On May 9, 1865, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle announced that “Mr. A. Berger will conduct” a photographic business at 285 Fulton Street in Brooklyn, NY:

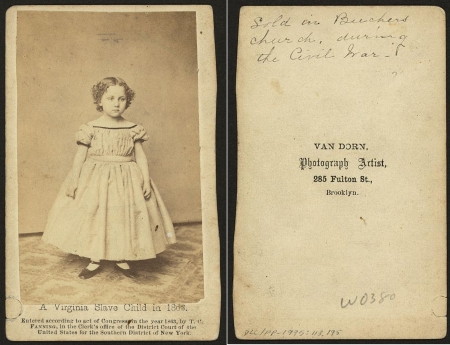

This was not to be the first photographic gallery at that location. The Brooklyn City Directory for May 1863 to May 1864 shows the photographer George Vandorn/Van Dorn at 285 Fulton Street. An example of a carte de visite print with a Van Dorn back mark from 285 Fulton St., follows:

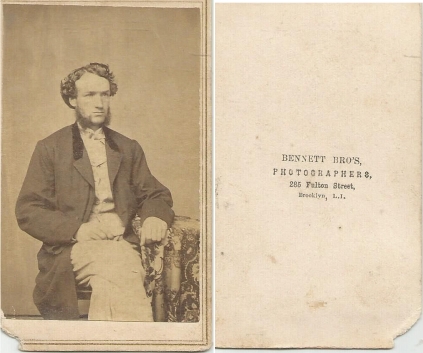

At some point in time, Van Dorn partnered with another photographer, evidenced by carte de visite sized photographs with the back mark “Van Dorn & Bennett, Photographic Artists, No. 285 Fulton St., Brooklyn.” This appears to have represented a transition phase, in that the Brooklyn City Directory for May 1864 to May 1865 lists Van Dorn’s photography business at 314 Fulton Street and the photographers Frank H. & George H. Bennett at 285 Fulton Street, operating as the Bennett Bro’s:

The Bennett Brothers were not the only entrepreneurs doing business at 285 Fulton. A few days before its grand opening, J. Weschler & Co. published notices in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle that it would commence operating at 285 Fulton Street “on or about Monday, February 13, [1865] with an entire new stock of dry goods, cloaks, mantillas, & c., purchased at the recent prices, thus being enabled to offer their stocks at very advantageous terms.” That business soon became known as the dry goods store of Weschler & Abraham. Partners Joseph Weschler and 22 year-old Abraham Abraham each contributed $5,000 to their new venture. The New York Times on May 19, 1865 reported that “the dry goods store [at] No. 285 Fulton-street [Brooklyn], was feloniously enterred [sic] yesterday morning and robbed of silks valued at $998.” Recovering from the theft, Weschler & Abrahm eventually moved elsewhere on Fulton Street and was succeeded by Abraham & Straus in 1893, which became a part of the Federated Stores in 1929, and then merged into Macy’s in 1995.

The Weschler & Abraham store at 285 Fulton was only 25 feet by 90 feet in a multi-story building on Brooklyn Height’s main commercial thoroughfare. In February of 1865, Hunter’s Commercial Academy published notices that it had removed from 285 Fulton Street to a new space on Montague Street. Simultaneously, Weschler & Abraham advertised that it had available to let “a large front room, on first floor, suitable for business; also second floor for dwelling, at 285 Fulton street; Inquiries in the store.”

Anthony Berger undoubtedly took over the former Van Dorn/Bennett Brothers photography studio space. Perhaps, too, he sublet from Weschler & Abraham and purchased some or all of the Bennett Brothers’ equipment and supplies. A one-third page advertisement for Berger’s business in the 1865-66 Brooklyn City Directory, appears below:

From all of this it can be inferred that Berger’s split with Mathew Brady and move to Brooklyn did not occur until the spring of 1865 — around the time that President Lincoln was shot in the back of the head by John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. on April 14, 1865.

Then I Can Make It, (Almost) Anywhere

Why did Berger choose Brooklyn? As mentioned in Part I of “Chewing on A. Berger,” there is evidence in the 1855 New York State Census that Anthony Berger and his family may have lived in Brooklyn shortly after he first arrived in America. If true, he would have been familiar with that city and possibly a number of its inhabitants, especially resident artists such as Francis Bicknell Carpenter. It was Carpenter who arranged for and oversaw Berger’s three photo shoots with President Lincoln. Also, at the start of the Civil War, the 1860 U.S. Census shows that Brooklyn was the 3rd most populous city in the U.S., with over 266,000 inhabitants, situated a short ferry ride away from America’s largest city and its 813,000 residents. In a sense, Brooklyn Heights, where Berger operated, was Manhattan’s first commuter suburb. Anthony Berger likely perceived that Brooklyn offered more favorable commercial and artistic opportunities than a place like Manhattan, where the competition included internationally renowned photographic heavyweights such as Brady, Gurney, Bogardus, Fredericks, Sarony, and the Anthonys. Although there was plenty of competition in Brooklyn, Berger may have felt that he stood a better chance of making a go of it there both as a professional photographer and a painter.

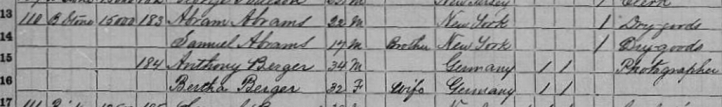

How did Berger wind up at 285 Fulton Street in Brooklyn? As revealed in the 1865 New York State Census returns, as of June 19, 1865 Anthony Berger (aged 34) and his wife resided in the 4th ward of Brooklyn in a brownstone residence owned by a Weschler & Abrahm partner — Abraham Abraham (listed therein as 22 year-old dry goods merchant “Abram Abrams” — see below).

This suggests two things. First, the Bergers probably were in a temporary living situation and had only recently moved to Brooklyn. Second, there existed some sort of pre-existing relationship or connection between the Bergers and the Abrahams which resulted in Anthony Berger leasing space at 285 Fulton St. and presumably residing on a temporary basis with Abraham Abraham and his 17 year-old younger brother Samuel. The common thread may have been that the Abrahams were sons of a Bavarian merchant. Perhaps, too, the Bergers were Jewish like the Abrahams.

Mourning “Father Abraham” in Pictures

The short announcement in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of the opening of Anthony Berger’s business was silent on Berger’s prior association with M.B. Brady. Instead, it focused upon the newspaper’s receipt of a retouched version of what was becoming a wildly popular and repeatedly plagiarized photograph taken by Anthony Berger of the recently martyred President in Brady’s Washington studio on February 9, 1864.

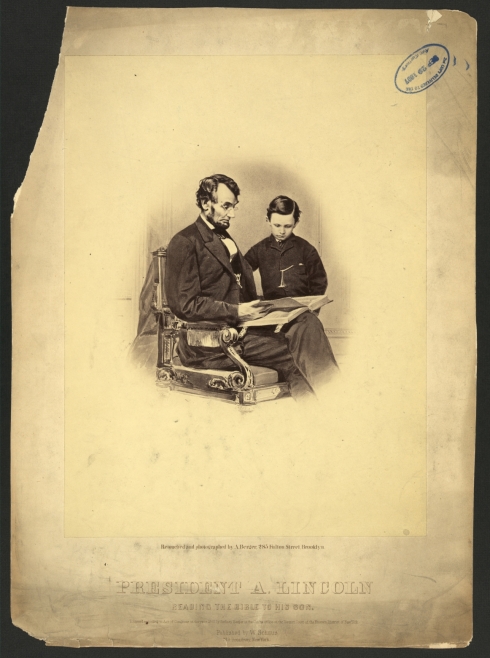

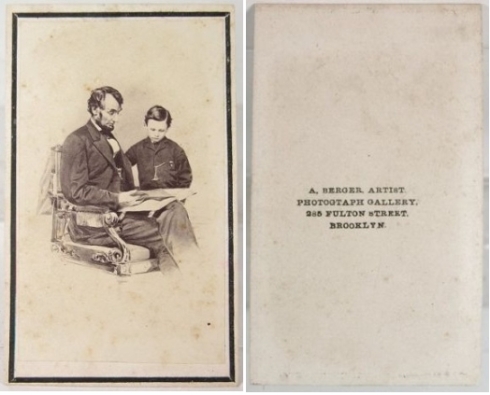

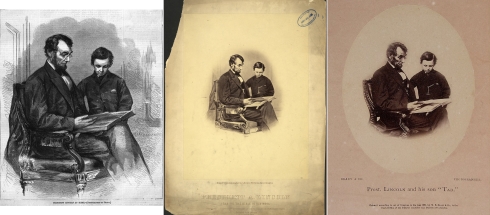

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’s description of the image was wrong on two counts; in actuality, the underlying photograph reveals a seated Lincoln peering at a Brady studio photo album (not a Bible) with his youngest son Tad (the middle son, Willie, had died in 1862). The paper’s source for the first mistake was Anthony Berger. Lloyd Ostendorf reveals that Lincoln expressed misgivings to his friend/journalist Noah Brooks that the large photo album with brass clasps might be mistaken for a Bible and that it only came to be used in the photo session when the photographer [Anthony Berger] “hit upon [it] as a good device … to bring the two sitters [father and son] together.” Having personally placed into Lincoln’s hands an album from the Brady studio to use as a prop, Berger knew full well that it was not a Bible. Nevertheless, he titled a retouched version of his own photograph as “PRESIDENT A. LINCOLN READING THE BIBLE TO HIS SON,” had it created in a large format by the high-end New York City printer William Schaus, and copyrighted it in 1865 (see, below, courtesy of the Library of Congress). The full caption reads:

“Retouched and photographed by A. Berger, 285 Fulton Street, Brooklyn – PRESIDENT A. LINCOLN READING THE BIBLE TO HIS SON – Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1865 by Anthony Berger in the Clerks [sic] office of the District Court of the Eastern District of New York.”

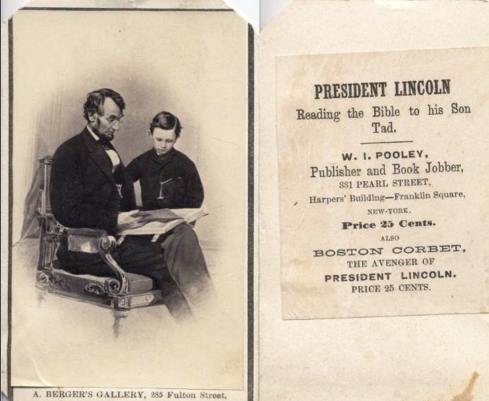

Berger’s emotionally stirring picture of Lincoln, posed to appear as if the President was enjoying a “family moment” with his youngest son, tugged upon the most sentimental heartstrings of Northerners. Many must have felt an irresistible urge to acquire a calling card sized rendering of that image (called a carte de visite) of the martyred “Father Abraham” for insertion into their cherished family photo album. Two carte de visite prints of Berger’s retouched photograph of President Lincoln & Tad appear below (top, courtesy of Walnutts Antiques – Walnutts on eBay, and bottom, courtesy of bandj.images on eBay):

According to Lloyd Ostendorf, the incentive to profit from the heavy demand for this keepsake also was great:

“it was “one of the most popular Lincoln portraits [and] it is the only close-up of him wearing spectacles. It was issued in huge quantities in many variations, with and without Brady’s permission.”

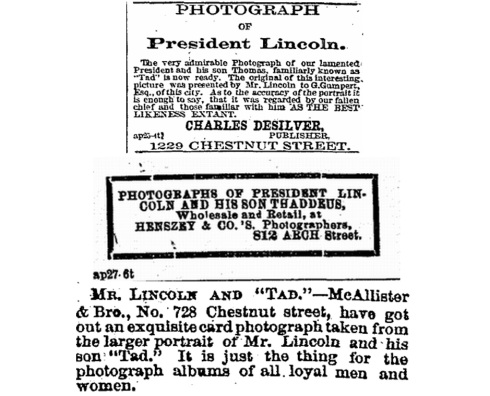

The copyright laws then existing did not yet explicitly prohibit photographing someone else’s work, retouching features of it on a duplicate negative, printing copies of the altered original image, and then selling them in one’s own name with impunity. Copyright laws had not yet caught up with the reproductive powers of photography. Thus, printers and photographers quickly seized on the image’s popularity after Lincoln’s death and sought to cash in. See, for example, three different Philadelphia newspaper advertisements — one calling it “just the thing for the photograph albums of all loyal men and women” — which appeared in the April 28, 1865 Daily Evening Bulletin (top), the April 28, 1865 Philadelphia Press (middle), and the April 29, 1865 Daily Evening Bulletin (bottom):

Brady, likewise, didn’t miss out on selling prints of the father-son photograph taken by Anthony Berger and Harper’s Weekly used it as the basis for a cover illustration a few weeks after Lincoln’s assassination. A print of what the Brooklyn Daily Eagle described as Anthony Berger’s “India Ink drawing” appears below (middle) sandwiched between a Harper’s Weekly May 6, 1865 cover illustration (below, left) and an unretouched print by “Brady & Co.” (below, right). Harper’s, by the way, notated that its illustration was “Photographed by Brady.”

The most obvious revisions made by Anthony Berger to the original photographic image are: (1) seating Lincoln in a straight-backed chair with a flowing jacket or piece of cloth draped from its back, (2) fancy fringe hanging from the chair’s arm, (3) subtle alterations to the photo album making it appear to be a Bible, and (4) recasting the setting to resemble a room in the White House. Note, also, how the Harper’s Weekly illustration looks very similar to Berger’s retouched version in many respects despite its attribution to Brady. A major exception is that Harper’s Weekly did not depict the chair with a ramrod straight back, sticking, instead, to a tilted back more closely resembling the actual chair’s appearance.

Why did Berger alter the chair, let alone do so to such a degree? The simple answer probably is that the chair in which Lincoln sat was a very widely recognized prop in Brady’s Washington gallery, having been given by Lincoln to Mathew Brady in 1860 after Lincoln’s Cooper Union speech. It had served as Abraham Lincoln’s chair in the House of Representatives and, therefore, was of a size sufficient to comfortably accommodate Lincoln’s frame. Brady and his operators also photographed many other famous people who posed in the Washington gallery seated in that very same chair, including luminaries ranging from Walt Whitman to Robert E. Lee.

If the Harper’s illustrators based their work exclusively on a print provided by Brady’s gallery, then Berger presumably altered or oversaw the retouching of the original image when employed by Brady — possibly making more than one variant form — and upon his departure took with him a duplicate plate of his handiwork. In which case, Harper’s Weekly could have based its illustration exclusively upon a Berger retouched version submitted by Brady. Although it is at first counterintuitive to think that Brady would have submitted a variant of the original photo touched up in a manner to obliterate his trademark “Brady Lincoln chair,” he may have desired simply to create the illusion that the photo was taken in the White House by altering the chair and the surroundings. Many discerning people who had been in his D.C. gallery conceivably would have recognized the chair as a studio prop, undercutting the desired effect. Thus, Harper’s might have received the retouched work from someone at Brady’s a week or two before the printing of its May 9, 1865 issue when Berger still may have worked for Brady. But what if Berger left Brady months before Lincoln’s assassination? Did Harper’s Weekly combine elements from both a print of the original photograph and a version copyrighted in Berger’s own name, relying most heavily upon Berger’s variation despite crediting Brady? Regardless of the correct answer to these questions, one way or the other, the Harper’s Weekly illustration was based on a photo taken by Berger on February 9, 1864 and likely retouched by Berger, either before or after he left Brady.

[Note: Harper’s Weekly posted a clarification in its May 13, 1865 publication that the “Portrait of Mr. Lincoln at Home” on the cover of its May 6, 1865 issue, was “copied from the admirable Photograph of Mr. A. Berger, 285 Fulton Street, Brooklyn.” This attribution to Anthony Berger, coming a week late and buried in a back page, symbolized the shadow of anonymity under which Berger had operated during his course of employment with Brady.]

Parting Company with Mathew Brady

Whatever precipitated the end of Anthony Berger’s employment with Brady might have resulted from a deal which Brady struck in September of 1864 (as discussed below). But it can be supposed, too, that factors contributing to the Brady-Berger schism paralleled Philip Kunhardt’s and Dorothy Meserve Kunhardt’s explanation for why another cameraman parted company with Brady:

“Brady was often unable to support operations in the field … David Woodbury, a young photographer who greatly admired Brady and worked diligently for him through most of the war [nevertheless was] all but abandoned [when Brady failed] to send him the supplies he required. Woodbury, like other of Brady’s battlefield photographers, finally quit in frustration and disgust.” — Sullivan, George, Mathew Brady: His Life and Photographs (1994), at p. 105.

Berger, likewise, may have been owed unpaid wages and/or unreimbursed field expenses by Brady. For example, Andrew Burgess, who also worked for Brady in Washington appears to have retained some duplicate Brady glass plate slides as compensation for unpaid wages. By 1874 he even felt entitled to advertise his photography business as a “successor” to Brady’s from the same Pennsylvania Avenue location which Brady later was forced by his creditors to close in 1872. Ironically, those glass plate negatives ultimately came to be owned by the Ansco Co., which claimed them as compensation for debts unpaid by Brady to Ansco’s predecessor, E.H. & T. Anthony & Co. Today they are part of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery collection.

Alexander Gardner — who like Berger had managed Brady’s Washington gallery — may have been the first to establish the “tradition” of gathering up and departing with all accessible duplicate plates of one’s own work when separating from Brady.

“When Gardner left Brady’s studio he took all the negatives from the year 1862 with him, including [the work of O’Sullivan, Barnard, and Gibson] — more than four hundred negatives in all … [T]hey certainly had been copied [and] O’Sullivan, Barnard, and Gibson soon went to work for Gardner in his new gallery.” Robert Wilson, Mathew Brady: Portraits of a Nation, at p. 148.

Add to this cauldron of potential disgruntlement the inescapable conclusion that Anthony Berger must have been relieved of his position as manager of Brady’s Washington, D.C. gallery sometime shortly after September 7, 1864 when a presumably cash-strapped Mathew Brady sold a 50 percent stake in his Washington, D.C. gallery to James F. Gibson for $10,000, half in cash and the other half in promissory notes (according to Josephine Cobb). After becoming an equal partner in the D.C. gallery, Gibson — a former Brady photographer who had worked for Alexander Gardner after leaving Brady — surely took over the reins of managing the Washington gallery’s day-to-day operations, thereby displacing Berger as its manager. Josephine Cobb described James F. Gibson as “a good photographer but a man lacking business ability and personal integrity.” Her research shows that Brady had brought Berger in as the D.C. manager to oversee Gibson sometime in 1863 before Gibson defected to Alexander Gardner. In September 1864, Gibson had the opportunity to return the favor in a reversal of roles. Berger must have found the position into which he was placed in the fall of 1864 untenable. Was Berger then demoted to a level under Gibson in D.C., reassigned back to New York, fired, or simply packed his bags and quit? If he parted ways with Brady in September of 1864, where did he go and what did he do between then and May of 1865?

By Craig Heberton, July 15, 2014 (To be continued)

Sooooo….??? What happened to Anthony Berger AFTER all of this? Very curious! 🙂

I intend to tell the rest of the story of Anthony Berger either in a book or article in the future!