Imagine yourself as a young male schoolteacher in Pennsylvania about 150 years ago.

You have been invited to attend the Thirteenth Annual Session of the Pennsylvania State Teachers’ Association in Gettysburg from July 31st to August 2nd, 1866.[1] President Lincoln’s assassination and the end of four unfathomably bloody and numbing years of war are only a few months removed in time. You have returned home from two years of military service but minus some family members, soldier colleagues, and friends. Though the gruesome and glorious events of 1861-1865 are forever etched in your memory, your job now, as it was for several months before you enlisted, is to educate schoolchildren.[2]

The chance to see the famous Gettysburg battlefield is irresistible. While the battle raged there, you served in the 45th Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment under the cousin of Pennsylvania Governor Curtin at the assault on Vicksburg.[3] That Vicksburg and several other battles in which you participated never attained the fame of Gettysburg is still beyond your comprehension. For that reason, you want to see Gettysburg. Because the Pennsylvania State Teachers’ Association has arranged for free rail fare, you have no excuse not to go.

You arrive in Gettysburg on the afternoon of July 30, 1866 at the same rail station from which wounded soldiers were borne off to hospitals back east only three years ago; you also make a mental note that President Lincoln and other famous American and foreign dignitaries passed through the same station. At the Gettysburg Courthouse you register for the event by paying an annual fee of $1.00. There you encounter the President of the State Teachers’ Association, Dr. S.P. Bates, who asks you to act as a scrivener for the Session meetings and serve as the chronicler of arranged Gettysburg battlefield visits. He explains that if you agree, you will be asked to compose a written account for the September 1866 edition of the Pennsylvania School Journal. He knows of your stenography and writing skills and offers to pay you a nominal sum for your services. You are honored by the request and immediately consent.

The opening speaker at the Association’s morning session on July 31, 1866 is Dr. Bates. He explains how an unexpectedly large turnout forced the relocation of the session meetings from the Court House to St. James Lutheran Church on York St. You wonder to yourself how the Association was caught unawares by the large turnout — why didn’t they anticipate that so many teachers would want to see the Gettysburg battlefield? You are pleased to learn that “arrangements [will] be made for a visit to the battle-field by members present, with suitable guides [so as not to] interfere with the regular session …” Dr. Bates further expresses the hope that joining together on the “great and decisive battle-field” of Gettysburg where …

“many of the soldiers here were teachers … should incite us to still greater efforts. Our schools, academics and colleges were preserved by this victory; but we should not be satisfied with this result. The cause of Education, thus preserved, must also be made progressive or rather aggressive … The future condition of [especially the Southern States] will greatly depend upon the use now to be made, by the art of the teacher, of the advantages thus conquered for its children.”[4]

The County Superintendent of Schools for Adams County, Pa., Mr. Aaron Shelley, speaks next. He had been a teacher before his first election to the post of county superintendent in 1863[5]. After welcoming us to Gettysburg, he explains that …

“there are those present who participated in the sanguinary conflict here, and to them I must leave the task of describing more fully the scene and events which have made Gettysburg so celebrated … You will not fail to visit the Soldiers’ National Cemetery and shed a tear over the graves of the gallant dead … It is the soldier’s duty to fight for principles, but it is the teacher’s duty to establish and maintain them … Yours is truly a mission of love and good will.”[6] [emphasis added]

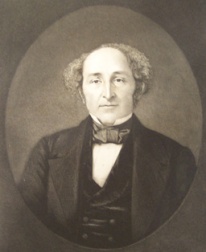

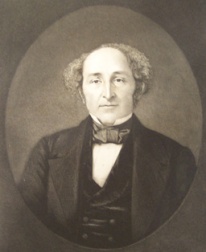

Late in the afternoon, you join a group visiting Pennsylvania College at the invitation of its president, Dr. Henry L. Baugher, who receives you there. A Cincinnati journalist’s description of Dr. Baugher is apt:

“a semi bald head, a hooked Roman nose, clear blue eye, and a decidedly clerical face. He would pass anywhere for a theological professor, a man of firm will, but kindly.”[7]

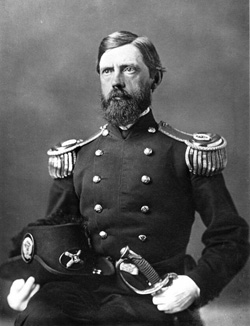

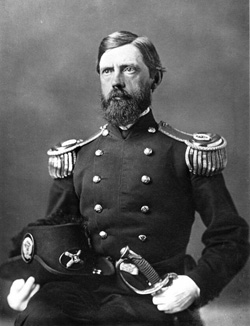

You express your keen interest in seeing the battlefield on Cemetery Hill to Dr. Baugher. He, like Mr. Shelley, graciously explains that you should not fail to pay homage at the Soldiers’ Cemetery and there ponder President Lincoln’s consecration address. Dr. Baugher mentions, too, the role he played in those dedication ceremonies by giving a brief closing benediction after Lincoln’s remarks.[8] You tell him what an honor it must have been to speak the closing prayer at such an auspicious event on hallowed ground with President Lincoln seated just a few feet away. [Dr. Henry Baugher, below, from the Dickinson College Archives]: You then join at least 200 other teachers under the carriage[9] escort of Colonel George Fisher McFarland[10], a teacher and former principal of McAlister Academy in Juniata County, Pa., who lost a leg during the battle’s first day at Gettysburg. It was there that he led the 151st Pennsylvania Regiment (aka the “Schoolteachers Regiment”) to reinforce the Iron Brigade around Herbst Woods. Near there the 151st took up defenses along Willoughby Run. When the entire First Corps fell back, he had his regiment rally at the Lutheran Theological Seminary where he was shot in both legs.[11] By fighting a delaying action, McFarland’s regiment suffered extraordinarily high casualties and losses (337 of 467 men, or about 72%). [Below, left, a pre-Gettysburg photograph of Geo. F. McFarland and detail of his gravestone at Harrisburg Cemetery, both from findagrave.com]:

You then join at least 200 other teachers under the carriage[9] escort of Colonel George Fisher McFarland[10], a teacher and former principal of McAlister Academy in Juniata County, Pa., who lost a leg during the battle’s first day at Gettysburg. It was there that he led the 151st Pennsylvania Regiment (aka the “Schoolteachers Regiment”) to reinforce the Iron Brigade around Herbst Woods. Near there the 151st took up defenses along Willoughby Run. When the entire First Corps fell back, he had his regiment rally at the Lutheran Theological Seminary where he was shot in both legs.[11] By fighting a delaying action, McFarland’s regiment suffered extraordinarily high casualties and losses (337 of 467 men, or about 72%). [Below, left, a pre-Gettysburg photograph of Geo. F. McFarland and detail of his gravestone at Harrisburg Cemetery, both from findagrave.com]:

Wrote General Abner Doubleday:

“At Gettysburg [the 151st Pa Regiment] won, under the brave McFarland, an imperishable fame. They defended the left front of the First Corps against vastly superior numbers; covered its retreat … and enabled me, by their determined resistance, to withdraw the corps in comparative safety … I can never forget the services rendered me by this regiment, directed by the gallantry and genius of McFarland. I believe they saved the First Corps, and were among the chief instruments to save the Army of the Potomac and the country from unimaginable disaster.”[12]

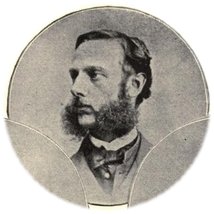

You are honored that the “brave McFarland” proudly leads you and the others in your group to where he understands General Reynolds fell — “the officer whose ‘magnificent rashness’ perhaps assured to us the victory.” Pausing on that ground, he speaks of Reynolds in reverential, almost hushed tones. [John F. Reynolds, pictured below, courtesy of the Library of Congress]:

After narrating “many incidents of the fight” and the first day’s “positions held by the troops at different times in the day,” Col. McFarland escorts your rapt and attentive group to the Lutheran Theological Seminary, also located on the battlefield, and then directs you to enter the building where his leg was amputated at a temporary hospital before the Confederates overran the position and took him prisoner. You think you hear him musing about where his amputated leg might be buried before he speaks with the highest praise for the services rendered by the surgeons and their assistants in that makeshift hospital which at present again functions as a school for higher education.

Thanks to the Colonel, you are beginning to understand the significance of Gettysburg.

Later that evening, Col. McFarland delivered a presentation in which he declared:

“the real issues involved [in the late rebellion] were better understood by the soldiers of the Union army than by those of the Rebel army … whether from the nature of the issues involved, or from other causes, more reason and less passion were exhibited by the soldiers of the Union than the Rebel army … and important differences between [the two armies] were the result of the universal diffusion of knowledge among the masses in the North, and a total want of this diffusion of knowledge amongst the masses in the South … Whole regiments of teachers responded to the calls of President Lincoln for troops, and hundreds sealed their devotion … by shedding their blood in its defence … It was the fortune of the speaker to lead full sixty teachers into battle just west of the Seminary, in the first day’s fight, [many of whom were killed or wounded]. The victory at Gettysburg [,] the work of the teacher! … And may you who have assembled upon this sacred spot to re-burnish your arms for new battles with ignorance and passion, catch the spirit of your worthy co-laborers who met here three years ago …” [emphasis added] [13]

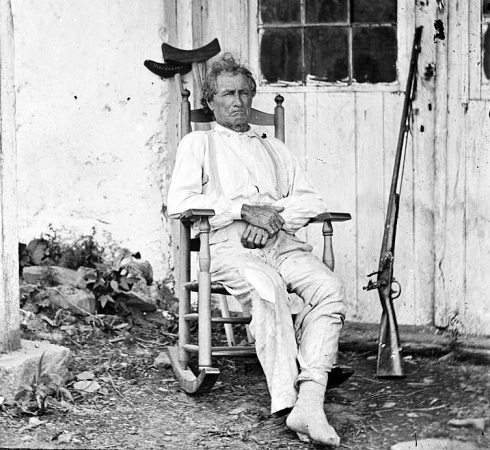

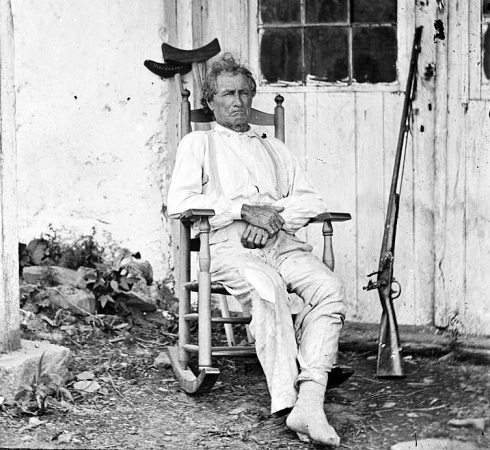

Arising in the darkness early the following day, you depart for a tour of the second and third days’ fighting shortly after 6 a.m. Your guides are Col. McFarland, “the venerable John Burns” (the only citizen of Gettysburg reputed to have taken up arms against the Rebels at Gettysburg), Major Henry Lee, and Captain Walter L. Owens (a music teacher).[14] [John Burns, pictured below, left, in mid-July 1863 in front of his Gettysburg home, posing with a musket, by Mathew Brady photographers, courtesy the Library of Congress; and Capt. Walter L. Owens of the 151st Pa. Regiment, below, right, courtesy of the Gettysburg National Military Park library]:

You all proceed as a singular group to the Soldiers’ Cemetery. From there, you split up and your group follows McFarland, Lee, and Burns to the right for a tour of Culp’s Hill where you are regaled with stories of heroism and observe the projectile-riddled trees and the Union breastwork defenses thrown up at the barb of their fishhook lines. The other even larger group leaves Cemetery Hill and follows Capt. Walter L. Owens[15] to the left on a tour towards the “Round Top.” One of the teachers in the Owens group later relays to you some of what he observed, allowing you to report:

“The evidences of the conflict are still to be seen in many directions. At one place [on the route to the Round Top] we found a human skull …. the farmer informed us that he had turned it up with his plough [but not why it was fixed “upon the top of a paling”]. Most of the stone breastworks on [the left] side, and those of earth and logs on Culp’s Hill still remain as they were left at the close of the great battle, the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association having preserved the ground intact as far as was possible.”

When the tour returns to town before 10 a.m., you thank each of your guides by shaking their hands. Only John Burns eludes your handshake. Your appreciation of the Battle of Gettysburg and some of the town’s unusual and colorful residents has grown even greater. When official Association business resumes, several teachers debate the merits and demerits of coed schooling followed by discourses on the subject of “grammar” during the afternoon session. Then it is time to again visit Cemetery Hill. You write:

“The most interesting episode of the week was the visit to the NATIONAL CEMETERY, on Wednesday evening … after an early tea, the members [of the Association] and many citizens of Gettysburg, who had heard of the proposed visit, betook themselves to Cemetery Hill. About half past six o’clock the assemblage of several hundred was called to order by COL. MCFARLAND …” [emphasis added]

Once upon the grounds of the National Cemetery, you are struck by the beauty of the final resting place for many of the Union soldiers killed at Gettysburg. It is classically simple, elegant, and geometrically curved in design. A poignant resting place with a commanding view.

“After the singing of the Star Spangled Banner, by the Glee Club,” Professor Martin L. Stoever of Gettysburg’s Pennsylvania College ” (pictured below, c.1868, from the Gettysburg College Special Collections)

announced the reading of PRESIDENT LINCOLN’S inimitable address, by MAJOR HARRY T. LEE, a member of the Association.” [Henry (aka Harry) T. Lee, below left, from Kirk, Hyland C., Heavy Guns and Light: A History of the 4th NY Heavy Artillery (1890); and in a much later photo when he was a lawyer in Los Angeles, appearing in History of the Bench and Bar of Southern California (1909):[16]

Major Henry Thomas Lee was then a Professor in the Pardee Scientific Course of Lafayette College. He had “participated in the three days’ battle, serving on the staff of GEN. DOUBLEDAY” as a member of the 4th New York Artillery. He knows what happened here during the battle.

Major Henry Thomas Lee was then a Professor in the Pardee Scientific Course of Lafayette College. He had “participated in the three days’ battle, serving on the staff of GEN. DOUBLEDAY” as a member of the 4th New York Artillery. He knows what happened here during the battle.

Professor Stoever further explains that Major Lee “was also present at the consecration of the battle-ground, when the PRESIDENT’S speech was delivered”[17] at the time your 45th Pennsylvania was in the midst of its Knoxville campaign. You realize that the Major also knows what happened here at the cemetery dedication on November 19, 1863. On that topic, Major Lee made the following remarks:

“In the presence of these graves, within sight of Gettysburg, upon this doubly consecrated spot, it is fitting that no word should be uttered save that which comes from the heart; and its has been thought appropriate that in this solemn presence we should let our martyred PRESIDENT speak again as once before he spoke to an assembled multitude upon this crowded hillside, many of them the friends and relatives of those who sleep around us … [Major Lee then summarized the November 19, 1863 ceremonies:] REV. DR. STOCKTON opened the exercises with an impressive prayer which was followed by the Oration of HON. EDWARD EVERETT. The latter … although it was scholarly, masterly, exquisite; yet it failed to touch the heart. It was faultless as a Greek statue and — as cold. “

Maj. Lee paused for several seconds to let his last point sink in before proceeding:

“Then Lincoln arose, his face seamed and furrowed with marks of care, his eyes moist with tears, and in a voice tremulous with the deepest emotion, he pronounced in his simple and unaffected manner, The Speech of that memorable day. There was not a dry eye in the vast assemblage, and from the loud sobs that interrupted the PRESIDENT during some parts of his address, it was at times impossible to hear what he had to say.”

Contemporary accounts by several journalists reported how Lincoln let loose with several tears that day on the speakers’ platform during Rev. Stockton’s opening prayer. He moistened up yet again much later at a point of time in Edward Everett’s keynote oration when — “the sufferings of dying soldiers were recited [by Everett, and] scarcely a dry eye was visible, the President mingling his tears with those of the people.” Boston Journal, November 23, 1863. A similar account appeared in the Boston Advertiser, November 23, 1863.

You don’t fully understand the impact of Lincoln’s words described by the introductory remarks of Major Lee until the Major reads aloud Lincoln’s Dedicatory Address standing near where Lincoln had once stood on a platform. Lee orates it in a “clear and distinct voice … breaking the stillness of the solemn hour as though he stood alone upon the base of the [Soldiers’] monument.” What he recites aloud to you and your fellow teachers stirs your deepest emotions.

At the conclusion of the event, before returning to the Church in town, you reflect upon:

“the appropriate character of these exercises, the witching beauty of the twilight hour, the passing loveliness of the landscape …, tender thoughts of thirty-five hundred gallants sons of the Republic, martyrs of liberty, who sleep side by side in quiet graves; and the thousand thronging memories that came crowding upon the brain as [you] stood upon the great sacrificial Altar of Freedom.”

Moved, you find yourself asking rhetorically, “what member of the Association [here] present can ever forget this reading of the DEDICATORY ADDRESS on CEMETERY HILL?”

And later, back in your quarters, you record your closing thoughts on paper:

“Of the world’s great orators and authors not one in a hundred has really added anything permanent. But … in [his] address, LINCOLN has done for the American schoolboy what even WASHINGTON never did — has given him a “new speech” — which will do more through her growing youth to mould the patriotic sentiment of coming generations of American people, than is ever possible for even the grand Farewell Address of the “Father of our Country” to accomplish. Among all of the classic models which have become a power in moulding the sentiment of the civilized world, we know of nothing better or more appropriate for the purpose indicated then the brief address of ABRAHAM LINCOLN … It has already passed into our recently published school speakers and will be as familiar to the school-boy of the future, as Webster’s Repy to Hayne, or his famous speech on Bunker Hill. PRESIDENT LINCOLN was in error when he remarked so beautifully, ‘The world will little note nor long remember what we say here.’ His brief address will live as long as Cemetery Hill endures, as long as the world shall tell the deeds that have made Gettysburg immortal in story. To the teacher who may chance to read these paragraphs, we would say: Encourage your pupils to commit this ADDRESS to memory — never to be forgotten. Let the noble sentiment which it breathes become their life-long patriotic creed.” [emphasis added]

As you depart Gettysburg by train on August 2, 1866, headed for the depot in Hanover Junction, you reflect on the sights of and stories told on the Gettysburg battlefield and compare them in your mind to your own wartime experiences. You think of your dead friends and comrades left behind in makeshift graves in southern states who deserve a final resting place and honors of burial in a setting like the Gettysburg Soldiers’ Cemetery. But you also reflect upon the realization that some of what you have experienced in your three full days at Gettysburg faintly echoes elements of the Gettysburg Cemetery Dedication events. You understand your good fortune; this is as close as anyone could possibly have come to time traveling back to Gettysburg on November 19, 1863. From henceforth, you resolve that your curriculum for all students shall include the memorization and recitation of Lincoln’s Dedicatory Address at Gettysburg.

And it is your hope that enduring peace, prosperity, and a new birth of freedom shall be experienced by the next generation.

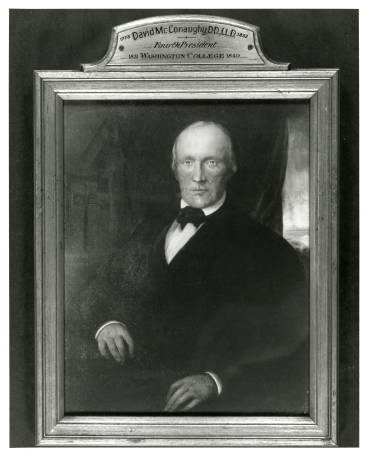

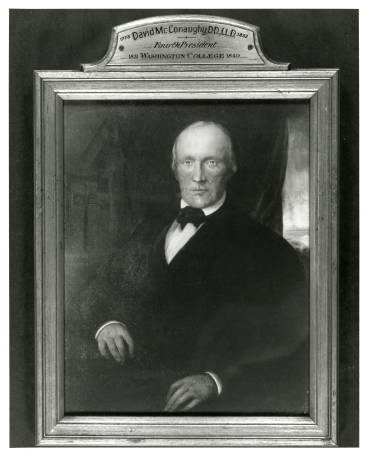

[Note: in reality, the Gettysburg Session of the Pennsylvania State Teachers’ Association did not conclude until the evening of August 2, 1866. On that morning, David McConaughy, a local State Senator, was introduced to the State Teachers’ Association in order to discuss the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association. Explaining that “the grandest monument of the battle is the field itself,” McConaughy stated that within 10 days after the battle’s end, Little Round Top (aka Granite Spur) was purchased so “that part of the field, in every respect possible, presents precisely the same appearance that it did at the close of battle.” He noted that other portions of the battlefield also had been bought by the Memorial Association and it was the group’s goal to buy all

“points of greatest interest ..; open a broad avenue along the main lines of battle; to erect an observatory upon Round Top; and also to erect everywhere low monuments and enduring structures of granite … [with] inscriptions upon these stones [which] tell the visitor … what happened here or there … and thus the Field of Gettysburg may become the Mecca of the American patriot, the perpetual teacher of a nation of freemen.”

Space does not allow for a description of McConaughy’s involvement in the creation of the Gettysburg Soldiers’ National Cemetery, his rivalry with David Wills, his oversight of the Evergreen Cemetery, and his ten year leadership of the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association, etc.]

One thing which really struck me when I first read the 1866 Pennsylvania School Journal article was its glowing praise of what we now call the “Gettysburg Address,” the statement that “it has already passed into our recently published school speakers,” and its earnest prodding that teachers should make their students memorize it. There are many historians who believe that the Gettysburg Address wasn’t widely embraced until much later when the cult of Lincoln had firmly taken root. This article suggests that many Pennsylvania teachers began emphasizing it in their classrooms relatively shortly after it was delivered — which might have occurred elsewhere too (e.g., this article was republished in the Oct. 1866 Rhode Island Schoolmaster journal). Having attended the moving 150th anniversary event at the Gettysburg National Cemetery in 2013, I have experienced the power of historical recreation. To have experienced Gettysburg in such a way in 1866 must have been quite an experience for anyone the least bit interested in American history. With all due respect to the undeniable talents of the recently deceased and beloved James A. Getty (may he rest in peace), the sincerity of Lincoln’s words narrated in the cemetery by a soldier/schoolteacher who had less than 3 years earlier witnessed Lincoln speak must have been even more powerfully conveyed and felt in 1866 than is possible today.

As for John Burns serving as one of the guides during the State Teachers’ Association visit, it wasn’t the only time he did such a thing. “Without realizing it, perhaps, the battle’s ‘civilian hero’ helped inaugurate a unique, distinctly individualistic, and somewhat lucrative occupation for some Gettysburg citizens” — serving as a battlefield guide. Bloom, Robert L., “‘We Never Expected a Battle’: The Civilians at Gettysburg, 1863,” Pennsylvania History, Vol. 55, No. 4 (October 1988) at p. 190.

Epilogue

Major Henry T. Lee’s 1866 description of Lincoln’s consecration address compares favorably with an even more contemporary account by another educator. Isaac Jackson Allen, a Whig, was the former president of Farmer’s College near Cincinnati and superintendent of that city’s school system before the war began. [I.J. Allen pictured below in 1901, aged 87, from Shotwell, John B., A History of the Schools of Cincinnati (1902)]:

For a portion of the war, Isaac Jackson Allen was the editor of the Daily Ohio State Journal of Columbus, OH. He was in Gettysburg as a journalist on November 19, 1863 because:

“Governor David Tod, of Ohio, invited me to join him as a member of his Staff, pro tempore; to this I assented, as that would give me the privilege of a seat on the platform at Gettysburgh. When there, I was seated near Mr. Lincoln, with whom were seated members of his Cabinet.”[18]

Isaac Jackson Allen reported the following in the November 23, 1863 edition of the Daily Ohio State Journal [emphasis added]:

“President Lincoln rose to deliver the Dedicatory Address. Instantly every eye was fixed and every voice hushed in expectant and respectful attention … The President’s calm but earnest utterance of this brief and beautiful address stirred the deepest fountains of feeling and emotion in the hearts of the vast throng before him; and, when he had concluded, scarcely could an untearful eye be seen, while sobs of smothered emotion were heard on every hand. At our side stood a stout stalwart officer, bearing the insignia of a captain’s rank, the empty sleeve of his coat indicating that he had stood where death was revelling [sic], and as the President, speaking of our Gettysburg soldiers, uttered that beautifully touching sentence, so sublime and pregnant of meaning —

‘The world will little note, nor long remember what we here SAY, but it can never forget what they here DID:’ [sic] —

The gallant soldier’s feelings burst over all restraint; and burrying [sic] his face in his manly frame shook with no unmanly emotion. In a few moments, with a stern struggle to master his emotions, he lifted his still streaming eyes to heaven and in low and solemn tones exclaimed, “God Almighty bless Abraham Lincoln!” And to this spontaneous invocation a thousand hearts around him silently responded, Amen!

In 1904, Allen further elaborated upon Lincoln’s performance:

“Then President Lincoln rose to deliver the Address of Dedication; advanced to the reading desk, put on his steel-rimmed spectacles, took from his vest pocket a thin slip of paper, laid it before him, glanced at it a moment; then, as if not able to see its writing very well, he crumpled it in his hand, returned it to his vest pocket, removed his spectacles, and proceeded to deliver that ever-memorable Dedicatory Address that has become a classic in our American literature, and which of itself would render the name of Abraham Lincoln immortal! He spoke but seven minutes. But, before he had spoken five minutes that whole assembled multitude were sobbing, and sympathetic tears were dimming all eyes. Lincoln’s simple eloquence of heart in speaking of our heroic dead had touched the responsive cords [of] feeling, that Everett’s finished oratory had failed to reach.”[19]

By Craig Heberton, October 3, 2015

————————————————————————————————————

[1] This account is based upon and quotes from “Thirteenth Annual Session of the Pennsylvania State Teachers’ Association,” Pennsylvania School Journal, September 1866, vol.15, No. 3, pp. 58-60. It imagines that you are one of the attendees at the session meeting and you have written at least the quoted sections from the above-cited article. I have taken the liberty of describing you as a veteran of the 45th Pennsylvania Regiment who after the war has returned to your job somewhere in Pennsylvania as a schoolteacher. All of the quoted language in this article relating to the Thirteenth Annual Session of the Pennsylvania State Teachers’ Association held in Gettysburg on July 31 and August 2, 1866 is from the published piece in the Pennsylvania School Journal, Vol.15, No. 3 (September 1866) first noted below in footnote 6 unless otherwise indicated.

[2] “You” are a fictitious character throughout this piece whom I have created in the attempt to place the reader into the shoes of a schoolteacher attendee at the Pennsylvania State Teachers’ Association Session in Gettysburg on July 31 and August 1, 1866. You are there primarily to see the battlefield and understand all of the hoopla over its fame. While there, you meet and speak to Rev. Henry L. Baugher, President of the Lutheran Theological Seminary in Gettysburg who gave the closing benediction on the speakers’ stand seconds after Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address;” John L. Burns (the “Hero of Gettysburg”) who likewise was present at the dedication event and walked arm-in-arm with President Lincoln to Gettysburg’s Presbyterian Church after the dedication ceremonies and a public reception at David Wills’ home; Colonel George Fisher McFarland, who was wounded at Gettysburg on July 1 while covering the First Corps’ retreat and had one of his legs amputated in the halls of the Lutheran Theological Seminary; and Major Henry T. Lee who both served at the Battle of Gettysburg under Doubleday and attended the Gettysburg Soldiers’ Cemetery Dedication event on November 19, 1863. Burns, McFarland, and Lee, among others, serve as your guides, taking you to some of the most dramatic portions of the battlefield and they describe to you what they saw and experienced. On Cemetery Hill, standing in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, Maj. Lee paints a picture of Lincoln’s address and then reads it in the way he recalls that Lincoln did less than 3 years earlier. Some of what you experience faintly echoes elements of the Gettysburg Cemetery Dedication event. It is a close as you will ever come to having been in Gettysburg on November 19, 1863.

[3] Perhaps there really was a member of the 45th Pennsylvania Regiment who survived the war, took a job as a teacher, and attended the Gettysburg Session of the Pennsylvania State Teachers’ Association held on July 31 to August 1, 1866. However, I’m not aware of such a person. If you do know of someone, by all means, let me know!

[4] Burrows, Thomas H., ed., “Thirteenth Annual Session of the Pennsylvania State Teachers’ Association,” Pennsylvania School Journal, Vol.15, No. 3 (September 1866) at p. 51.

[5] History of Cumberland County and Adams Counties, Pennsylvania (Beers & Co., 1886) at p. 372.

[6] Pennsylvania School Journal, Vol.15, No. 3 (September 1866) at pp. 51-52; Shelley was an advocate of the use of paying teacher incentives to reward quality teaching. See Wickersham, J.P., A History of Education in Pennsylvania, Private and Public Schools (1868) at pp. 8-9.

[7] Cincinnati Daily Commercial, November 24, 1863.

[8] Baugher’s benediction read: “O Thou King of kings and Lord of lords, God of the nations of the earth, who by Thy kind providence has permitted us to engage in these solemn services, grant us Thy blessing. Bless this consecrated ground, and these holy graves. Bless the President of these United States, and his Cabinet. Bless the Governors and the representatives of the States here assembled with all needed grace to conduct the affairs committed into their hands, to the glory of Thy name, and the greatest good of the people. May this great nation be delivered from treason and rebellion at home, and from the power of enemies abroad. And now may the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God our Heavenly Father, and the fellowship of the Holy Ghost, be with you all. Amen.”

[9] Not only had McFarland lost his leg, but his other wounded leg caused him great pain. It is presumed that he was transported about by horse-drawn carriage.

[10] http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=15909351; http://berks.pa-roots.com/Biographies/GeorgeFMcFarland.html

[11] Eventually, the wound received in his unamputated leg caused an infection which killed him in 1891. For more on the 151st Pennsylvania, see http://www.civilwar.org/education/teachers/teachers-regiment/trading-rulers-for-rifles.html.

[12] “Colonel McFarland’s Diary Reveals War-School Career,” Gettysburg Times, June 27, 1941; Deese, Michael A., The 151st Pennsylvania Volunteers at Gettysburg: Like Ripe Apples in a Storm at p. 6. For ideas related to teaching about McFarland, see http://www.gettysburglessons.com/blog/george-mcfarland-narrow-your-focus.

[13] McFarland, George F., “The Victory at Gettysburg, the Work of the Teacher,” The Pennsylvania School Journal (October 1866) at pp. 95-96.

[14] https://www.facebook.com/pages/151st-Pennsylvania-Volunteers-Company-D/138961739475266?sk=wall (July 23, 2014 entry on Capt. Owens).

[15] Captain Owens took command of the 151st Pennsylvania after Lt. Colonel McFarland was wounded and later captured. He maintained that command throughout the remaining days of the battle. “Colonel McFarland’s Diary Reveals War-School Career,” Gettysburg Times, June 27, 1941. The 151st was involved in repulsing “Pickett’s Charge” on the final day of battle and surely Captain Owen spoke about what he experienced near the Bloody Angle.

[16] http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=103257557

[17] Major Lee must have been present in Gettysburg on November 19, 1863 in his capacity as an aide on the staff of the then wounded Gen. Abner Doubleday. Doubleday was one of several wounded generals at Gettysburg who attended the dedication event. Lee “was never wounded” during the war, “but at Sutherland’s Station he received seven bullet-holes through his clothing.”

[18] Allen, Isaac Jackson. Memoranda Genealogical and Biographical Of the Allen Family (1904) at p. 25.

[19] http://www.jacksonfamilygenealogy.com/pages/bioIsaacJacksonAllenmemorandum.htm

Tags: 151st Pennsylvania, Aaron Shelley, Abner Doubleday, Abraham Lincoln, David McConaughy, Edward Everett, George F. McFarland, George Fisher McFarland, Gettysburg, Gettysburg Address, Gettysburg battlefield, Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association, Gettysburg National Cemetery, Henry L. Baugher, Henry T. Lee, Isaac Jackson Allen, John Burns, John F. Reynolds, Martin L. Stoever, Pennsylvania State Teachers' Association, Schoolteachers Regiment, Soldiers' National Cemetery, teach thyself, Teacher, Walter L. Owens

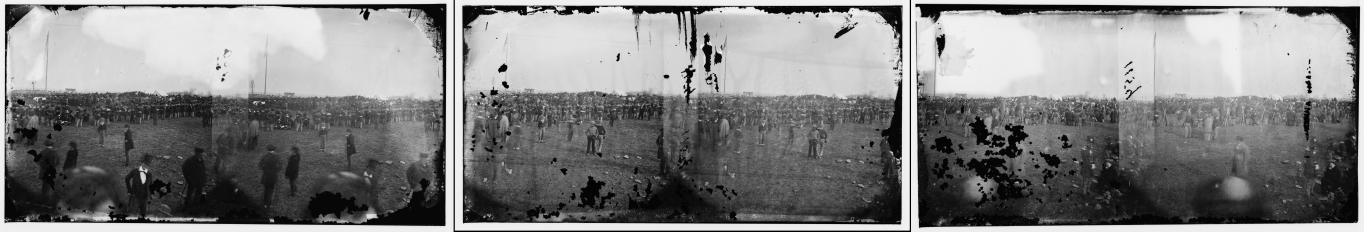

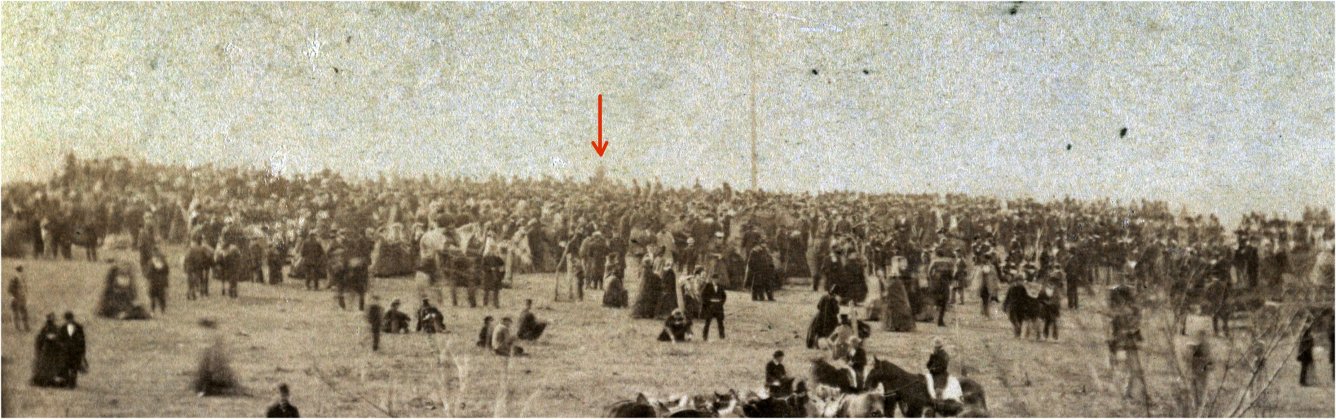

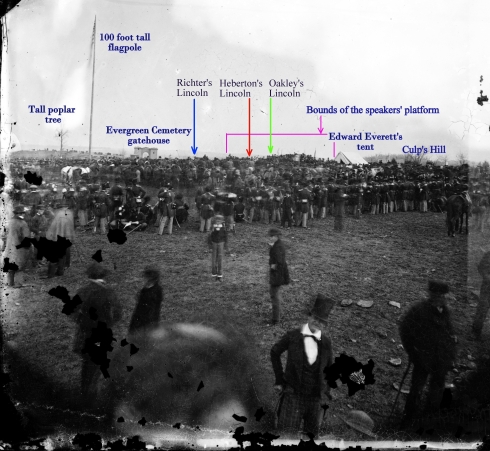

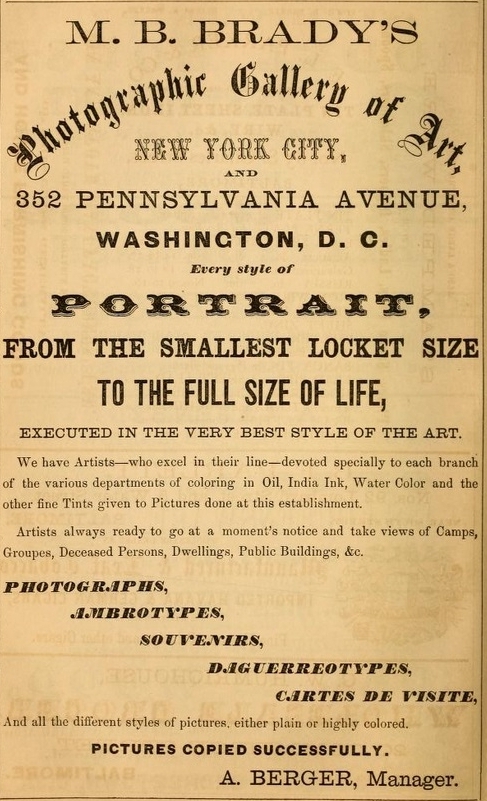

The Gardner photographers perched their dual lens camera atop some sort of a photographic platform which may have been nothing more sophisticated than a folding twelve foot ladder or two. Note the back of a partially bald head which appears in the lower portion of the immediate foreground in the first and last view above. It might be Alexander Gardner’s head captured as he faced out towards the historic scene while standing just below the camera on the front steps of a ladder. A later view of Gardner taken after the war near Manhattan, Kansas (according to R. Mark Katz) appears to reveal that he had that kind of male pattern balding.

The Gardner photographers perched their dual lens camera atop some sort of a photographic platform which may have been nothing more sophisticated than a folding twelve foot ladder or two. Note the back of a partially bald head which appears in the lower portion of the immediate foreground in the first and last view above. It might be Alexander Gardner’s head captured as he faced out towards the historic scene while standing just below the camera on the front steps of a ladder. A later view of Gardner taken after the war near Manhattan, Kansas (according to R. Mark Katz) appears to reveal that he had that kind of male pattern balding. Zooming in reveals a darker object beneath the man and just above the heads of several men either on horseback or standing on the front steps of the ladder(s) — likely Gardner’s camera (below).

Zooming in reveals a darker object beneath the man and just above the heads of several men either on horseback or standing on the front steps of the ladder(s) — likely Gardner’s camera (below).  That photographic platform was used in order to “see” over the large crowd and get a glimpse at portions of (and the area around) the speakers’ platform, as well as other key and unique features, such as a 100 foot tall flagpole erected for the occasion, the Evergreen Cemetery gatehouse, some of East Cemetery Hill, and a large white tent constructed for the privacy of Edward Everett, the keynote speaker. The left side of the first glass plate negative — LC-B815-1160 — exposed within the sequence of three is shown below (courtesy of the Library of Congress).

That photographic platform was used in order to “see” over the large crowd and get a glimpse at portions of (and the area around) the speakers’ platform, as well as other key and unique features, such as a 100 foot tall flagpole erected for the occasion, the Evergreen Cemetery gatehouse, some of East Cemetery Hill, and a large white tent constructed for the privacy of Edward Everett, the keynote speaker. The left side of the first glass plate negative — LC-B815-1160 — exposed within the sequence of three is shown below (courtesy of the Library of Congress).  The speakers’ platform, which was described by one observer as only 3 feet above the ground, faced not towards the Gardner photographic position, but was oriented from its center towards the tall flagpole. As described in this author’s book Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg (follow the link), the seating on the speaker’s rostrum was arranged in an orchestral fashion, with its several levels arcing around the center area of the first row where Lincoln sat. If you wonder why Gardner’s team set up their camera so far from the speakers’ platform, please read “Heberton’s Lincoln: The Case,” for an analysis. That article, in conjunction with the book Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg, also explains why Gardner likely chose to set up his photographic platform at such a severe angle to the speakers’ platform rather than selecting a more “head-on” perspective centered to the middle of the rostrum.

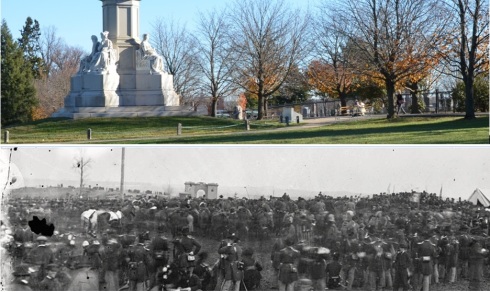

The speakers’ platform, which was described by one observer as only 3 feet above the ground, faced not towards the Gardner photographic position, but was oriented from its center towards the tall flagpole. As described in this author’s book Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg (follow the link), the seating on the speaker’s rostrum was arranged in an orchestral fashion, with its several levels arcing around the center area of the first row where Lincoln sat. If you wonder why Gardner’s team set up their camera so far from the speakers’ platform, please read “Heberton’s Lincoln: The Case,” for an analysis. That article, in conjunction with the book Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg, also explains why Gardner likely chose to set up his photographic platform at such a severe angle to the speakers’ platform rather than selecting a more “head-on” perspective centered to the middle of the rostrum. The Evergreen Cemetery gatehouse, clearly visible in the Gardner view, is almost completely obscured by trees in the modern view. Excluding an addition built after 1863, the gatehouse structure looks much today as it did then. The Gettysburg Soldiers’ National Monument currently stands where the tall flagpole (cropped at its top) is visible in the Gardner stereo view detail.

The Evergreen Cemetery gatehouse, clearly visible in the Gardner view, is almost completely obscured by trees in the modern view. Excluding an addition built after 1863, the gatehouse structure looks much today as it did then. The Gettysburg Soldiers’ National Monument currently stands where the tall flagpole (cropped at its top) is visible in the Gardner stereo view detail.

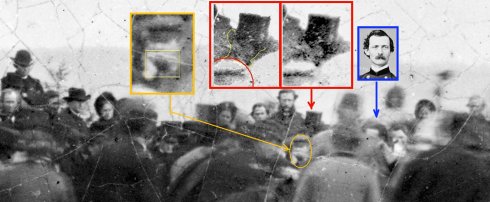

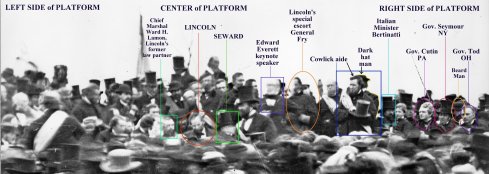

In early 2008, William A. Frassanito posted an article at a friend’s blog (follow the link) which opined that the man Mr. Richter identified as Lincoln wasn’t Honest Abe and added several arguments why it was virtually impossible for Lincoln to have been visible when any of the stereo views were taken. Mr. Frassanito wrote that “it is well documented that Lincoln was accompanied and flanked by several mounted civilians, including the chief marshal and three members of Lincoln’s cabinet” and concluded that the three images reveal that all of Gardner’s views were taken only after Lincoln and the other dignitaries had been seated on the speakers’ platform.

In early 2008, William A. Frassanito posted an article at a friend’s blog (follow the link) which opined that the man Mr. Richter identified as Lincoln wasn’t Honest Abe and added several arguments why it was virtually impossible for Lincoln to have been visible when any of the stereo views were taken. Mr. Frassanito wrote that “it is well documented that Lincoln was accompanied and flanked by several mounted civilians, including the chief marshal and three members of Lincoln’s cabinet” and concluded that the three images reveal that all of Gardner’s views were taken only after Lincoln and the other dignitaries had been seated on the speakers’ platform.

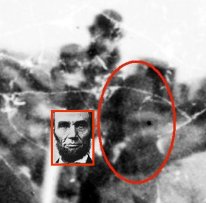

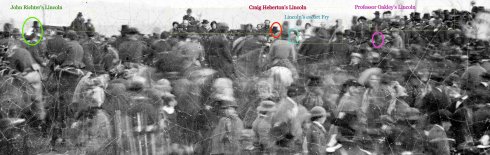

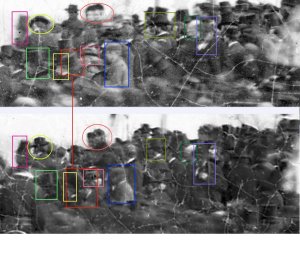

Because this man’s face appears in dark shadows created by the brow of his hat in the first view and he likely moved during much of the lengthy exposure in the second view creating a “ghost image” in front of a “fixed” image of his tall silk hat, the case for this candidate as Lincoln is more heavily anchored to substantial contextual support. See detail, below, from the first-in-time Gardner stereo view revealing the relative positions of Mr. Richter’s candidate, this author’s candidate, and Mr. Oakley’s candidate (discussed below).

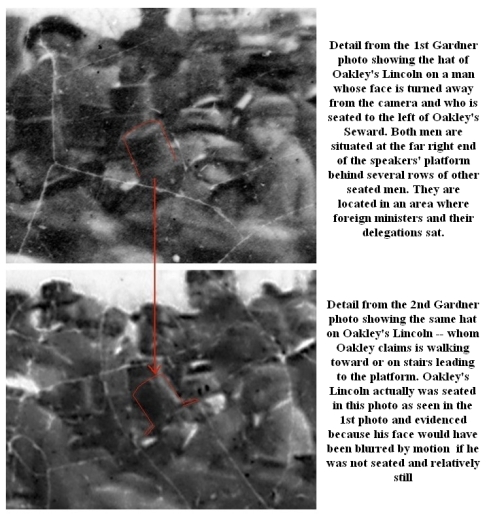

Because this man’s face appears in dark shadows created by the brow of his hat in the first view and he likely moved during much of the lengthy exposure in the second view creating a “ghost image” in front of a “fixed” image of his tall silk hat, the case for this candidate as Lincoln is more heavily anchored to substantial contextual support. See detail, below, from the first-in-time Gardner stereo view revealing the relative positions of Mr. Richter’s candidate, this author’s candidate, and Mr. Oakley’s candidate (discussed below).  But there is a third candidate. The Smithsonian Magazine, in its October 2013 article “Will the Real Abraham Lincoln Please Stand Up?,” proclaimed that within one of the Alex Gardner stereo views, Christopher Oakley had made “what looks to be the most significant, if not the most provocative, Abraham Lincoln photo find of the last 60 years.” Mr. Oakley asserted that his candidate was “accidentally” captured by Gardner’s camera as he stood frozen throughout the entire passage of that plate’s lengthy exposure while stooped over, looking at the ground beneath him, and holding a rigid pose for several seconds despite surmounting unseen steps leading to the platform. The many reasons why Professor Oakley’s candidate cannot be Abraham Lincoln — ranging from his completely mismatched nose to the fact that he is seated (not standing) in two photos nowhere near the spot that Lincoln is documented to have been seated, “guarded” by two little boys, and ignored by all of the visible spectators on the speakers’ platform — are laid out in “Heberton’s Lincoln: The Case,” “Where is Lincoln?: Heberton Takes on the Flaws in Oakley’s Case,” the press release “Should Oakley’s Lincoln Sit Down?,” and “The Big Picture: Where Would Lincoln Be? Heberton Reveals His Findings.” Click on those links also for a fuller explanation of the case for this author’s Lincoln candidate. Here is Mr. Oakley’s “enhanced” representation of his hawk-nosed Lincoln candidate which he presented on the CBS Evening News broadcast on November 19, 2013 along with detail from Gardner’s second stereo view at the Library of Congress.

But there is a third candidate. The Smithsonian Magazine, in its October 2013 article “Will the Real Abraham Lincoln Please Stand Up?,” proclaimed that within one of the Alex Gardner stereo views, Christopher Oakley had made “what looks to be the most significant, if not the most provocative, Abraham Lincoln photo find of the last 60 years.” Mr. Oakley asserted that his candidate was “accidentally” captured by Gardner’s camera as he stood frozen throughout the entire passage of that plate’s lengthy exposure while stooped over, looking at the ground beneath him, and holding a rigid pose for several seconds despite surmounting unseen steps leading to the platform. The many reasons why Professor Oakley’s candidate cannot be Abraham Lincoln — ranging from his completely mismatched nose to the fact that he is seated (not standing) in two photos nowhere near the spot that Lincoln is documented to have been seated, “guarded” by two little boys, and ignored by all of the visible spectators on the speakers’ platform — are laid out in “Heberton’s Lincoln: The Case,” “Where is Lincoln?: Heberton Takes on the Flaws in Oakley’s Case,” the press release “Should Oakley’s Lincoln Sit Down?,” and “The Big Picture: Where Would Lincoln Be? Heberton Reveals His Findings.” Click on those links also for a fuller explanation of the case for this author’s Lincoln candidate. Here is Mr. Oakley’s “enhanced” representation of his hawk-nosed Lincoln candidate which he presented on the CBS Evening News broadcast on November 19, 2013 along with detail from Gardner’s second stereo view at the Library of Congress.

A visual review of the detail within the first and second Gardner view reveals that Mr. Oakley’s candidate was seated in the same spot in both views. That location is at the extreme far end of the platform and, as can been seen, is not in the first row of seats. Moreover, Mr. Oakley claims that the man seated to the right of his candidate for Lincoln is Secretary of State William H. Seward. Lincoln, in actuality, was seated in the center of the front row, with Seward to his left, nowhere near Mr. Oakley’s candidate pictured below:

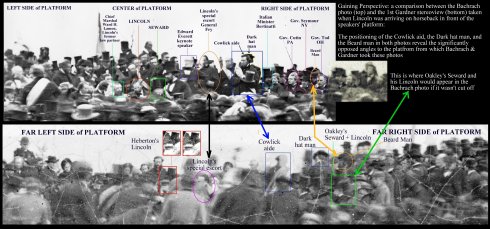

A visual review of the detail within the first and second Gardner view reveals that Mr. Oakley’s candidate was seated in the same spot in both views. That location is at the extreme far end of the platform and, as can been seen, is not in the first row of seats. Moreover, Mr. Oakley claims that the man seated to the right of his candidate for Lincoln is Secretary of State William H. Seward. Lincoln, in actuality, was seated in the center of the front row, with Seward to his left, nowhere near Mr. Oakley’s candidate pictured below: Below is a comparison between a different photograph (on the top) attributed to photographer David Bachrach showing exactly where Lincoln was seated with Seward to his left (rather than to his right) and the Gardner stereo (on the bottom). The Bachrach photo is marked to illustrate the area where Mr. Oakley’s candidate was seated had it been visible in that view. This gives one a perspective of how far removed Mr. Oakley’s candidate was situated from where President Lincoln sat.

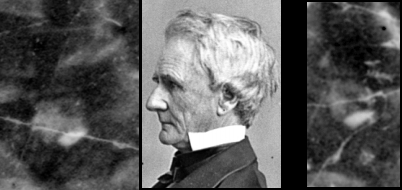

Below is a comparison between a different photograph (on the top) attributed to photographer David Bachrach showing exactly where Lincoln was seated with Seward to his left (rather than to his right) and the Gardner stereo (on the bottom). The Bachrach photo is marked to illustrate the area where Mr. Oakley’s candidate was seated had it been visible in that view. This gives one a perspective of how far removed Mr. Oakley’s candidate was situated from where President Lincoln sat. Presently, this author believes that Mr. Oakley’s candidate for Seward could be soft-chinned Simon Cameron, who earlier in 1863 had resigned his position as the U.S. minister to Russia and returned to his native Pennsylvania. Before his appointment as ambassador, Cameron had stepped down as Lincoln’s Secretary of War in January of 1862 because of “mismanagement, corruption and abuse of patronage.” This would explain why he was seated in an area relatively proximate to where a number of foreign diplomats were situated but well removed from Lincoln. See, below, a horizontally flipped studio image of Simon Cameron (courtesy, the Library of Congress) placed in the middle of cropped detail of the man whom Mr. Oakley has unequivocally identified as Seward.

Presently, this author believes that Mr. Oakley’s candidate for Seward could be soft-chinned Simon Cameron, who earlier in 1863 had resigned his position as the U.S. minister to Russia and returned to his native Pennsylvania. Before his appointment as ambassador, Cameron had stepped down as Lincoln’s Secretary of War in January of 1862 because of “mismanagement, corruption and abuse of patronage.” This would explain why he was seated in an area relatively proximate to where a number of foreign diplomats were situated but well removed from Lincoln. See, below, a horizontally flipped studio image of Simon Cameron (courtesy, the Library of Congress) placed in the middle of cropped detail of the man whom Mr. Oakley has unequivocally identified as Seward. The left side of the first exposed Gardner negative at Gettysburg — LC-B815-1160 — is marked, below, to show the locations of the three Lincoln candidates.

The left side of the first exposed Gardner negative at Gettysburg — LC-B815-1160 — is marked, below, to show the locations of the three Lincoln candidates. What is to be made of these 3 Lincoln candidates? Some people embrace one of them as Lincoln. Some just don’t know or are bewildered when they too quickly attempt to interpret the photographic evidence and ignore the contextual documentary evidence. Others adhere to the position that Gardner merely took three “establishing” or “generic crowd shots” (representing the sum total of his photographic work at Gettysburg on November 19, 1863), had zero interest in capturing a scene with Lincoln, and didn’t even accidentally capture Lincoln in any of the three stereo views. Nevertheless, an evaluation of whether Gardner intentionally placed his camera where he did in order to try to capture two relatively rapid-fire views of Lincoln arriving at the Cemetery upon his horse + one much later view of the famous keynote speaker, Edward Everett, arriving on the speaker’s platform is laid out in Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg and several of this author’s blog articles at abrahamlincolnatgettysburg.wordpress.com.

What is to be made of these 3 Lincoln candidates? Some people embrace one of them as Lincoln. Some just don’t know or are bewildered when they too quickly attempt to interpret the photographic evidence and ignore the contextual documentary evidence. Others adhere to the position that Gardner merely took three “establishing” or “generic crowd shots” (representing the sum total of his photographic work at Gettysburg on November 19, 1863), had zero interest in capturing a scene with Lincoln, and didn’t even accidentally capture Lincoln in any of the three stereo views. Nevertheless, an evaluation of whether Gardner intentionally placed his camera where he did in order to try to capture two relatively rapid-fire views of Lincoln arriving at the Cemetery upon his horse + one much later view of the famous keynote speaker, Edward Everett, arriving on the speaker’s platform is laid out in Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg and several of this author’s blog articles at abrahamlincolnatgettysburg.wordpress.com.![3 Lincoln comparison 2015-11-16[2]](https://abrahamlincolnatgettysburg.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/3-lincoln-comparison-2015-11-162.jpg?w=634&h=453)

Recent Comments