Girl, Interrupted

The photographer Annie Leibovitz is best known for her magazine shoots of actors, rock stars, models, politicians, and other luminaries appearing on the covers of old-line vanguard publications such as Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair and Vogue. Her many photographic successes long ago vaulted her into the same exclusive club occupied by many of her subjects — celebrityhood. In more recent years, however, Ms. Leibovitz’s life experiences have sent her veering off in dramatically different directions.

The Big Bounce (Back)

First came the publication of her deeply personal and introspective book titled A Photographer’s Life 1990-2005 (2006), which Sarah Boxer describes as:

“an unholy mix of celebrity portraits and snapshots from her private life, including pictures of herself and of [Susan] Sontag without clothes, of her family members dying and being born, of the hotels she stayed in and the real estate she owned, of herself pregnant at age fifty-one and, most famously, of Sontag laid out on her deathbed in a crinkly black dress. It was a tombstone of a book, heavy, gloomy, and unsettling.”[i]

Rebounding from that controversial publication, the deaths of family members and her partner Sontag, as well as her own personal bankruptcy — all of which severely tested her — Annie Leibovitz began a long-distance pilgrimage, of sorts. Along the way she traveled to many destinations on a photo assignment for no one other than herself. As she embarked on that journey an objective came into focus: to visually capture the power of, and stories behind, historic objects and locations which resonated with her — something more akin to her September 2001 images of Ground Zero, but executed in a far more up-close and personal fashion. At times she found herself moved to tears by objects which once belonged to dynamically creative and larger-than-life figures whom she reveres (including women such as Georgia O’Keefe, Marian Anderson, Virginia Woolf, Emily Dickinson, and Louisa May Alcott).

Night (and Day) at the Museum

Her favorite and most compelling photographs of objects from her travels hither and yon were placed in a book she aptly titled Pilgrimage (2011), the text to which she wrote with the help of Sharon DeLano. Scenes taken in places such as Gettysburg, which Leibovitz first visited as a child, also are represented.

The book has spawned several exhibitions of the photographs appearing on its pages, including at several institutions known less for their works of art than their displays of historically compelling objects and images, such as the Gettysburg National Military Park Museum and Visitor Center. Presently, the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, IL is hosting an “Annie Leibovitz: Pilgrimage” exhibition through August 31, 2014.

To Save A Life

Ms. Leibovitz’s description of her underlying motivation for the book reveals that Pilgrimage just as easily could have been christened “Salvation:”

“I NEEDED to save myself. I needed to remind myself of what I like to do, what I can do … There was a spiritual aspect to this journey at first. It didn’t stay at that level — because I began to feel better. But somehow, it saved me to go into other worlds.”[ii]

So how exactly did photographing anything other than living people “save” Annie Leibovitz and in what way did this open up new worlds to her? Leibovitz’s several interviews explain how she came to the realization that an inert object with a storyline or context connecting it to an inspirational historical figure can metaphorically “speak” to us, the living, on a very personal level. She also concluded that it was possible to photograph those objects in a way that would allow others to form their own powerful connections to them and the famous people to whom they once belonged.

Deep Impact

Ms. Leibovitz’s insights, interestingly, emerged at a time that physical objects from our nation’s past are losing much of their appeal, especially to the youngest generations of digitally-obsessed Americans. To the historically challenged, old objects merely represent “stuff” that is irrelevant to their lives and symbolically linked to a past they often care little to know. Perhaps Ms. Leibovitz’s photographs and accompanying narrative in Pilgrimage will arouse their curiosity to explore exactly why for several years a famed photographer NEEDED to focus her camera on historical objects rather than the hottest celebrity de jure. In Leibovitz’s own words:

“I had to learn to photograph objects. We don’t know [a famous person like] Thoreau, do we? We have only his work, and his things. When I first saw the cane bed he slept on, I was so overwhelmed, I didn’t know how to deal with it … I have a bit of a feeling that I’ve had it with people. But you don’t ever get away from people, really. And these are pictures of people to me. It’s all we have left to represent them. I’m dealing with things that are going away, disappearing, crumbling. How do we hold on to stuff?”

Being There

One object which Ms. Leibovitz was drawn to photograph and feature on two pages of Pilgrimage merits special mention. Unlike nearly all of the other objects photographed for that book, Leibovitz was not attracted to it because of who once owned it or physically handled it.

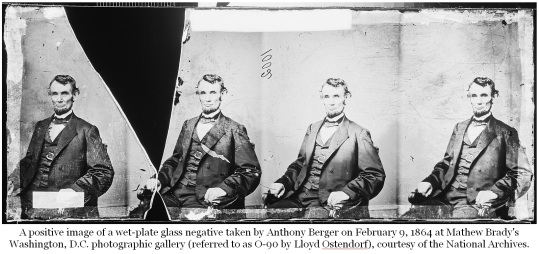

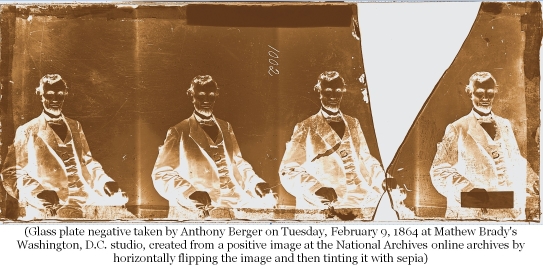

Her picture of this unique object is compelling on several levels, not the least of which is that it verges on qualifying as the product of a celebrity photo shoot. In a virtual sense, Ms. Leibovitz pointed her cutting-edge digital camera directly at the visage of Abraham Lincoln. Although space-time continuum barriers sadly prevented her from photographing Lincoln in the flesh, she still managed to gain access to the National Archives to photograph what may be an original wet-plate glass negative[iii] of four images of Lincoln created when he was seated in front of a multi-lens camera operated by Anthony Berger on February 9, 1864 in Mathew Brady’s Washington, D.C. photographic gallery. To view Leibovitz’s photograph of the Lincoln plate appearing in Pilgrimage, click here.[iv] Photographing this negative offered Annie Leibovitz the closest experience to “being there” with one of the most influential American figures of all time and a man who enjoys an exalted position in the pantheon of our most famous celebrities.

Ghost

At first blush, the four side-by-side negative images of Lincoln (backlit on a photo tray) are eerily ghost-like in appearance.

“It is this physical, and yet somehow ghostly, aspect of photography—its “spooky action at a distance” quality (to quote Einstein out of context)—that gives photography its particular aura. And this intensely interests Leibovitz.”[v]

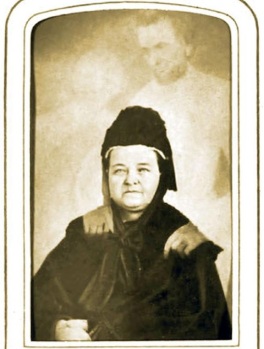

The glass plate images might even remind some of the handiwork of William Mumler, a Boston and New York-based photographer from the mid-19th century who created expensive studio portrait photos into which he inserted apparitional figures made to resemble deceased loved ones. Mumler claimed to be able to photograph spirits which magically appeared around his paying customers in the midst of a studio session. Joining a long list of other Mumler hoax victims, Mary Todd Lincoln visited his studio in the early 1870s to pose for a photo into which Mumler inserted the extremely wispy, bleached image of something looking sort of like her dearly departed husband standing over her with both of his hands lovingly resting upon her shoulders (as well as a less detailed white figure presumably representing her departed son Willie).[vi] Although very touching and reassuring for Mrs. Lincoln — who thought the photo was legitimate because she claimed to have introduced herself to Mr. Mumler under a pseudonym — it still was a fake.

Images of Mrs. Lincoln appeared in thousands of carte de visite prints sold both before and after her husband’s death.[vii] An example of a Brady photo of Mary Todd Lincoln copyrighted in 1862 appears below, left, and possibly another example from the same photo session, courtesy of the National Archives, to the right:

As she mourned for her husband, much of the nation mourned with Mrs. Lincoln by placing her calling card-sized image in their respective family photo albums. Mary Todd Lincoln would have been immediately recognizable to a then-successful big city photographer like William L. Mumler, even if he had never before met her, simply because he had handled and probably sold dozens upon dozens of pirated prints of her pictures taken in other photography studios, a practice then widespread among many professional photographers.

But there is nothing fake about the item photographed by Ms. Leibovitz; it is an unadulterated object. Adding to the dramatic visual effect of Anthony Berger’s delicate glass plate negative, two of its Lincoln images are beset with bisecting cracks from which pieces of glass have broken off from the slide. The consequences of rough handling over the years have extracted their toll. If Mr. Mumler was still alive, he might insist that the missing triangular-shaped wedges of glass are shaped like opposing dagger tips which hauntingly meet one another at the top and bottom of one of Lincoln’s hands, metaphorically nailing that hand to the arm of the chair. Were these cracks symbolically created by someone from the afterlife or are their locations and shapes just a mere coincidence? The correct answer must be: “Mum-ler’s the word!”

And That’s a Wrap

On yet another level, Leibovitz’s photo represents something far more meaningful than just a picture of a 150 year-old glass negative. I suppose that the object Annie Leibovitz photographed can be thought of as Lincoln’s version of the Shroud of Turin. Considering it from that perspective, it might even be viewed as a form of a holy relic.

The glass negative images were produced in consequence of Lincoln’s physical presence, during a few moments that particles of light bounced off of him, passed through the camera’s four optical lenses, and interacted with the chemicals on the surface of the exposed glass plate. This, in turn, imprinted his reversed image onto the plate in a negative format. In a sense, Lincoln MADE the images on the glass plate. This photo-chemical process (completed after “developing” and “fixing” chemicals were applied to the plate in a darkroom) rendered the three-dimensional Lincoln as a series of two-dimensional negative images on a thin piece of glass, harkening back to roughly how some people believe a crucified Jesus Christ imprinted an image of himself on his wispy death shroud now said to be in Turin, Italy.

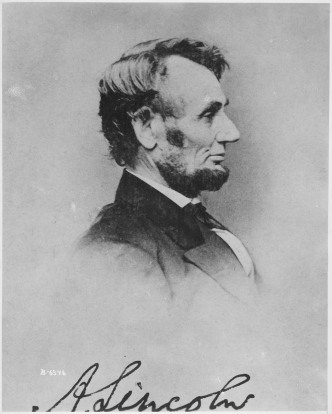

During her visit to the National Archives, Annie Leibovitz was able to see and photograph several other famous glass plate negative portraits of Abraham Lincoln taken by Anthony Berger in that same February 9, 1864 sitting, including the famous “Penny View” of Lincoln used as the basis for the image on the U.S. penny and the two Berger views used to create Lincoln’s image on the old and new $5 bills (two of those images appear below, courtesy of the National Archives; the one on the top, dubbed the “Famous Profile,” was used in conjunction with the very similar “Penny Profile” view by Victor D. Brenner for the Lincoln-head cent):

Leibovitz’s reaction to that experience was described by Sarah Boxer in the following way:

“When speaking of the photographic plates of Lincoln that were made by Anthony Berger at Mathew Brady’s studio (which were used as templates for the five-dollar bill and the penny), [Ms. Leibovitz] described them as “very spiritual” because ‘the photons that bounced off Lincoln had once passed through’ them. It is eerie to think that Lincoln’s very body physically affected the plates that captured his image.”[viii]

The glass plate negative slides of Abraham Lincoln housed at the National Archives also are “very spiritual” simply because they reveal moments of time, 150 years ago, burned onto a tiny layer of chemical film clinging to the slides’ surface. In Boxer’s words, Lincoln’s:

“body acted on the light in such a way that the light struck the photographic plate or negative and physically changed it to form an image. Every photograph [made in this way] is an indexical trace, a brand made by its subject.”

Using even more visceral terms, Boxer described all non-digital photographs produced on negative film as like “cattle branding: burning an impression into the cow’s hide, so that it will be forever linked to its owner.”

Jurrasic Park Meets the Nutty Professor in 3-D

Yet another metaphor borrowed from Christianity can be used to describe the inherent spirituality of Anthony Berger’s glass plate negative of Lincoln. In a sense, that object offers its viewers the chance to see a version of Lincoln resurrected from the dead and visually brought back to life into our modern spatial world of three dimensions. To achieve this result, we need only to reverse the process that converted Lincoln’s 3-D physical being into a series of 2-D negative images on a remarkably thin piece of glass. But how? What mad alchemist could possibly achieve this crazy sounding task?

Well, here’s how. The images of Lincoln were “branded” onto the glass plate by the photographer’s use of a single camera with at least one row of four side-by-side lenses. The spacing of those lenses more-or-less mimicked the distance between a human’s eyes. Consequently, the viewer can experience a 3-D effect when a set of those image pairs are viewed stereoscopically. Seen in this manner, Lincoln is optically “brought back to life” again in all three of his glorious dimensions.

Lloyd Ostendorf, co-author of Lincoln in Photographs: An Album of Every Known Pose, has concluded that Anthony Berger used a multi-lens camera in order to speed up the process of mass producing prints of Lincoln’s image. This means that at least the photographs of Lincoln shot with a multi-lens camera were taken — from Anthony Berger’s perspective — with the primary objective of selling a great number of prints (published by E.& H. T. Anthony & Co.) to the public. An unintended consequence of that business decision by Anthony Berger, however, was to permit future generations the ability to stereoscopically bring Abraham Lincoln “back to life” in 3-D from several moments in time on February 9, 1864.

Little Big Men

The pose struck by the Great Emancipator was choreographed and captured in a several second exposure as the result of the collaborative efforts of two men — Anthony Berger (the photographer) and Francis B. Carpenter (a painter who arranged for the session with Lincoln and helped orchestrate his poses). Mr. Carpenter convinced Mr. Lincoln to sit for this and twelve other photographic poses despite the President’s great impatience with the long, drawn-out process entailed in posing for what he called “sun pictures.” In fact, so impatient was Lincoln on the day of the February 9, 1864 photo shoot, that when his carriage was delayed, he chose to walk from the White House to Brady’s Pennsylvania Avenue studio and dragged Carpenter along with him. Carpenter quoted Lincoln as saying “I’m pretty much split up for our having had to wait like this.” It is amazing that Lincoln later was able to sit through seven poses at the studio on that day. The collodion process then used in making wet-plate negatives was lengthy and tedious both for photographers and the sitters.

Carpenter essentially was an “artist-in-residence” (in the words of Harold Holzer) at the White House for a six month period during the first half of 1864, enjoying what he described as “the freedom of [Lincoln’s] offices at almost all hours.”[ix] His interaction with Lincoln reveals both the special relationship he forged with the President and the great trust Lincoln placed in him. Carpenter obtained this level of intimate access after he pitched the following project to his President — to create a painting of Lincoln and his cabinet members in a scene entitled “The First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation Before the Cabinet.” Carpenter’s goal was to memorialize as historically accurately as possible what he considered to be one of the greatest moments in the history of mankind.

As far as Francis Bicknell Carpenter must have been concerned, the photos of Lincoln which he arranged for Anthony Berger to shoot were to serve a singular purpose — to provide him with positive prints of Lincoln in poses desired for use as figure studies for The First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation Before the Cabinet. Any other poses struck by Lincoln and photographed by Berger, such as his “quiet family moment” view of Tad Lincoln standing next to his father while both stared at a photo album prop, would have been shot on Berger’s own initiative as they had absolutely no relevance to Carpenter’s painting of the The First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation Before the Cabinet. Granted, Carpenter later used that father-son photo as the very rough basis for two separate paintings (on a much, much smaller physical scale) titled “President Abraham Lincoln and Tad,”[x] which is part of the White House collection, and “The Lincoln Family,” at The New York Historical Society; but they and other similar paintings were afterthoughts and sidelights to his main objective. From the beginning, he envisioned that his Emancipation painting would be mass-produced in the form of engravings for all to see and enjoy, making his work well known, immensely popular, and a key part of America’s cherished historical record.

It is not known how it came to pass that Anthony Berger served as the photographer of Lincoln on each and every occasion that Carpenter arranged for a presidential photo session. Three Lincoln photo shoots occurred, on February 9, April 20, and April 26, 1864, the last of which was set in Lincoln’s study/cabinet room in the White House where the Emancipation Proclamation was first read. Some unknown cameraman (perhaps Berger?) also took five views of Lincoln at Brady’s Washington studio with a four-lens camera on January 8, 1864 and Thomas Le Mere photographed Lincoln in a standing pose on about April 17, 1863 when he worked for Brady in D.C.,[xi] demonstrating that other Brady men could answer the call to photograph the President. Carpenter also relied upon Anthony Berger to photograph at least some of the Lincoln cabinet members who were to appear in his painting, including Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton.[xii] Carpenter was not present for the session with Stanton, trusting Berger to follow his prior instructions on how to pose Stanton.[xiii] On one occasion, Carpenter even posed himself in front of Berger’s camera as a stand-in for Secretary of State William Seward to create the desired figure study pose for Seward in “The First Reading.“[xiv]

All of this points to the conclusion that Carpenter chose Berger to work exclusively on this several month long project and that he did so both because of their familiarity with one another and his admiration for Berger’s talents. If Francis Carpenter had preferred a man from one of the other highly-regarded studios in D.C. (such as Wenderoth & Taylor, at which Lincoln was photographed sometime in 1864, for example) or even a different Brady cameraman, he surely would have brought in someone other than Anthony Berger to help him with what he thought would become his greatest masterpiece and elevate him to the status of the exalted Gilbert Stuart or John Trumbull who famously painted George Washington.

Although Messrs. Holzer, Borritt, and Neely assign all of the credit to Francis Carpenter for how Lincoln was posed in the Berger photos, I don’t think that Berger’s formal training as a painter in Frankfurt, Germany should be discounted. Those three Lincoln scholars assert that:

“the great Lincoln photographs which became the lasting models for coins, stamps, and currency were composed under Carpenter’s eye: sittings before the same photographers did not produce equal results when Carpenter was absent.”[xv]

This conclusion ignores one point — that we only definitively know of a handful of the photos which were taken by Anthony Berger when he worked for Brady. In each such instance, that knowledge comes entirely from Carpenter’s published and unpublished writings. All of Berger’s known photographs involved Carpenter’s collaboration, perhaps with the exception of the supremely compelling photo that Berger took of Lincoln with his youngest son Tad. Thus, we don’t have a body of Berger’s work independent of Carpenter against which to compare. Granted, Carpenter “did have a keen eye for portraiture and documentary groupings,” but who is to say that Anthony Berger never took any other portrait photos without Carpenter’s involvement of equal or greater artistic merit? The Anthony Berger photographs, in the words of David Hackett Fisher, showed Lincoln “as a wise and experienced leader, with an aura of growing strength and confidence.”[xvi] Should that achievement be attributed solely to Carpenter, despite the fact that “there were doubts about Carpenter’s reputation even in his own day” and one modern art historian unfairly characterized him as a “very boring” artist? Or is it more likely that the combined talents of Carpenter and Berger produced photographs of Lincoln beyond either of their individual powers?

Branded (in a Good Way)

Besides creating memorable photographs “branded” onto photographic film, Annie Leibovitz has excelled at other forms of branding — in particular, linking the names of celebrities to her widely-recognized photographs of them. To think of a celebrity and then immediately conjure up in one’s mind their image from a Leibovitz photograph is a supreme achievement. Declares Sarah Boxer, “she is a genius at it.” By so succeeding, Leibovitz also has created her own brand.

The original concept of creating compelling photographic images of celebrities was most successfully executed in America first and foremost by the man who employed Anthony Berger for approximately a decade — Mathew Brady. It was Brady who created the widely recognized “Brady of Broadway,” “Brady’s National Photographic Portrait Gallery,” and “Photograph by Brady” brands. The celebrities photographed in Brady’s studios included Presidents, members of royalty, noted politicians, philosophers, religious figures, ambassadors, high-ranking military officers and heroes, actors, and even members of P.T. Barnum’s circus. These photographs of stars made Mathew Brady, in kind, a veritable rock star in his day. Few knew and hob-knobbed with as many of the rich and famous as Mathew Brady. Now, exactly 170 years after Brady opened his first studio, there are not many photographers as successful in the pursuit of ever-lasting images of celebrities as Ms. Leibovitz. At some point in her career of creating the equivalent of trademark images of stars, Annie Leibovitz has become her own brand just as Brady once did.

In the same way that Annie Leibovitz has proven herself a modern artistic genius by imprinting in our minds immediately recognizable photographs of celebrities — such as John Lennon naked and curled around Yoko Ono, Dolly Parton paired with Arnold Schwarzenegger, Dan Akyroyd and John Belushi as the “Blues Brothers,” Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.,” Demi Moore naked and pregnant, etc. — with “the props, the settings, the clothes, and even the gestures and expressions that will cling to each person’s image … linking one to the another,”[xvii] so too were Anthony Berger and Francis B. Carpenter geniuses. Their collaboration, which resulted in thirteen known poses of Lincoln, produced several which are immediately recognizable and considered iconic a full century and a half later. Yet, because those photos were linked for the better part of the last 150 years only to Mathew Brady, any fame and notoriety due to Messrs. Berger & Carpenter has gone largely missing. Their story would have a modern-day parallel if, for example, it were to be demonstrated conclusively that the crème de la crème of Annie Leibovitz’s most iconic photographs over the last several decades were not taken by her, but by an obscure younger protégé in her employ essentially unknown to the art world [Note: this is nothing more than a hypothetical used for illustrative purposes].

Excuse My Dust

In her “Annie Leibovitz’s Ghosts” piece, Sarah Boxer quotes part of a passage (and the title) from Walt Whitman’s 1871 elegy to Abraham Lincoln, among his “Leaves of Grass” compiled works, which Whitman began after Lincoln was assassinated in April of 1865:

This dust was once the man,

Gentle, plain, just and resolute, under whose cautious hand,

Against the foulest crime in history known in any land or age,

Was saved the Union of these States

Boxer then rhetorically asks “when you hear the name Annie Leibovitz, what images spring to mind?” Answering her own question, she listed several easily recollected celebrity photos by Leibovitz. But Boxer also posits that as a result of Leibovitz’s photo of Anthony Berger’s multi-lens glass plate negative of Lincoln appearing at pp. 89-90 in Pilgrimage, “maybe the dust of Abraham Lincoln” should be added to that list.

Deservedly so, Lebovitz’s genius and artistic talent are widely known. But when most people hear the name Anthony Berger, do images of anyone, let alone Lincoln, spring to their minds? Do they realize that most, if not all, of the images of Lincoln branded into their memories from his visage on U.S. stamps, coins, currency, and countless books and advertisements were derived from Anthony Berger’s photographs? The unfortunate answer to both questions is “most certainly not.”

“When Mathew Brady and Anthony Berger first looked at the … photographs that were taken at the Brady studio that February afternoon in 1864, they surely had no idea what they had actually created. They could not have realized the countless different ways in which the images were to be used or the enormous impact they would have. But it is thanks to these images … that the face of Lincoln is better known to Americans today than it was in his lifetime.”[xviii]

Ms. Leibovitz’s picture of Anthony Berger’s photographic negative gives me hope that the time finally has come, 150 years after the fact, for us to collectively tip our hats in recognition of the brilliance of Anthony Berger and Francis B. Carpenter for so artfully collecting “the dust” of Lincoln on several glass plates.

I encourage anyone intrigued by these sentiments to make their own pilgrimage to Anthony Berger’s Lincoln images by viewing them online in high resolution at the National Archives and the Library of Congress. See, e.g., http://www.loc.gov/pictures/search/?q=lincoln%20anthony%20berger. I also highly recommend Ms. Leibovitz’s book Pilgrimage and the current and future exhibitions associated with that book.

By Craig Heberton, July 26, 2014, © 2014

To read an interesting story about the struggle to save tangible historical objects in a digital world, see Jessica Bennett’s “Inside The New York Times Photo Morgue, a Possible New Life for Print” (May 7, 2012) at: http://www.wnyc.org/story/206643-wnyc-tumblr/

“To hold a newspaper in your hand that your great grandmother … might have read, especially in a world that is today so focused on speed, there is something very human and visceral about it.”

—————-

Update on October 27, 2014:

Here’s another example of how knowing the history of an otherwise ordinary looking object completely changes its meaning: http://video.pbs.org/video/2365332583/

—————–

Update on November 30, 2014:

“10 Questions for Annie Leibovitz;” Ms. Leibovitz answers ten head-on questions posed to her by intervewer Sarah Luscombe on behalf of Time.com subscribers — http://content.time.com/time/video/player/0,32068,3335573001_1862545,00.html

—————————————————————–

Update on January 6, 2015:

Read how one man’s “stuff” left sitting untouched in a room for nearly a century presents us with a real time capsule looking back to a life sacrificed in World War I and how things once were.

—————————————————————–

[i] Boxer, Sarah, “Annie Leibovitz’s Ghosts,” The New Yorker, March 19, 2012.

[ii] Browning, Dominque, “A Pilgrim’s Progress,” The New York Times, October 30, 2011.

[iii] “Brady had a special process for copying glass or collodion negatives so that the duplicate plate could not be distinguished from the original.” Ostendorf, Lloyd and Hamilton, Charles, Lincoln in Photographs: An Album of Every Known Pose (1963), at p. 165.

[iv] To view Leibovitz’s photo of the plate in Pilgimage, see: http://www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2011/11/08/pilgrimage-annie-leibovitz/; or http://books.google.com/books?id=xwsLIRIHDj0C&q=berger#v=snippet&q=berger&f=false; or http://victoriacullen.typepad.com/queenwithoutacountry/page/2/.

[v] Boxer, Sarah, “Annie Leibovitz’s Ghosts,” The New Yorker, March 19, 2012

[vi] “The Ghost and Mr. Mumler,” American History Magazine, February 8, 2008. http://www.historynet.com/the-ghost-and-mr-mumler.htm; Moye, David, “William H. Mumler, Spirit Photographs, Amazed Audiences with Ghostly Images,” The Huffington Post, August 22, 2013. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/08/22/spirit-photographs-_n_3795717.html.

[vii] To see some of her photographs, visit http://rogerjnorton.com/photos/marytoddgallery.html.

[viii] Boxer, Sarah, “Annie Leibovitz’s Ghosts,” The New Yorker, March 19, 2012

[ix] Holzer, Harold, Borritt, Gabor S., and Neely, Mark E., “Francis Bicknell Carpenter (1830-1900): Painter of Abraham Lincoln and His Circle,” American Art Journal, at p. 87, fn 2, quoting Carpenter, Francis B., “Personal Impressions of Mr. Lincoln,” New York Independent, April 27, 1865, p. 1.

[x] An image of the painting can be seen at Holzer, Harold, Borritt, Gabor S., and Neely, Mark E., “Francis Bicknell Carpenter (1830-1900): Painter of Abraham Lincoln and His Circle,” American Art Journal, at p. 87. Interestingly, the relative positioning of Lincoln and Tad was swapped in this and Carpenter’s other painting, as if the underlying photograph was horizontally flipped. The part in Lincoln’s hair in the painting, on the left side of his head, is different than the way it is depicted in all of his February 9, 1864 photos, on the right side of his head. This was an anomaly, in that Lincoln’s part otherwise is on the left side of his head in all other photographs. Carpenter wrote on the back of a cabinet-sized print of the Berger photograph used as the basis for the old U.S. $5 bill: ‘From a negative made in 1864, by A. Berger, partner of M.B. Brady, at Brady Gallery ….[Lincoln’s] barber by mistake this day [February 9, 1864] for some unaccountable reason, parted his hair on the President’s right side, instead of his left.” Ostendorf, Lloyd and Hamilton, Charles, Lincoln in Photographs: An Album of Every Known Pose (1963), at p. 177. This language also was quoted by Carpenter’s grandson and then owner of the cabinet card sized print, Emerson Carpenter Ives, in a letter to the editor, published in Life Magazine, March 7, 1955.

[xi] http://peerintothepast.tumblr.com/post/65008148133/abraham-lincoln-by-smithsonian-institution-on. Ostendorf, Lloyd and Hamilton, Charles, Lincoln in Photographs: An Album of Every Known Pose (1963), at pp. 128-129.

[xii] Carpenter wrote in his diary on February 23, 1864, “Found that Berger at Brady’s had made a picture of Mr. Stanton in the position I told him to put him in …” Ostendorf, Lloyd and Hamilton, Charles, Lincoln in Photographs: An Album of Every Known Pose (1963), at p. 186. In Diary of Gideon Welles: Secretary of the Navy Under Lincoln and Johnson, Volume I (1911), at p. 527, Welles writes that on February 17, 1864 he went to Brady’s studio “with Mr. Carpenter, an artist, to have a photograph taken. Mr. C. is to paint an historical picture of the President and Cabinet at the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation.” Although no mention was made of whether Berger was the photographer, it is likely that he was.

[xiii] To see the sketch of Stanton which Francis B. Carpenter presumably completed from Berger’s photograph, as well as several other figure studies sketched by Carpenter of Lincoln’s cabinet members, see Holzer, Harold, Borritt, Gabor S., and Neely, Mark E., “Francis Bicknell Carpenter (1830-1900): Painter of Abraham Lincoln and His Circle,” American Art Journal, at pp. 72-73.

[xiv] Holzer, Harold, Borritt, Gabor S., and Neely, Mark E., “Francis Bicknell Carpenter (1830-1900): Painter of Abraham Lincoln and His Circle,” American Art Journal, at p. 67.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Fisher, David H., Liberty and Freedom: A Visual History of America’s Founding Ideas (2004), at p. 347.

[xvii] Boxer, Sarah, “Annie Leibovitz’s Ghosts,” The New Yorker, March 19, 2012.

[xviii] Sullivan, George, Picturing Lincoln: Famous Photographs that Popularized the President (2000), at p. 82.

Recent Comments