Whenever I read of a newly discovered photograph of a famous historical figure or the image of a legendary name hidden in a well known old photograph, my attention is grabbed. After which, my next usual impulse is to evaluate whether the discovery is for real.

For a few moments the other day, my attention was grabbed.

I happened to review a positive digital image of a photographic plate at the National Archives labeled 111-B-5152. You can see it here at: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/529258?q=111-B-5152. The photograph clearly was taken in the Washington, D.C. studio of Mathew B. Brady.

At first blush, the image was of no special interest to me. It is titled “Gen. Francis Preston Blair, Jr. and staff of fifteen” by the National Archives. Although undated, the photo clearly was shot sometime after November 1862 when Blair was promoted to Major General. A second star insignia on Blair’s right shoulder strap is barely visible, denoting his rank.

The Blair House of Politics

A Princeton College graduate, Blair was born in Lexington, KY in 1821 and engaged in politics in Missouri after establishing his legal practice in St. Louis. He became a dominant Republican in his home state and oversaw efforts to elect Lincoln in 1860 because, among other things, Blair was opposed to the further expansion of slavery. He also served several terms in the U.S. House of Representatives before and during the Civil War. He is “credited with being the principal leader in saving Missouri for the Union in 1861.”[i] His father, Francis Preston Blair, Sr. was a mover-and-shaker in the creation of the Republican Party in 1854 (Hal Holbrook portrayed his father in Steven Spielberg’s movie Lincoln (2012)). His parents’ home in Washington, D.C. is still known as the Blair House and has served as the President’s Guest House since the U.S. government bought it during World War II. Francis P. Blair, Jr.’s brother Montgomery Blair, served as Postmaster-General in Lincoln’s cabinet for several years. Thus, at the time of the Civil War, the Blairs, perhaps, were as prominent and powerful of a political family as existed.

Francis Preston Blair, Jr.’s distinguished military service during the Civil War — including at Vicksburg, Chattanooga, and under Gen. Sherman in the “March to the Sea” — only made him more popular before the war’s end. [ii] Ulysses S. Grant wrote this about Frank Blair in July 1861: “There was no man braver than he, nor was there any who obeyed all orders of his superior in rank with more unquestioning alacrity.”[iii]

“Or I’ll Eat My …“

Scanning the National Archive’s image, something in the foreground along the left-hand margin caught my attention. “Is there someone lurking in the shadows?,” I blurted out loud to no one in particular. Zooming in, I saw the nearly all-white profile of a face and part of an upper torso. Its appearance led me to conclude that it must be a sculpted bust resting on a pedestal … and that it looked like Abraham Lincoln (detail, below, of the apparent bust).

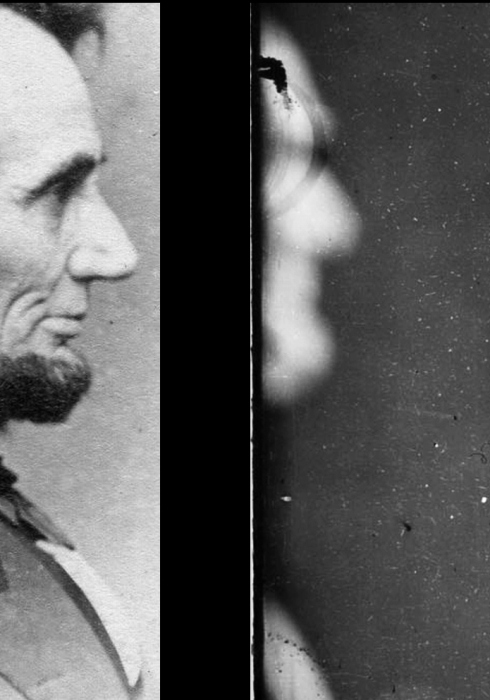

Comparing Lincoln’s profile in a photo taken by Anthony Berger in Brady’s Washington studio on February 9, 1864 to the fuzzy & out-of-focus profile in 111-B-5152, revealed the following:

So then I wondered, “is there any possibility that this might be Lincoln himself?” Lincoln visited Brady’s studio on several occasions during his presidency. Surely it was possible that Lincoln might have visited the studio on the same day that Brady’s studio manager, Anthony Berger, was creating photographs of the president’s political ally, Major General Frank P. Blair, Jr., of the powerful conservative faction of the Republican Party? Might Lincoln have arrived early, peeked in on Blair, placed his fidgety right arm and hand atop a pedestal, and accidentally photo-bombed the last seconds of a photo shoot? Reaching my own conclusions, I nevertheless decided to turn to several Civil War photo enthusiasts for their input. In a cover message, I wrote:

“assuming its Lincoln’s profile, is it a bust or the real man? I’m not sure. But to me it looks possible that there is an arm with a fidgety hand perched on the pedestal. Not quite sure what the white blob is. So I cannot say it is definitively a bust.”

The first gentleman to respond proclaimed — ” Well that’s damned interesting! … I’m speechless (for now).” Three hours later he wrote:

“Here’s what I see. Abraham Lincoln is standing behind an open door to Brady’s studio … He’s holding a book in his right hand. The binding is facing in our direction. The object overlaying the book is Lincoln’s right hand, which is moving in front of the door’s brass door knob. The President has just entered the room unannounced, as the exposure finished up … If this were a bust, we’d see the table on which it must sit. The bright object seen below the visible portion of Lincoln’s shirt may be his watch.”

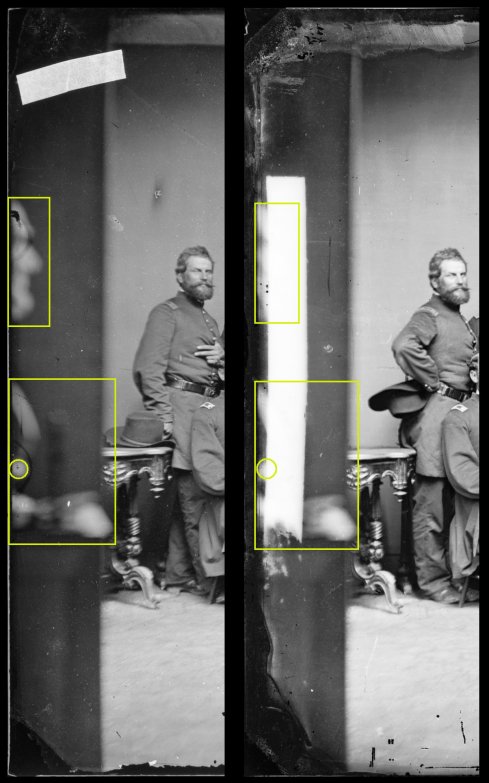

But soon he messaged the group that he had found a variant view of General Blair posing at Brady’s studio with the same men within the Library of Congress’ collection, identified as LC-BH831- 575 (see below), and added — ” if this is not Lincoln’s distinctive profile, I’ll eat my (fill in the blank).” Oh!,” I exclaimed, as I wondered out loud what object he would consume if we were to conclude it wasn’t Lincoln’s profile — perhaps a stove pipe hat?

The variant view clearly shows Gen. Blair and his staff posing at Brady’s studio on the same day. In fact the camera position and the space framed is identical. But that view doesn’t seem to show the Lincoln-appearing white image in profile on the extreme left edge of the plate. This observation caused some more preliminary “thinking out loud” speculation in support of the supposition that President Lincoln may have photo-bombed 111-B-5152.

Yet the discovery of the variant LC-BH831- 575 view ultimately helped the group answer my initial question, but only after we navigated through several other prickly minefields.

For starters, another Civil War photography expert asked, “seriously if that is Lincoln [in the flesh] wouldn’t his beard be dark?” I wrote in reply that perhaps his face and dark hair and beard were all washed out because we were seeing a “ghost image” caused by movement during the course of a multi-second studio exposure, enhanced by the face being out of focus and in bright, direct sunlight from an unseen skylight above. Maybe it was possible that Lincoln had moved partially into view only at the tail-end of the exposure. The more a person moved, the more their features could be distorted in a wet-plate collodion exposure. Also, the shorter the time period one appeared in an several second exposure (which may have reached something like ten seconds in Brady’s studio), the more washed out their image might appear (examples, below — “Ghost image” of a (twinned) boy in motion at Gettysburg’s Soldiers’ Cemetery, November 19, 1863, from LC-B815- 1159; a boy outside Castle Thunder, Richmond, Va., April 1865, from LC-B811- 3362):

But the problem of interpreting much of what is seen on the extreme left side of the 111-B-5152 and explaining why it differed from the same area in LC-BH831- 575 remained unanswered. Moreover, a quick search didn’t yield the same Lincoln-like profile, let alone a bust of Lincoln, in any other Brady studio photos, again hinting that what appeared in the left-hand margin of 111-B-5152 might be someone’s fleeting appearance and not a bust perched in Brady’s studio. Ultimately, however, the ” I’ll eat my (fill in the blank)” researcher soon noted something which had also dawned upon me.

He realized that a piece of tape placed on the negative plate for LC-BH831- 575 had prevented us from recognizing that the extreme left of LC-BH831- 575 almost certainly was identical to the same area in 111-B-5152. What I initially thought was a highly illuminated area in LC-BH831- 575 had resulted from someone covering the plate with tape which made that area look white after the plate was scanned and the negative was turned into a positive image (see detail below, right). In fact, on our first pass we had failed to notice a much smaller piece of tape placed in the upper left-hand corner of 111-B-5152 which produced the same effect (see detail below, left). A side-by-side comparison of detail within 111-B-5152 and LC-BH831- 575 reveals that if we could remove the tape from LC-BH831- 575’s plate, what apparently is Lincoln’s bust would be visible in it too:

The apparent bust of Lincoln, moreover, probably was on a pedestal or table behind what was likely a screen and hadn’t moved at all between the shooting of the two photos (which could have been several minutes apart because of the long prep time needed to prepare a glass plate negative for use). Our intrepid “I’ll eat my …” researcher determined that the bust likely was a form of “Parian Ware,” a process, he explained, “of mass producing statuary, designed to imitate carved marble … a fellow called Martin Milmore apparently was on the cutting edge of [producing this] around the time of our Gen. Blair group shot. It’s not unreasonable to think that Brady might have owned one of Milmore’s Lincoln busts, which he produced and signed. Christies sold one in 2009 for $4,750.” The same gentleman created the following marked interpretation of 111-B-5152:

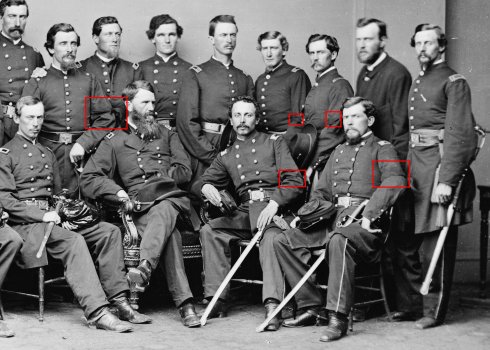

Other clues revealed a possible date for when the photographs were taken. They are:

- The officer in the top row, second from the left, apparently could no longer button his coat;

- The presumed officer in the top row, second from the right, was out of uniform; and

- A few of the officers are wearing a black or dark mourning ribbon or band tied on their left arms (marked, below).

These clues suggest that the Civil War was over (at least the Appomattox Courthouse surrender had occurred) and Lincoln had been assassinated. Many soldiers presumably wore black mourning bands or sashes to mark the murder of their President when Lincoln’s funeral procession passed through Washington, D.C. on April 19, 1865. The Daily National Republican of April 17, 1865 reported that Secretary Stanton had ordered the military to wear the badge of mourning on the left arm. The same symbol of mourning and remembrance was tied to soldiers’ arms in other cities to which Lincoln’s catafalque traveled, including New York City. See also, https://www.flickr.com/photos/110677094@N05/14977153225/. Some soldiers likely chose to wear those arm bands during the Grand Review of the Union Army which occurred in Washington, D.C. on May 23-24, 1865. Although there are reports in the historical record that the city of Washington no longer was in formal mourning for Lincoln as of the time of the Grand Review of the Union Army, some photos show flags at half mast and specific buildings decked out in black mourning crepe (e.g., LC-B8184-7748, below, captioned “Washington, D.C. Spectators at side of the Capitol, which is hung with crepe and has flag at half-mast during the ‘grand review’ of the Union Army”). In Proclamation No. 129, President Johnson declared May 25, 1865 to be “a day of humiliation and mourning” for Lincoln but later postponed that date until June 1st.

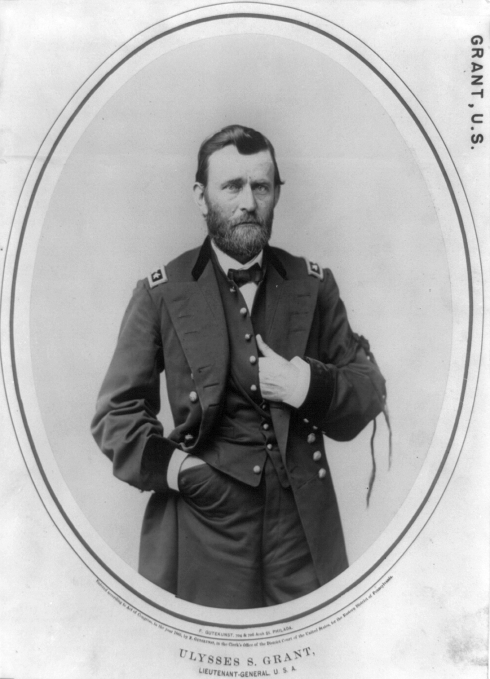

Gen. Blair and his officers, as members of Sherman’s Army, would have participated in the Grand Review on May 24. This may explain why they were all gathered together in the nation’s capitol, that some wore mourning bands during the photo session, and their boots were outfitted with spurs for riding possibly in the procession. See below, for example, LC-USZ62-1770, an 1865 copyrighted image of General Ulysses S. Grant posing for Frederick Gutekunst while wearing a mourning sash tied onto his left arm said to be in honor of President Lincoln (courtesy of the Library of Congress).

Thus, the date of the photo session may have been on or about May 23, 24, or 25, 1865, near the time that Blair and his staff rode in the Grand Review and when the nation still collectively mourned for Abraham Lincoln.

We don’t know to whom the apparent bust of Lincoln belonged or why it was placed where it would appear in the outer fringes of the negative. Perhaps the bust wasn’t a fixture in the Brady studio and General Blair had recently purchased it. If so, I’d like to think that the General desired to take it back home with him to better remember his fallen commander-in-chief.

So in about 24 hours, our little group concluded that a bust of Lincoln probably had made two unexpected appearances in Brady studio photographs. Not quite on par with spotting a new photographic image of Abraham Lincoln in the flesh-and-blood, but a very cool “profile of Lincoln” discovery, nonetheless.

Unless someone else shows us to the contrary within the next 24 hours, no stove-pipe hats will be eaten.

by Craig Heberton IV, July 5, 2015

———————————————————————————————————-

[i] William E. Parrish, Frank Blair: Lincoln’s Conservative (1998) (dust cover)

[ii] http://www.civilwarmo.org/educators/resources/info-sheets/francis-preston-blair-jr; http://history.house.gov/People/Listing/B/BLAIR,-Francis-Preston,-Jr–(B000523)/ http://www.mrlincolnswhitehouse.org/inside.asp?ID=129&subjectID=2; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Preston_Blair,_Jr.

[iii] Parrish, Frank Blair: Lincoln’s Conservative (1998), at p. 174.

![LC-BH831- 575 03120a[0]](https://abrahamlincolnatgettysburg.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/lc-bh831-575-03120a01.jpg?w=735&h=585)

![LC-BH831- 575_stuff[1]](https://abrahamlincolnatgettysburg.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/lc-bh831-575_stuff1.jpg?w=490&h=551)

Recent Comments