily bearded David Woodbury (left) in the field near Petersburg, VA in 1864, courtesy of the Library of Congress, and another image of Woodbury from an October 1862 photo (right). It is difficult to discern whether the dark vest man was lightly bearded or completely clean-shaven. Regardless, does his long nose suggest that he could be David Woodbury? Unfortunately, the poor quality of the detail within the Gettysburg images does not allow for a satisfactory comparison, leaving open the possibility that the dark vest man could be someone else, perhaps even Anthony Berger.

Alternatively, if the dark vest man traveled from New York with Brady, he might be a different long-nosed Brady assistant — Edward T. Whitney — seen in detail from an October 1862 photo, below right, next to zoomed detail showing the dark vest man, below left:

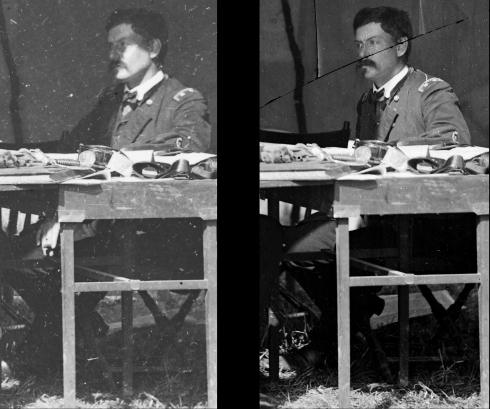

Whitney, however, never mentioned being in Gettysburg in July of 1863 in a short published article of his reminiscences of working with David Woodbury in the field on behalf of Brady during the Civil War. A side-by-side comparison of the E.T. Whitney image (right, below) with another from Blackburn’s Ford, near Manassas, VA in about August of 1862, probably also reveals Whitney (courtesy of the Library of Congress):

Whitney, however, never mentioned being in Gettysburg in July of 1863 in a short published article of his reminiscences of working with David Woodbury in the field on behalf of Brady during the Civil War. A side-by-side comparison of the E.T. Whitney image (right, below) with another from Blackburn’s Ford, near Manassas, VA in about August of 1862, probably also reveals Whitney (courtesy of the Library of Congress):

A striking feature of the 1864 photo of David Woodbury is that his white duster and shirt collar resemble the same seen on the man described by Mr. Frassanito in the Brady Gettysburg views as wearing “a white shirt occasionally covered by a white duster.” Perhaps his shirt and boots do as well. That man is visible, without a duster, at the base of Little Round Top in the two photographs discussed above. He also is seen sporting a goatee in detail from several other Gettysburg views, including one taken in front of the Evergreen Cemetery gatehouse (below, left) and another on Culp’s Hill (below, right), courtesy of the Library of Congress. Surprisingly, his goatee in the image on the right appears longer than in the one on the left. Nevertheless, the boots, dark rolled cuff pants, white duster, and shirt collar indicate that he is the same man. Is he Anthony Berger, who was then 31 years old, or a 24 year-old David Woodbury?

This same man probably appears sans duster within detail of a view taken at the summit of Little Round Top , below left, and laying on the ground and presumably “playing dead” at Culp’s Hill, below right, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The positioning of his left arm and hand are used as illustrative tools in two other poignant Gettysburg photos. In the first, captioned “Scene of General Reynold’s Death” (below, left), he points as if directing Brady to the exact spot where Reynolds was struck dead. In another, he sits on a Little Round Top tree stump shading his eyes as he seemingly contemplates the acts of heroism performed there a few days earlier (below, right). The detail below is courtesy of the Library of Congress.

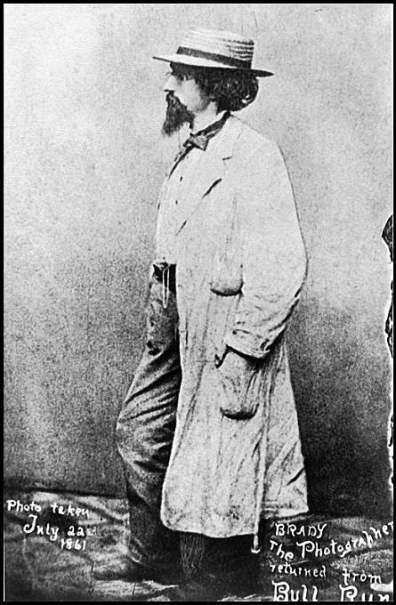

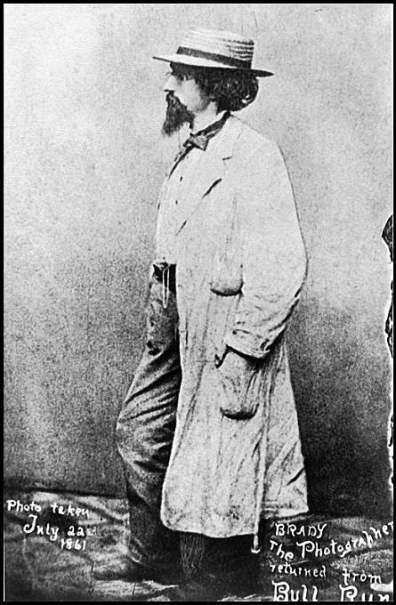

The manner of dress of this man is reminiscent of the get-up sported by Mathew Brady (below, courtesy of the Library of Congress) in a pose he purportedly assumed on July 22, 1861 after returning to his Washington studio following the First Battle of Bull Run. Perhaps Anthony Berger, who by July of 1863 was the supervisor of Brady’s D.C. gallery (as discussed below), intentionally emulated his boss’ flair for wearing dashing garb in the field:

Some details in the 1864 photo of David Woodbury, mentioned above, suggest that he is the man with the goatee wearing a white duster. But that evidence is based less upon physical appearance and more upon clothing similarities which may be nothing more than a coincidence. Woodbury’s dark hair color doesn’t appear to match the lighter brown color of the man with the goatee. Moreover, the face of the goateed man with the duster standing in front of the Evergreen Cemetery gatehouse doesn’t look to be shaped like Woodbury’s or possessed of a similar nose, leaving open the possibility that he is Anthony Berger. Woodbury’s lengthy nose might appear on the face of the dark vested assistant, but that assistant is without the sort of significant beard seen on Woodbury in the 1862 and 1864 views, above. The image detail from the Gettysburg photos also doesn’t allow for an easy comparison between the two assistants and the description of Berger’s appearance in his 1897 passport application — a little under 5 feet 8 inches tall, gray eyed, possessed of a “full-round” nose and a “small pointed” chin, with a healthy complexion “inclined to be florid,” and “light brown” hair.

Therefore, it is a challenge to pronounce either of the two Gettysburg assistants as Anthony Berger. The white duster man’s lighter facial complexion suggests that he spent most of his time working indoors, perhaps in Brady’s New York studio or managing the D.C. gallery. This observation suggests that Berger is more likely the white duster assistant than the dark vested one. But Berger’s complexion which was described as “florid” in his passport application, better matches the ruddy facial appearance of the dark vest assistant. Before “chewing” on any other pieces of evidence in the quest to find Anthony Berger in the Gettysburg images, I direct the reader’s attention to a print of an October 1862 photo appearing in Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War (Hack Collection No. 2) at the Chrysler Museum of Art titled “Harper’s Ferry (Mathew Brady by pole).” See http://collection.chrysler.org/emuseum/view/objects/asitem/search$0040/1/title-asc?t:state:flow=bf7ed803-0120-4f17-b6d6-7d32749ad90c. The photo is attributed to David Woodbury and depicts a scene shot at Harper’s Ferry with Mathew Brady standing, a young boy gazing at Brady, a seated woman cradling a baby, a soldier on a railroad tie, and a dark vested man in a three-piece suit standing in profile. The latter man’s facial profile is similar to the dark vest assistant’s profile observed at Culp’s Hill. Likewise, his hat appears to be a match. Because we know that Woodbury and Berger worked together in the field on two separate occasions in 1863, including in one instance with Brady, it is likely that they worked together on other occasions as well. So if the dark vest assistant at Gettysburg appears with Brady in the Woodbury photo taken along the Potomac River at Harper’s Ferry in October 1862, then it constitutes evidence supporting the conclusion that Anthony Berger is the dark vest assistant at Gettysburg, the light-colored duster assistant is the unknown man who accompanied Brady from New York, and Woodbury never posed in any of the Gettysburg views.

Likewise, the dark vest man may well be the man wearing the identical hat with a similar facial profile seen in a Brady plate taken at City Point, VA (circa fall of 1864) in a photo from the National Archive’s collection titled “Hospital ambulance and corral near City Point, Va” (see detail, below). Because it is known that Brady’s assistants David Woodbury and Anthony Berger were in City Point off and on during that period of time, this may well constitute further support for the argument that the dark vest man could be Anthony Berger.

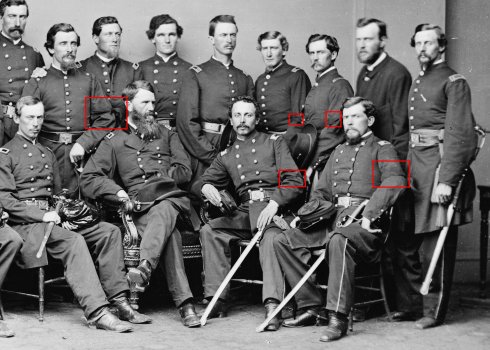

Over the course of the several days that Brady was in Gettysburg, his team recorded 36 known plates according to Bob Zeller. Brady placed himself in 9 of the views. The assistant with the dark vest appears in at least 6 of them. But the assistant with the light-colored shirt and duster (both on or off) is counted in a whopping 15 photographs. In as many as 4 of those views, it can be interpreted that the light-colored shirt assistant was posed laying on his back stretched out on the ground or leaning in a rigor-mortis induced position against an object on the ground in order to portray a dead soldier. When digitally zoomed in upon, the poses appear to the modern eye as lame attempts to mimic soldiers, let alone Confederate corpses (see three examples below, courtesy of the Library of Congress). But Brady must have envisioned that he would achieve the desired effect because the details of his “corpses” would not be readily apparent to his customers and, therefore, could not betray his staged recreations. I like to think of this in 1860’s terms as Brady exercising some “artistic license” in order to compose an emotionally compelling and potentially more commercially appealing scene. Landscape painters frequently did the same and do the same today.

Brady also must have adjudged this man to be possessed of the necessary young Rebel soldier “look” as well as dramatic and artistic flare, because he never posed the dark vest assistant as a dead man. One of the three photos taken at the Bryan/Brian House reveals that the carcass of a dead and partially mummified horse or mule rested nearby. The stench from that dead animal must have been significant, suggesting that the assistant in the light-colored shirt who posed in two of the Bryan House views only a few yards away from the decaying animal was the lowest person in the pecking order within Brady’s group.

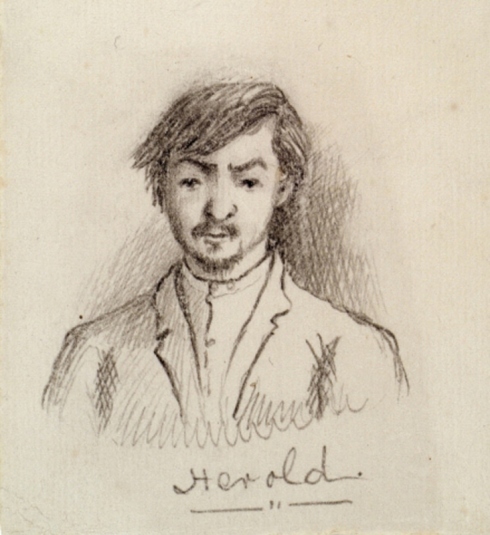

In only one of the Gettysburg views appears a man who is neither Mathew Brady nor dressed like either the dark vest assistant or the light-colored shirt/white duster assistant. Even though he wears a soldier’s jacket — which probably was scavenged from the battlefield — it is quite possible that he is the so-called third assistant not otherwise visible in any other Brady Gettysburg views. He can be seen posing in a single photographic view exposed at the Abraham Bryan/Brian House (which Brady and his men mistook for General Meade’s headquarters) along with the light-colored shirt assistant (detail below left, courtesy of the Library of Congress). Is he a Brady assistant dressed up to look like a soldier and, if so, is he the dark vest assistant wearing very different garb or the third assistant making a cameo appearance? He certainly may be Berger because his nose is “full [and] round,” his chin is “small [and] pointed,” and his forehead is “broad,” matching the description of Berger’s facial characteristics in his passport applications. Compare his face to the face of a man within detail of a photograph taken at City Point, VA which is attributed to Mathew Brady (courtesy of the National Archives), below right. They could well be the same man:

Despite the difficulty in conclusively identifying Anthony Berger in the “Brady” photographs taken at Gettysburg or pinpointing which images he created, it is clear that he had a substantial overall impact on Brady’s post-battle portfolio at Gettysburg. For starters, Bob Zeller notes that: “Before Brady arrived, Woodbury and Berger had plenty of time to scout … where fighting occurred in Gettysburg, and they were probably the ones who located and identified the area of fighting on the first day of the battle [as well as] Culp’s Hill, a prime location for photography. [Alexander] Gardner had missed both areas.” In addition to their work behind the camera, Berger & Woodbury would have contributed to the Gettysburg photographic results by preparing and developing glass plates. Development and “fixing” of the plates required a skilled hand and substantial darkroom experience in order to create a properly exposed image sporting both a depth of contrast and uniform clarity in scenes rich with many details.

If Anthony Berger is neither of the two apparent assistants in the Brady Gettysburg views, then it increases the likelihood that he stood behind the camera and exposed many of Brady’s iconic Gettysburg images. If, for example, he appears in only 6 of them as the dark vest assistant, it is likely that he exposed at least a few of the views. By waiting until the corpses and dead animals had been buried or removed from the battlefield, Brady, Berger and Woodbury missed the opportunity to photograph the obscene horrors of Gettysburg captured by Alexander Gardner’s team a few days earlier. Yet, while waiting for Brady, “Woodbury and Berger evidently made good use of their days in Gettysburg … familiarizing themselves with the town, the battlefield, and the reports of the battle … [gathering] local knowledge,” resulting in photographs adjudged by Robert Wilson to be “far superior to Gardner’s.” Mathew Brady: Portraits of a Nation, at 159. In the words of Bob Zeller, “Brady’s photographs exude their own style — not gritty and graphic, but expansive and contemplative. Many were sizable landscapes or panoramas with a strategically placed observer or two, sometimes Brady himself, to encourage the viewer of the photograph to form a personal vision of what the battle must have been like.” Whereas Gardner’s photographers were “the quintessential news reporters” who captured the horrors of the battlefield, [Brady, sporting the eye of a] portrait and landscape artist, produced with his assistants [scenes such as] ‘Three Rebel Prisoners'” (detail below, courtesy of the Library of Congress). Bob Zeller, The Blue and Gray in Black and White (2005), at p. 104.

Anthony Berger’s background as a landscape painter, first documented in a New York City directory in 1855, undoubtedly played a large role in Brady’s achievement in capturing expansive scenes of the Gettysburg battlefield, further bringing to life the exhaustively read newspaper accounts of the fighting at locations such as Culp’s Hill, Little Round Top, and even the very spot on Seminary Ridge where Major General John F. Reynolds [purportedly] had fallen. At the very least, Anthony Berger deserves substantial credit for Brady’s cumulative photographic output at Gettysburg.

The Enrollment Act, which went into effect on March 3, 1863, required nearly every able-bodied and mentally fit male citizen and immigrant seeking to be naturalized between the ages of 20 and 45 to enroll for possible military service. When Provost Marshal General James B. Fry and his assistants determined quotas for various draft districts in the respective states, lotteries were held to pick the names of the men to be conscripted for service. Thanks to this law, it can be ascertained that by the first of July in 1863, Anthony Berger may have been acting as Brady’s gallery manager in Washington in that he appears on a July 1, 1863 Consolidated List of Class I men subject to perform military service within the 3rd Sub-District of the District of Columbia :

| Resided |

Name |

Age |

Profession |

Marital |

Birthplace |

| 359 S St. |

Burger, Anthony |

33 |

Artist |

Married |

Germany |

He also appears in a July 25, 1863 Consolidated List for the 4th Sub-District of Washington City, under his business address, which identifies him as the Superintendent of Brady’s Gallery at 352 Pennsylvania Avenue:

| Resided |

Name |

Age |

Profession |

Marital |

Birthplace |

| 352 Pa. Ave |

Berger, Anthony |

33 |

Supt. Brady’s Gallery |

Married |

Germany |

David B. Woodbury’s November 23, 1863 letter to his sister — described in Craig Heberton’s “The Brady Bunch: The Case of the Missing Gettysburg Photos” — affirmatively states that Anthony Berger was managing Brady’s D.C. studio at that time. Because Anthony Berger is not listed either in the 1860 or 1862 Boyd’s Washington and Georgetown Directories but appears in the 1863-1864 Trow’s New York City Directory, it can be concluded that he neither was the gallery manager for nor was situated at Brady’s Washington, D.C. gallery any earlier than 1863. This nearly dovetails with Alexander Gardner’s tenure as the gallery manager of Brady’s D.C. studio which lasted either until Gardner traveled away from the studio for an extended period of time as a member of the U.S. Topographical Service for the Union Army in 1862 or whenever he formally left Brady’s employment which, according to D. Mark Katz, occurred sometime late in 1862 or early in 1863. For some unknown period of time after Gardner’s departure, James F. Gibson apparently managed Brady’s D.C. gallery until he was replaced by Berger. According to Don Nardo, “shortly after Gardner left, Gibson left Brady as well and went to work for Gardner.” Mathew Brady: The Camera is the Eye of History (2009), at p. 82.

What challenges might Anthony Berger have faced serving as the manager of Mathew Brady’s Photographic Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.? According to Josephine Cobb:

“Feeling some anxiety about the failure of the Washington Gallery to show a profit, Brady sent one of his best New York operators to look into the mode of operation of James F. Gibson. The new man was Anthony Berger, an excellent photographer. Gibson resented the interference and complained bitterly that there was no demand for war views and card photographs; he found it difficult to obtain apprentice photographers to replace those who had gone elsewhere …”

In addition to grappling with what James F. Gibson claimed to be slackening demand for Brady’s War Views stereocards and employee recruitment and retention issues, the Diary of Horatio Nelson Taft, 1861-1865 offers some additional insights. Taft worked in the Patent Office in Washington City during much of the Civil War and recorded in his diary, now at the Library of Congress, the following entry excerpt for Tuesday, April 1, 1862:

“A fine pleasant day. Went down to the Ave in the morning, got Draft of $20, sent to Mrs Barnes Phila. Called at McClees Photograph Rooms. He told me that he had mounted 2300 pictures the day before. The call for Photographs by Army officers has been unprecedented the past six months.” (See The Diary of Horatio Nelson Taft, 1861-1865. Volume 1, January 1, 1861-April 11, 1862, (http://www.loc.gov/resource/mtaft.mtaft1/).

McClees was one of Brady’s main competitors in Washington, D.C. Taft’s discussion with Mr. McClees illustrates the huge volume of work performed by the top Washington photographic studios at least early in the war as a result of the influx of soldiers in, and other visitors to, the city. Brady, likewise, experienced significant customer traffic in his New York locations:

“Lights burned late in Brady’s gallery as his operators prepared thousands of the cardboard pictures. Sometimes, when a new ‘issue’ was announced, crowds would flock to Fulton Street, push their way up the stairs to the gallery and clean out Brady’s stock within a matter of hours. At one time, the Anthony’s [who printed Brady’s war photographs] later recalled that they were printing as many as 3,600 cards a day.” (Horan, Mathew Brady: A Historian with a Camera, at p. 22).

Mr. Taft also visited Brady’s Washington City studio, writing on March 6, 1863 that: “… I went down on to the Ave, droped [sic] into Bradys Photograph Gallery which is one of the Institutions of Washington. Genl Sumner of the Army was there and I was introduced to him by my friend the Artist Mulvaney and had some conversation with him.” (See Volume 2 of Taft’s Diary). On March 10, 1864, Taft wrote of taking his daughter Julia to “Bradys ” last week where she sat for her picture which we shall soon have. The Artist who is to touch them up with his pencil came to see her last evening.” (http://www.loc.gov/resource/mtaft.mtaft2/seq-40#seq-67). by Craig Heberton IV, published March 8, 2014 (To be continued).

(Part II, supplemental update)

American Art Annual 1898 (1899), edited by Florence N. Levy, contains a compiled list of over 3,000 American artists. Within a directory of “Painters” in that book, at p. 426, appears a listing for “BERGER, ANTHONY.” It reveals that Anthony Berger had been a “pupil [at the] Staedelehe Institute” in Frankfurt, Germany (several other sources confirm the same). I assume that the “Staedelehe Institute” reference is an old description or slightly perverted spelling of the Staedelsches Kunstinstitut or the Städelschule/ Staedelschule, an international institute of fine arts in Frankfurt which was created from a foundation established in 1815 by Frankfurt banker and spice merchant Johann Friedrich Städel. Mr. Städel collected hundreds of paintings, etchings, and drawings during his lifetime and desired to create both a museum for his collection and a school (schule) for artists. After Städel’s death, legal proceedings tied up the settlement of his estate for many years until 1829. Today the school is considered one of the finest art academies in Europe and the associated museum gallery is rated as one of Europe’s best. Unfortunately the archival records relating to the time period when Anthony Berger would have been a pupil there were destroyed during World War II. This school must have been where Anthony Berger’ artistic talents first were cultivated.

The year before he changed his first name to “Anthony” to coincide with his naturalization in 1861, Anton Berger exhibited one of his paintings which he called “The Rendezvous” at the National Academy of Design (now known as the National Academy). Mary Bartlett Cowdrey (comp.), National Academy of Design Exhibition Record, 1826-1860, Volume I (1943), at p. 32. The exhibition probably was shown in a building then occupied by the Academy at Broadway and Leonard Street or 663 Broadway, New York City. Thus far, efforts to track down that painting have proven unsuccessful.

by Craig Heberton, published April 30, 2014 (To be continued).

->

(Part III – Hanover Junction, PA)

->

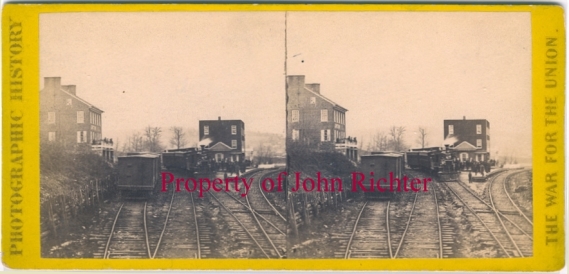

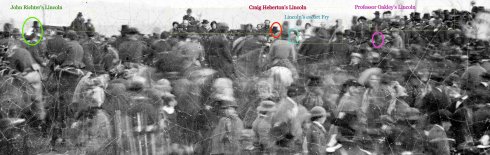

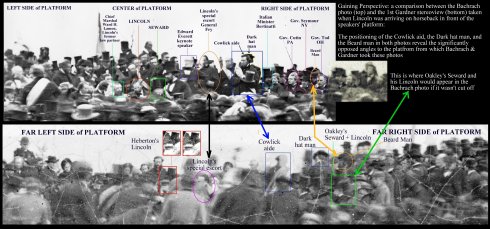

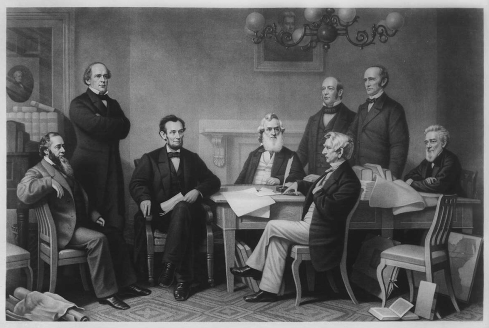

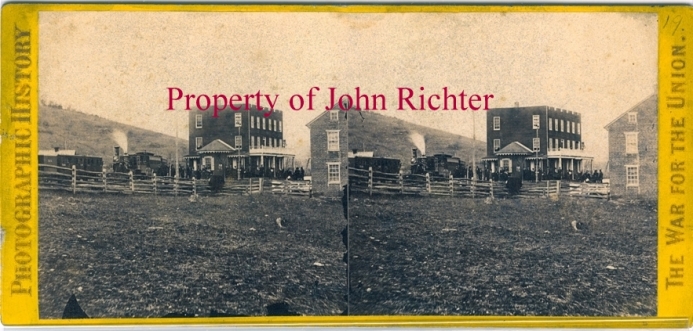

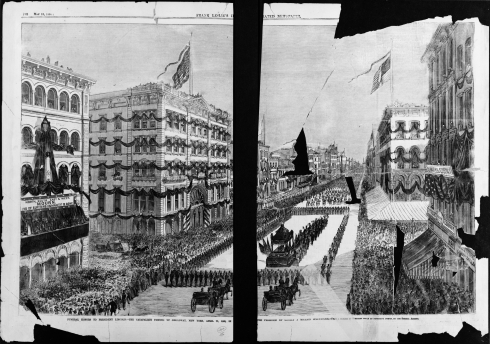

Mathew B. Brady, Anthony Berger, David B. Woodbury, and at least one additional Brady assistant joined together in Gettysburg days after the cessation of hostilities in July of 1863. For perhaps a full week they focused their attention upon photographing the suddenly famous terrain. The public’s appetite to see what the field of battle looked like was whetted. Gettysburg’s fame had been earned as soon as the readers of the northern press digested lengthy and spell-binding accounts of the three days of fighting which culminated in a stunning defeat for Lee’s Army of Virginia. During their several days in Gettysburg, Brady’s men managed to expose 36 known photographic plates, mainly in stereoscopic format — an average of only about 6 a day. Likely a few months later in a tiny hamlet about 25 miles east of Gettysburg, some photographers took 6 outdoor scenes late in the afternoon of a single day, nearly all of which were shot in stereo. Although the location photographed was described by some unknown scribe as a “point of note during the invasion of Lee in 1863″ (see below), those six hastily composed photos depict neither a battlefield, the home or birthplace of a famous person, the site of any important or infamous event, nor a place known to most Americans either then or now. Any evidence of damage wrought by Confederate cavalrymen was long gone by the time those photos were taken. Questions about why so many of those images were exposed, by whom they were taken, and what they depict have lingered and been debated for decades. Nearly a century after their creation, even the state in which the photographs were recorded remained a complete mystery to most of the National Archives curators.

->

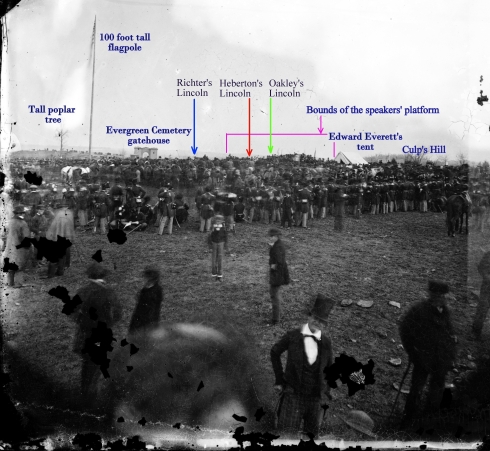

William A. Frassanito writes in

Early Photography at Gettysburg (1995), at p. 416, that Josephine Cobb, the former Director of the Still Picture Branch of the National Archives, shared with him several of her notes about her review of the contents of a private collection of papers written by David B. Woodbury covering some of the time period Woodbury worked for Mathew Brady. According to Mr. Frassanito, Cobb’s “notes indicate that Woodbury’s papers for July 1863 are missing, and made no specific reference to Woodbury having attended the November 1863 dedication ceremonies.” Two years later, Mr. Frassanito reiterated that “neither Brady, nor any cameramen affiliated with Brady’s firm, are known to have covered the November 1863 dedication of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg.”[1] Because the Woodbury papers remain in private hands and unavailable for research, photo-historians reached a dead end in their quest to determine if Brady or any of his assistants witnessed and attempted to photograph Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

->

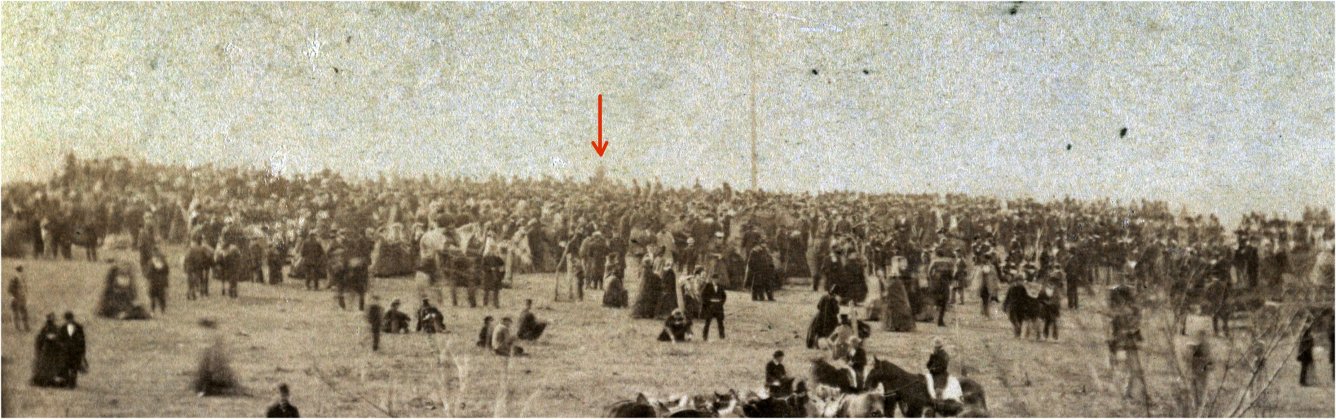

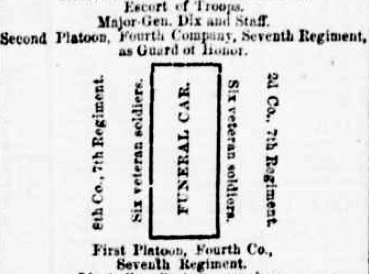

But as revealed in “The Brady Bunch: The Case of the Missing Gettysburg Photos,” it is now known that within the David B. Woodbury private collection there is a letter from Woodbury which he penned from Washington, D.C. to his sister Eliza, dated November 23, 1863, which states in part: “I went to Gettysburg on the 19th with Mr. Burger [sic] the superintendent of the Gallery here. We made some pictures of the crowd and Procession … We found no trouble in getting both food and lodging.” Although the owner of that letter has confirmed to me that it does not disclose much more detail about what Messrs. Woodbury and Berger did in Gettysburg, this correspondence establishes that Brady sent the same two ace photographers who were with him in Gettysburg in July of 1863 back to that town about 4 1/2 months later to cover the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery and Lincoln’s presence there. No one, as of yet, has definitively identified any November 19, 1863 photos taken by Berger and Woodbury in Gettysburg, but those men may well have taken photographs en route to or from the Gettysburg cemetery dedication event.

->

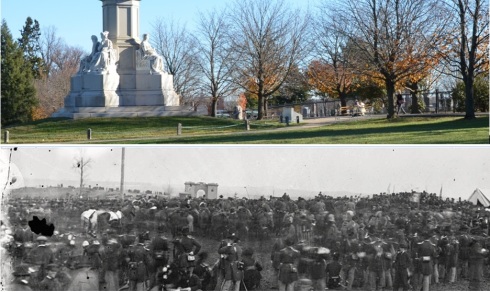

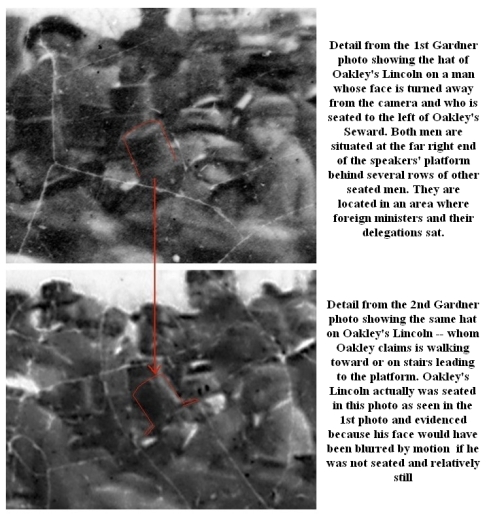

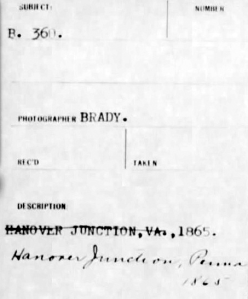

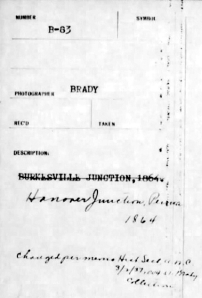

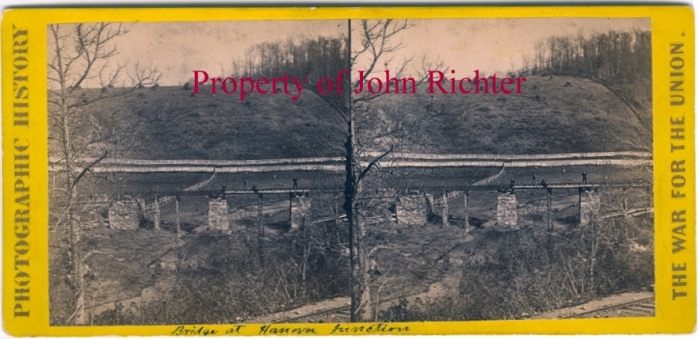

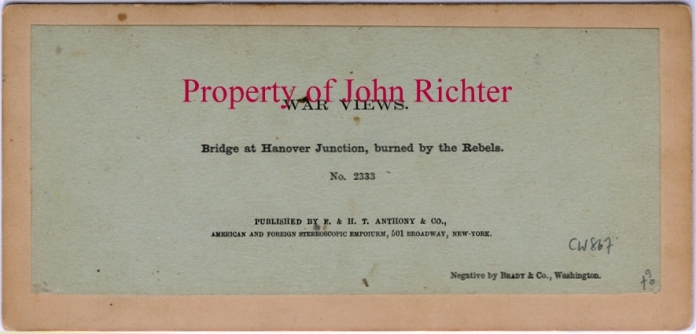

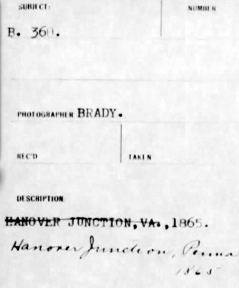

Mr. Frassanito has described a series of at least six negatives taken at Hanover Junction, PA, located about 25 miles east of Gettysburg, which are credited in “the earliest surviving identifications” to “Brady & Co.” See examples of two of the jackets from the National Archives, below:

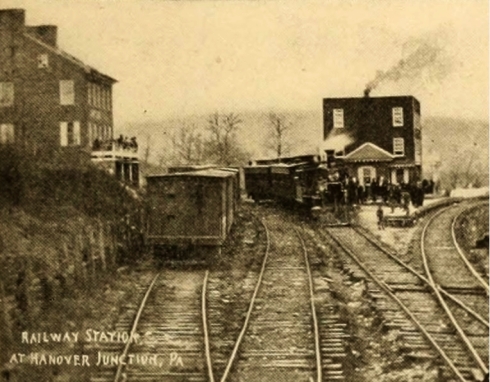

The oldest surviving captions from this particular series misidentified them as views of Hanover Junction, Virginia from 1864 or 1865. It is now well-established that they depict Hanover Junction, PA rather than VA. This conclusion is readily apparent when the images are compared to the surviving railroad depot in Hanover Junction, PA and what is left there of the extant tracks and rail beds. See, e.g., an article and corresponding “then and now photos” published in the

Gettysburg Daily on December 3, 2008 at

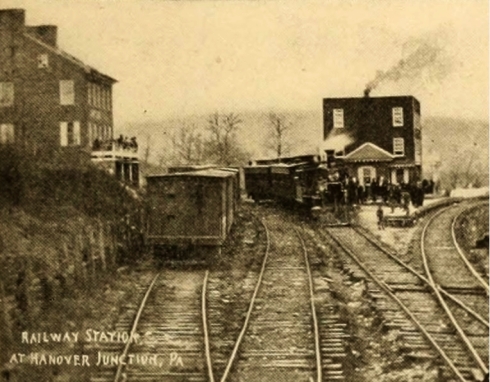

http://www.gettysburgdaily.com/?p=1121. Also, railcars of the North Central Railway (marked “NCRW”), which passed through Hanover Junction, PA, can be seen sitting at rest on an adjacent railroad siding in some of the photos. See “Crowds Await Transfer to Gettysburg for Dedication of the National Cemetery in Nov. 1863” (March 7, 2012), at

http://www.yorkblog.com/cannonball/2012/03/07/crowds-await-transfer-to-gettysburg-for-dedication-of-the-national-cemetery-in-nov-1863/, by Scott L. Mingus, Sr.

->

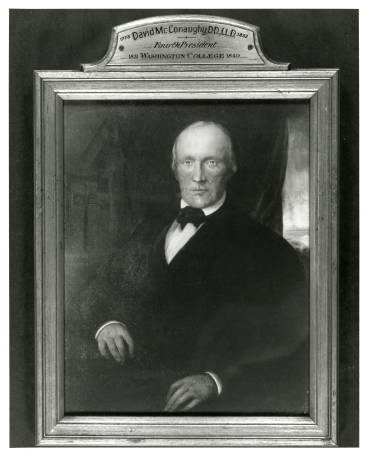

According to an article in the May 2, 1953 Gettysburg Compiler, entitled “More Brady Pix Discovered,” two grand nieces of Mathew Brady “discovered in Brady’s old studio” a book published two years before Brady’s death containing three of the Hanover Junction photos. That piece — The Memorial War Book (1894) by George F. Williams — contains numerous photos attributed to the teams of Brady and Alexander Gardner and was the first published photo-engraved book of Civil War photography. The three Hanover Junction photos appear at p. 395 of that book, and are correctly represented under the master caption “Scenes of Hanover Junction, Pa.” Even more remarkably, they are placed in a grouping with images and text relating to the Battle of Gettysburg campaign. On June 27, 1863, Confederate forces raided Hanover Junction, cut the telegraph wires, and burned the covered railroad bridge which spanned the adjacent Codorus Creek. By some unknown means that book’s author correctly determined where those photos were taken and used them to illustrate events in 1863 (see example, below). As revealed above, the National Archives apparently notated on the plate jacket belonging to at least one of the photos in March of 1937 that the Virginia location was incorrect. But not until Josephine Cobb figured out the mistaken location in about 1950 did the National Archives finally change its descriptions for all of the views in its collection. See “Claim Photo in Times Was Abe Lincoln,” The Gettysburg Times, October 11, 1952.

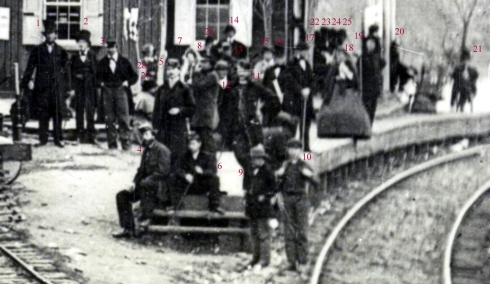

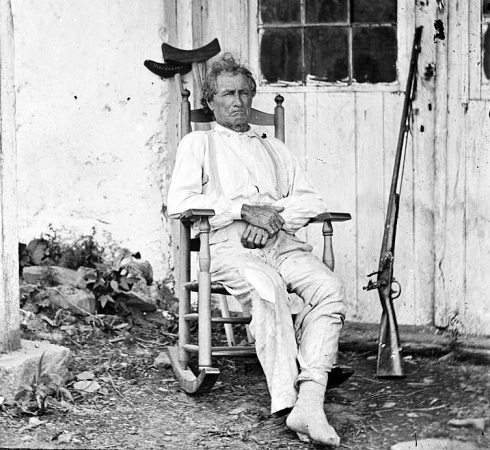

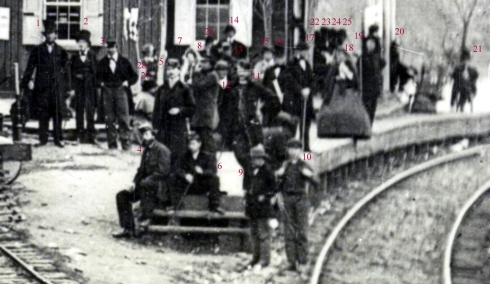

Mr. Frassanito writes that “all of the available evidence, including the barren foliage, does tend to support [a] November 1863 dating” of the Hanover Junction views. The Gettysburg Then & Now Companion, at p. 58. The manner of dress worn by the people posing in the images indicates that they were journeying to or from a formal event and supports a late fall dating. Several soldiers, young and old, can be seen with canes (in one case, a military man uses two of them like crutches) suggesting that they had sustained leg wounds and no longer were in active duty (see detail below from a gelatin silver print on a card mount, courtesy of the Library of Congress).

Might they have been wounded veterans of the Battle of Gettysburg traveling to or returning from the site of that bloody engagement, explaining why they (excluding the two men preening in the left foreground) and four bonnet-wearing women were the centerpiece of this particular view? These apparently wounded men may have been convalescing nearby at the York General Hospital, located to the north near the North Central Railway station in York, PA, and found themselves stranded in Hanover Junction with passengers from Washington who had reached that place by passing through Baltimore at the southern end of the North Central Line. In short, the Hanover Junction photos may reveal passengers who had come on two different trains from opposite directions and been deposited at the same station awaiting transport to Gettysburg. See also detail, below, from a different Hanover Junction view in which several soldiers (marked #s 4, 5, 6, 8 & 11) pose in a forward position:

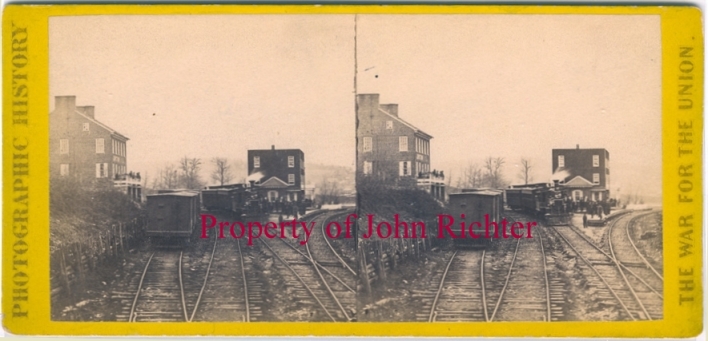

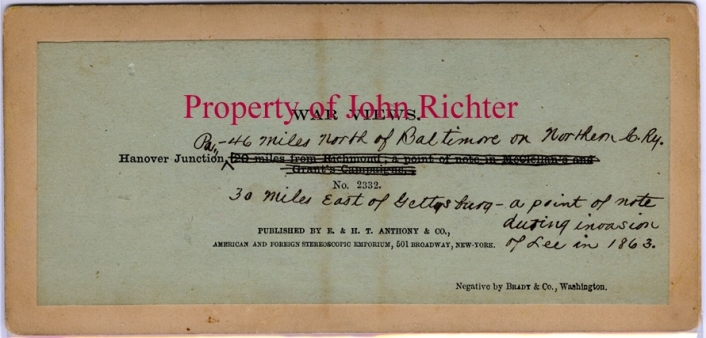

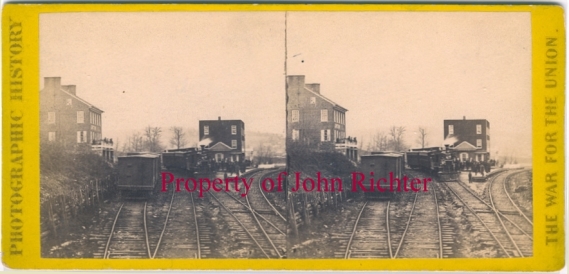

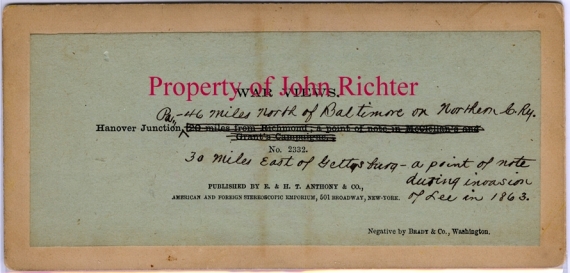

E. & H.T. Anthony & Co. contemporaneously published at least four of the stereo views taken at Hanover Junction in its The War for the Union series of stereocards, noting on each card’s verso that the negatives were by “Brady & Co., Washington” (See “The War for the Union, War Views” #s 2330, 2331, 2332, and 2333). Anthony & Co. also printed and sold other Civil War photographers’ works. If one of the Anthony & Co. stereo cards designated Brady as the supplier of the negative, it can be said with a very high degree of probability that the photo was taken by a Brady photographer. For example, the front and back images of an original Anthony “War Views” card #2332, taken at Hanover Junction, appear below, courtesy of John Richter:

The Library of Congress attributes the Hanover Junction views to “Mathew B. Brady or assistant.” In summary, this information, Mr. Frassanito’s analysis, and the more recently gleaned evidence that Brady sent Berger and Woodbury to Gettysburg in November 1863, constitute substantial support for crediting the Hanover Junction series of photographs to Messrs. Berger and Woodbury.

->

Why might two Brady men have exposed photographic plates at, of all places, Hanover Junction? In short, all train passengers traveling from Washington, D.C. to Gettysburg, and vice-versa, had to go through Hanover Junction, PA. It was there that two railroads met — the North Central Line and the Hanover Branch Line, the latter of which ran westward to and ultimately terminated in Gettysburg on the Gettysburg Railroad. It is reasonable to presume that both Berger and Woodbury were transported to Gettysburg from D.C. by railcar in November of 1863, twice placing them in Hanover Junction. Because Woodbury’s letter to his sister specifies that he and Berger had no trouble finding lodging in Gettysburg, it is very likely that they arrived in Gettysburg no later than on November 17, 1863 — before the most substantial crowds descended upon the town in droves. This is a reasonable supposition in light of the several accounts detailing significant train delays and the huge volume of Gettysburg-bound passenger traffic on November 18 and 19, as well as the problems those late arriving out-of-town guests had in securing lodging. A reporter for the New-York World didn’t mince any words: “The railroad facilities were very bad, especially between Hanover Junction and Gettysburg. I am informed that the best was done that was possible, but that may or may not mean anything. The passengers were compelled to crowd into dirty freight and cattle cars, and in that manner to ride a distance of some thirty miles, to their individual and universal discomfort.” Another correspondent wrote that in Gettysburg on the night of the 18th, “hundreds slept upon the floors of the [churches,] inns and private residences, and hundreds more took a rigid repose in the [train] cars or carriages...” With only four ordinary-sized hotels and all Gettysburg-area residences overflowing, “there were many people walking the streets, unable to get any accommodations for the night.” Tim Smith, “Twenty-Five Hours at Gettysburg,” Blue & Gray Magazine, at p. 14 (Fall 2008), quoting “Dedication of National Cemetery,” Gettysburg Star and Banner, November 26, 1863 and Daniel A. Skelly, “A Boy’s Experiences During the Battle of Gettysburg” (1932) at p. 26.

->

Ward Hill Lamon, Lincoln’s former law partner from Illinois, the President’s de facto body guard, and the U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia, was selected to serve as the Marshal-in-Chief for the November 19 dedication ceremonies in Gettysburg. To this end, on November 17, he made the journey from Washington to Gettysburg along with a number of judges, politicians, journalists, dignitaries, and friends, several of whom were to serve as Lamon’s aides at the National Cemetery dedication ceremonies on the 19th. The Ward Hill Lamon Papers at the Huntington Library reveal that twelve men who agreed to serve as aides signed a petition “signifying their intention of accompanying Marshal Lamon to Gettysburg tomorrow — leaving this city at the hour unnamed (undated).” Among the men accompanying Lamon were Benjamin B. French, Judge Joseph Casey, John W. Forney, Solomon N. Pettis, and John Van Risiwick. A journalist who accompanied Lamon on the 17th (perhaps John W. Forney) wrote the following account, published on November 18 in the Philadelphia Press and the Washington Daily Morning Chronicle:

->

“[Mr.] Lamon and a number of his aids … left Washington this morning, at a quarter past eleven o’clock, for Gettysburg, in special cars, kindly provided by W.P. Smith, of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. They arrived in Baltimore at one o’clock, and repaired to the Eutaw House, where a sumptuous dinner was partaken of, by the courtesy of Mr. Smith. At three P.M. the party left for Hanover Junction, in a special car furnished by the officers of the North Central Railroad. Here we are detained, no car being ready to convey the party to Gettysburg.”

->

Given Mathew Brady’s high profile, it is possible that Lamon invited the head of Brady’s D.C. photography studio and his colleague, Mr. Woodbury, to ride with him to Gettysburg — for free, no less. If so, Messrs. Berger and Woodbury would have found themselves stuck with Lamon in Hanover Junction in the mid-to-late afternoon of the 17th with a lot of time to kill waiting for a connecting train to Gettysburg, explaining why they might have unloaded their photographic equipment and exposed several plates in Hanover Junction. See, for example, detail from one of the photos (below) showing the photographers’ portable darkroom deployed along a fence line adjoining one of the tracks.

The author of “Crowds Await Transfer to Gettysburg for Dedication of the National Cemetery in Nov. 1863,” noted above, estimates that a Hanover Junction photo reproduced below was taken at approximately 4:00 p.m. on November 18, 1863. If the time of day is correct, it would fit into the timetable for when the Lamon contingent was stranded in Hanover Junction waiting for a connecting train to appear on the 17th. As noted in the October 11, 1952 edition of The Gettysburg Times, “shadows indicate the time of day would be shortly before [a November] sunset.” Thomas Norrell took Hanover Junction photographs “in mid-November of 1953 at 3:30 p.m. which [he claimed] have exactly the same shadows.” The Gettysburg Times, January 1, 1954.

->

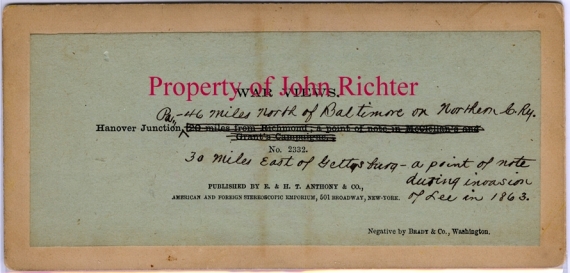

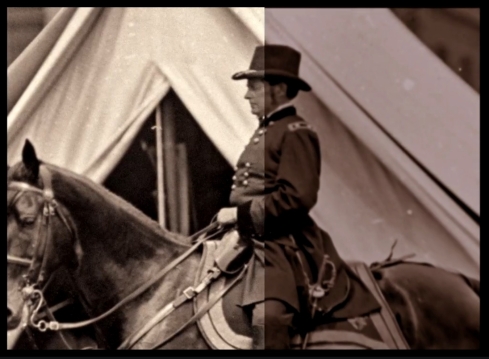

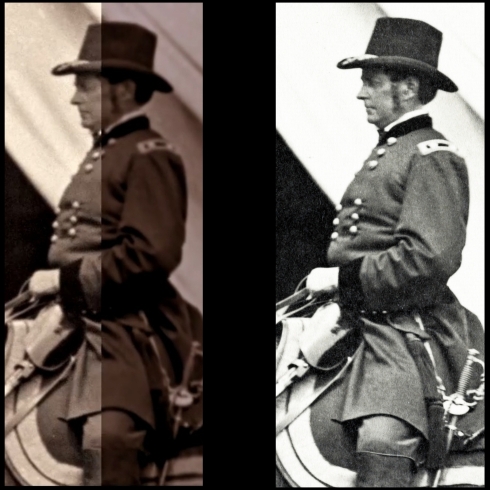

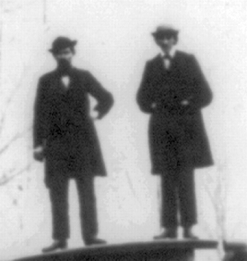

In one of the Hanover Junction photos, two men stand prominently atop a parked train car hitched directly behind a locomotive (see a print on a card mount in the Library of Congress collection, below, which was cropped down from the more expansive National Archives B-83 negative). They are the most discernible people in the print and possibly the chief targets of the cameramen. Perhaps the men standing atop the train are Ward H. Lamon and his brother Robert, who served as an aide for his older brother at the Gettysburg dedication ceremonies? Robert, who also served as an Assistant U.S. Marshal under Ward H. Lamon in Washington, was then 28 years old; his older brother was 35.

See detail, below left, of the two men as well as detail, below right, featuring them prominently within a different Hanover Junction view taken looking towards the eastern-facing side of the depot.

Compare these men with a studio photograph of Ward Hill Lamon (courtesy of the Library of Congress) credited to Mathew Brady and a carte de visite of Robert Lamon from about 1864:

Compare these men with a studio photograph of Ward Hill Lamon (courtesy of the Library of Congress) credited to Mathew Brady and a carte de visite of Robert Lamon from about 1864:

Is it possible that they are the same men? Might this explain why Berger and Woodbury possibly exposed several of their precious glass plate negative slides even before they arrived in Gettysburg?

->

The goateed man with the bowler hat also appears in a stereo view scene depicting a railroad bridge over Codorus Creek (see below, in close-up detail, courtesy of the Library of Congress). The approximate center point of that North Central Line bridge, where the man sat, is no more than about 250 feet from the eastern side of the Hanover Junction railroad station. The camera was set up about 400 to 500 feet from the station house next to the Hanover Branch Line tracks and faced the Codorus Creek bridge looking in an east by northeasterly direction. The sunlight cast on the man illustrates that the plate was exposed late in the afternoon when the sun was low in the southwestern sky. I estimate the distance from the camera to the man on the bridge at about 325 to 375 feet. Was Ward H. Lamon the sort of man who might have walked out onto a train bridge, sat on the end of a railroad tie in the middle of the bridge, and there dangled his feet in order to pose for a stereo photograph? Would Anthony Berger or David Woodbury have asked W.H. and Robert Lamon to do such a thing, let alone climb atop a railroad car, or might Ward H. Lamon — Lincoln’s self-proclaimed bodyguard and the U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia — have directed the camera operators to photograph him and his brother in several poses demonstrating their virility?

Three other males joined the goateed man on the bridge. Only one of them also sat on the end of a railroad tie, but that man chose a somewhat safer spot where his feet firmly rested upon a large, squared log directly above one of the bridge’s massive stone foundations in the middle of the creek. He is the same fellow seen standing with the goateed man in the two other Hanover Junction views previously discussed and who may be Robert Lamon (see a comparison, below).

Is the goateed man Ward Hill Lamon, who was captured in this and two other pictures by the photographers as a form of payback for providing free transportation to Gettysburg, or is he simply a historically irrelevant figure with a goatee who prominently inserted himself (along with a younger man) into three generic Berger & Woodbury views which were taken only with the object of photographing buildings and structures rather than specific people or groups of significant people in various scenes?

Because the only other people photographed on the bridge are a boy shielding his eyes from the sun with his right hand (see above) — standing between the men who may be the brothers Lamon — and one of the interloping men preening before the camera in the view showing military men and several women on the station house platform (see a side-by-side comparison, below), it appears that the goateed man and his side-kick again were the primary human subject matter posed within in a Hanover Junction photographic view taken by the Berger-Woodbury team.

In his book The Gettysburg Soldiers’ Cemetery (1993), Professor Frank L. Klement describes Ward H. Lamon as “stout, most handsome, and possessed of a swashbuckling air.” Despite an apparent penchant for striking swashbuckling poses and the resemblance of his younger side-kick to Robert Lamon, is the goateed fellow burly enough or even tall enough to be Ward H. Lamon? Would Lamon have been inclined to cut his hair that short before he served as the Chief Marshal at the Gettysburg Soldier’s Cemetery dedication event? Was Lamon clean-shaven or sporting a goatee in November 1863? Part of the difficulty in making any conclusive identification of the possible Lamon figure is that there are not, to my knowledge, any dated photos of him from 1863, let alone in the fall of 1863, to use as a base of comparison. A hatless man with a goatee seated next to Lincoln on the Gettysburg speakers’ platform visible in the so-called David Bachrach photo taken on November 19, 1863 might by W.H. Lamon, but it is more likely that he is one of Lincoln’s personal assistants, John Nicolay, especially given where he is seated. Whether or not Ward H. Lamon is in the Hanover Junction views, however, is a mere sidelight to a bigger question. Again, quoting Professor Klement, he writes: “on the next day, November 18, most of Lamon’s friends and aides toured various parts of the vast battlefield [in Gettysburg].” If Messrs. Berger & Woodbury accompanied Lamon to Gettysburg on the 17th, they probably revisited portions of the Gettysburg battlefield on the 18th, perhaps even famous locations they had missed in July such as Meade’s headquarters at the Lydia Leister house, Devil’s Den, and John Burns’ home. It is exciting to speculate that these men took more Gettysburg battlefield views which have yet to be discovered.

->

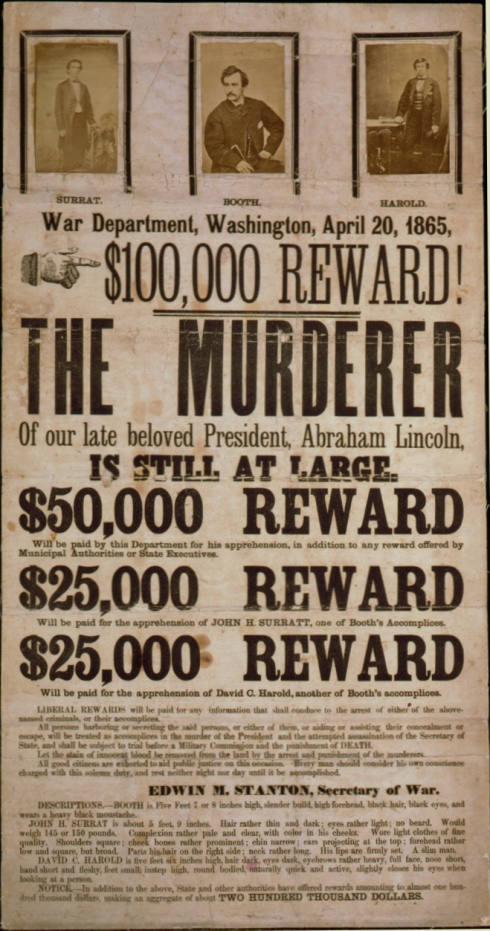

Whereas searching for the tandem of Ward Hill and Robert Lamon was not the impetus behind this review of the Hanover Junction photos, other researchers have engaged in the search for Gettysburg dedication ceremony luminaries in the Hanover Junction images for more than a half century. For a number of years particularly Thomas Norrell, a collector of old locomotive photos, and Russell Bowman, President of the Lincoln Society of Hanover Junction, argued that President Lincoln is visible in at least one of the Hanover Junction views. Their position first was made public prior to Josephine Cobb’s November 1952 disclosure of Lincoln’s visage in a Gettysburg Soldiers’ National Cemetery dedication photograph. Until then, it was “pretty well agreed [by and among Lincoln scholars] that the Great Emancipator was never photographed either at or on his way to Gettysburg, Pa.” The Gettysburg Times, October 11, 1952. The advocates of Lincoln’s presence in a Hanover Junction photo — the one depicting two men standing atop a parked train car, seen above — assert that a whiskered figure in a stovepipe hat standing largely unattended on the platform near the locomotive is President Lincoln (see detail below, Library of Congress).

When originally disclosed to the media, this photo created a “buzz” as it was held out as the possible first photographic discovery of Lincoln’s image in connection with his visit to Gettysburg. After the Western Maryland Railway Company released the photo in early October 1952 “calling attention to the ‘tall man’ in the stove pipe hat … experts and amateurs alike jumped into the controversy. Art editors sent the photo throughout the country. Life Magazine pondered the problem and set the prints before its readers.” The Gettysburg Times, January 1, 1954. One of the arguments asserted in support of the “Lincoln was photographed at Hanover Junction” theory is “the fact that the picture was made at all by the famed Brady … indicate[s] an event of some importance in Hanover Junction.” Despite initial skepticism over — and even out-right rejection of — the claim that Lincoln was photographed at Hanover Junction expressed by notables such as Ms. Cobb, numerous Lincoln scholars, and photo-historians, The Gettysburg Times on June 17, 1953 described the photo in question as “the famed Hanover Junction picture, which many claim depicts Lincoln enroute to Gettysburg.”

->

Without now parsing through the several contextual arguments running counter to the “its Lincoln at Hanover Junction” theory, I’ll simply note that today’s high resolution digital scans reveal that the man does not look at all like Lincoln. Moreover, if Ward H. Lamon and his brother Robert are visible in several of the Hanover Junction views, then the whiskered man cannot be Lincoln because Lamon traveled to Gettysburg the day before Abraham Lincoln left Washington. Which leads us back to some remaining questions — are these views merely generic scenes of the Hanover Junction railway station and surroundings taken in November 1863 which just happened to be populated with a number of stranded passengers or did the photographers compose these images purposefully and place a specific person or persons of notoriety in one or more of their stereoscopic scenes? Also, assuming that the images, in fact, were exposed around the time of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, did Anthony Berger and David Woodbury take them on the way to or back from Gettysburg? If Berger and Woodbury took these views in connection with their now documented trip to Gettysburg, what happened to the views they took in Gettysburg of “the crowd and Procession?” How is it that four of their Hanover Junction views were published by E. H. & T. Anthony & Co. but none of their Gettysburg dedication event views are known to collectors and historians? Ah, the secrets that have yet to be revealed …

->

By Craig Heberton, May 4, 2014 (to be continued)

->

[1] “The Daguerrean Art – Its Origin and Present State,” Photographic Art-Journal, March 1851, Vol. I No. 3, at p. 138.

[2] Meredith, Roy, Mr. Lincoln’s Camera Man, Mathew B. Brady (1974), at p. 79.

[3] Possibly in Humphrey’s Journal of the Daguerreotype and Photographic Arts, Vol. V (1853).