WHERE ARE THE CANDIDATES FOR LINCOLN?

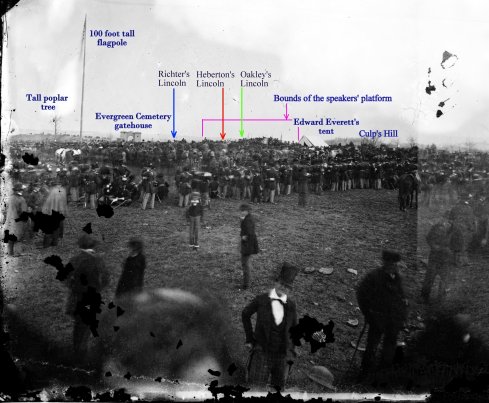

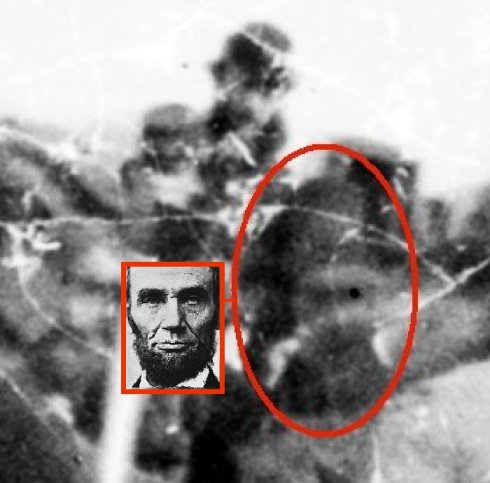

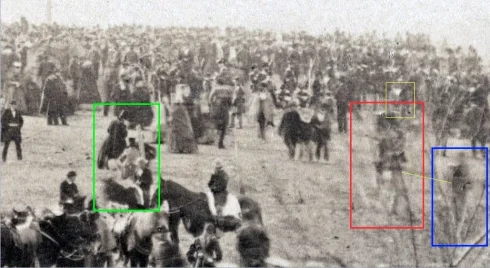

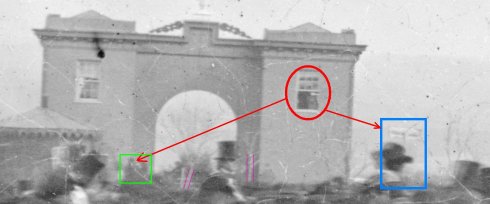

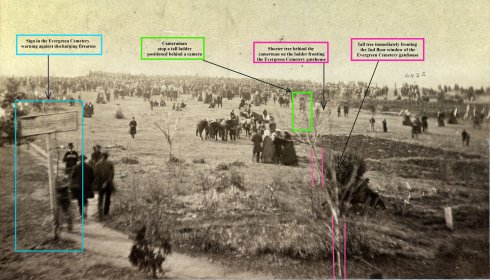

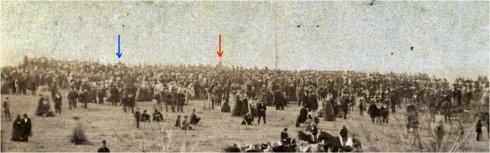

To provide the necessary perspective, take a look at what the Library of Congress (LC) refers to as the stereo view from the left side of the negative for the first-in-time Gardner photo (first sequenced by Craig Heberton). It is marked (below) to illustrate key landmarks as well as, from left to right, the locations of John J. Richter’s Lincoln, Craig Heberton’s Lincoln, and Christopher Oakley’s Lincoln. This illustrates how far Gardner felt compelled to set up his photographic platform or ladder from the hollow square of foot soldiers in order to be able to “see” over those infantrymen, the soldiers and aides on horseback, and the thousands of spectators standing on higher ground.

WHY WAS LINCOLN PHOTOGRAPHED AT A DISTANCE?

The fact that all known photographs depicting the Soldiers’ Cemetery and Evergreen Cemetery grounds on November 19, 1863 were taken outside the hollow square of soldiers illustrates two points. First, it would have been difficult for wet-plate photographers to set up their necessary equipment near a portable darkroom inside the hollow square because: (a) the darkroom had to be near the camera to allow for both the preparation and development of glass photographic plates within the darkroom near the time of their use, (b) the darkroom, the wet-plate chemicals, and the photographic platform couldn’t be placed where they would be in danger of being knocked over, trampled upon, or the plates otherwise might be ruined or diminished in quality, (c) to get inside the hollow square, the photographers might have had to march at the tail end of the parade and their equipment would have been transported by horseback in that no wagons can be seen anywhere within the hollow square, and (d) a wet-plate cameramen within the hollow square might have been compelled to place his equipment outside of the packed inner ring of spectators with a potentially worse view of the platform than outside of the hollow square. Second, even assuming that wet-plate photographers could have gained access to the area immediately in front of the speakers’ platform, it has to be asked whether they would have been comfortable placing a portable darkroom near their camera or forced to place it outside the inner ring of spectators at a great distance from and possibly inaccessible to the camera because of the crush of the crowds (described in several accounts)? It seems more likely, as speculated by John J. Richter, that only a dry-plate camera operator could have overcome the many obstacles within the hollow square thanks to the ease-of-use of those plates. In so doing, a dry-plate operator would have sacrificed image quality in exchange for convenience and maneuverability. Dry-plate technology “did not require sensitization and processing of plates while still wet in the field” and “the most important technical contribution by amateurs in [the 1860s] is the effort to develop a dry plate negative process …” John Hannavy, ed., Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, Volume I (2007), at p. 33. The diminished quality of early rudimentary dry-plate technology is the reason why it was used almost exclusively in the 1860s by wealthy men of leisure and/or very technically savvy amateurs. For all of these reasons and more, it can be understood why the wet-plate photographers present at the dedication ceremony in Gettysburg on November 19, 1863 may have been compelled to shoot all or nearly all of their plates atop some form of a photographic platform from the relative safety of the area outside the hollow square. John Richter’s thoughtful analysis about these considerations, in collaboration with Mr. Heberton, is very helpful in answering why Lincoln was photographed at such a distance.

GAINING PERSPECTIVE

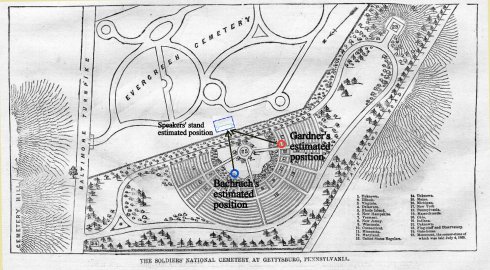

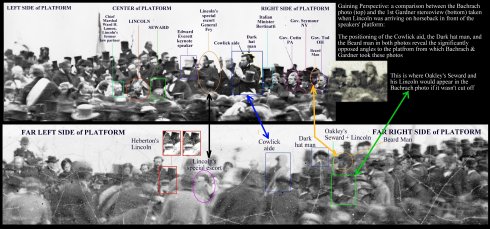

It is difficult at first blush to realize the extent to which the cameras of Gardner and Bachrach were positioned in relatively opposing angles to the speakers’ platform on the cemetery grounds. The marked map, below, allows one to acclimate to those differing views.

Although the first two Gardner stereoviews were exposed as Lincoln was arriving on horseback and taking part in a reception for him directly in front of the platform, several men observable in the later Bachrach photo (taken when Lincoln was seated and Edward Everett was standing and orating) can be seen upon the platform in the Gardner stereoviews. They were among the many already in position on the rostrum BEFORE Lincoln surmounted steps to join them. The positioning of those men allows for a determination of the different camera angles of each of Gardner and Bachrach and visually “explains” why Professor Oakley’s candidate cannot be correct.

The area in which Professor Oakley claims that Secretary of State Seward was seated for ten minutes before his candidate for Lincoln arrived to be seated next to him is so very far away from the correct spot in which both Seward and Lincoln actually were seated. The WRONG location is is just one of several reasons why his thesis is fatally flawed.

A SUMMARY OF WHY OAKLEY’s CANDIDATE FOR LINCOLN IS FLAWED

- His Lincoln commands no attention from anyone in the crowd — Lincoln was described as “the observed of all observers” when he arrived before the speakers’ platform; Oakley’s Lincoln is the most unobserved of the observed. Men seated and standing on the platform ignore him. No one in the crowd standing on the ground near him doffed their hats in a show of respect, as occurred repeatedly wherever Lincoln appeared in Gettysburg. A review of the Gardner photos shows that the visible crowd is collectively focused upon someone else — not only in the first Gardner stereo view but in the second Gardner photo too. That person, who was the “observed of all observers,” is located in an area nowhere near Oakley’s Seward and Lincoln. This alone undercuts his Lincoln identification.

- No dignitaries are on their feet preparing to greet his Lincoln as he allegedly prepares to surmount steps while stooped over as if he already is seated.

- His Lincoln is completely unaccompanied and no one can be seen trailing behind him over a distance of at least forty or fifty yards.

- William A. Frassanito argued against John Richter’s candidate in 2008 by pointing out that he was unaccompanied by cabinet members Seward, Blair, and Usher — the same argument can be applied against Oakley’s Lincoln whom Oakley says trailed his Seward to the cemetery by 10 minutes (nearly the same amount of time as some say it took Lincoln to ride from the town square to the outskirts of the cemetery). Likewise, Secretaries Usher and Blair are nowhere visible near him even though several accounts describe that Lincoln trailed Seward, Usher, and Blair up onto the rostrum.

- His alleged Secretary of State Seward was seated on the platform 10 minutes (or more) before his Lincoln is said to be seen in the second (but not the first) Gardner photo standing and not yet seated.

- His alleged Secretary of State Seward is seated at the far right end of the platform, several rows behind other men situated with their backs to him nowhere near the spot where Seward is shown seated in the center of the front row of chairs on the speakers’ platform in the Bachrach photo. Accounts also place Seward where he is shown in the Bachrach photo.

- His alleged Seward is “guarded” by young boys standing behind him on the platform in both of the first two Gardner stereo views.

- Men in the crowd are not seen removing their hats in a show of respect for his alleged Lincoln.

- His Lincoln allegedly was moving throughout the exposure of the second Gardner stereo view as he walked up (or moved to the base of) stairs; if so, Gardner’s camera from a distance of about 90 yards away never would have captured the facial details claimed to match Lincoln’s studio photo taken from a distance of a few feet when Lincoln sat ramrod straight and perfectly still for Gardner’s several second indoor exposure. Oakley’s Lincoln must have been seated, otherwise his face would have been blurred, twinned, or appeared as a ghost image. Plenty of visual evidence of multiple ghost images of people who moved substantial distances throughout the camera’s exposure supports the conclusion that the second Gardner stereo view was exposed for as long as 10 to 12 seconds.

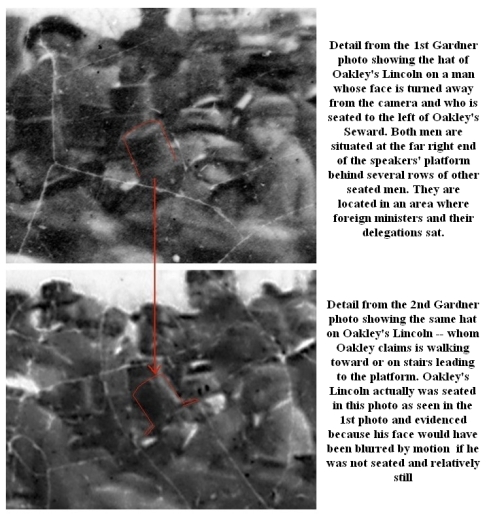

- Professor Oakley claims that his Lincoln was soon to be seated to the left of his alleged Seward in the second Gardner stereo view.

- His Lincoln, in truth, is visible in the first Gardner photo seated in the exact location as he is seen in the second photo — to the left of his alleged Seward (see below). His hat is visible in the first stereo angled in the same orientation as seen in the second Gardner stereo. His Lincoln’s face happened to be turned away from the camera in the first stereo view.

- His Lincoln is seated on the extreme far right of the platform behind several rows of standing and seated men when all accounts and the Bachrach photo place Lincoln and Seward in the exact center of the front row of seats on the stand — befitting their stature and importance. David Wills, Esq. and Governor Curtin never would have seated the President and Secretary of State anywhere near where Professor Oakley places them.

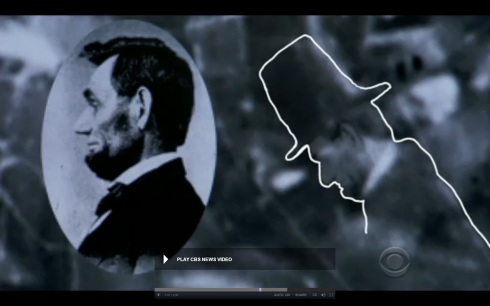

- The nose on his Lincoln is “hawk-shaped;” but Lincoln’s substantial nose was not hooked. In the Smithsonian article trumpeting Professor Oakley’s discovery, the one prominent facial feature which Professor Oakley does not list as matching Lincoln’s face is his nose. In a side profile view, one’s nose usually is their most prominent feature. With respect to Lincoln’s substantial nose, that is the case for sure. To my knowledge, not until an interview with the CBS Evening News on November 19, 2013 did Professor Oakley declare his Lincoln’s nose to be a “match” to Lincoln’s. This he did after first showing a highlighted image of his Lincoln’s face — hooked nose and all. He then showed a computer screen view of his Lincoln’s face already overlaid with a transparency of a scaled-down Alexander Gardner studio photo of Lincoln taken on November 8, 1863 and further framed by an outline of Lincoln’s face seen in that studio photo. A favorable response by CBS reporter Chip Reid was captured on air when, in fact, Reid viewed, in essence, nothing more than Lincoln’s studio photo taken on November 8, 1863 placed within Gardner’s second stereo view shot outdoors on November 19, 1863 which was overlaid on top of the Professor’s candidate for Lincoln. See the screen captures from the broadcast, below.

- The “beard” on his Lincoln’s chin is tucked into his shirt and many shades darker than the rest of his facial hair; Professor Oakley has conveniently carved out from the dark blob at the base of his Lincoln’s chin only a tiny portion of that which he claims matches Lincoln’s beard. In essence, he sees what he wants to see and has made it so.

- His Lincoln’s “beard” is just as likely a bow tie or the entire dark blob represents a beard far larger than Lincoln’s December 8, 1863 studio photo.

- Exclusive reliance upon an alleged visual identification of Seward and Lincoln, without a comprehensive comparative review of details within all three Gardner stereo photos (let alone the written historical record) is insufficient proof. Oakley’s Seward cannot be Seward merely because of where he is seated and when he is said to be seated. Likewise, his Lincoln cannot be Lincoln for the same reasons. No measure of photo software enhancement, overlays, rotation of studio photos, and other technological applications can change that.

The screen captures (above) from the CBS Evening News interview originally broadcasted on November 19, 2013 are used herein under the fair use doctrine and principles of fair dealing, as they are used for comment, scholarship, and research.

HEBERTON’s LINCOLN

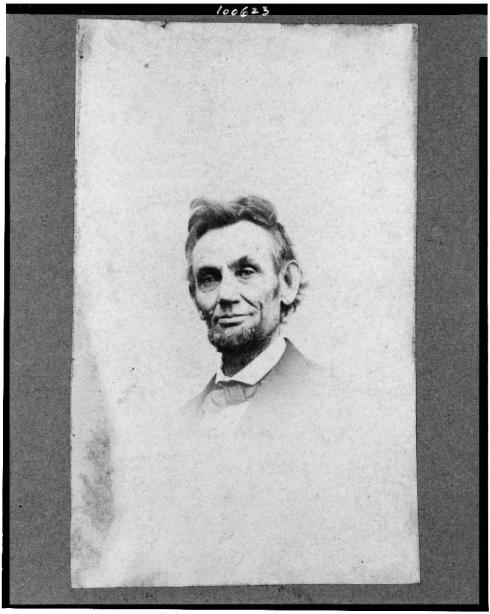

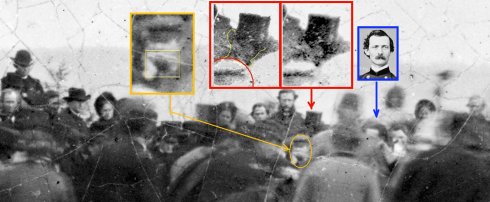

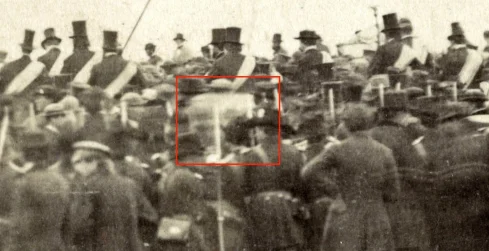

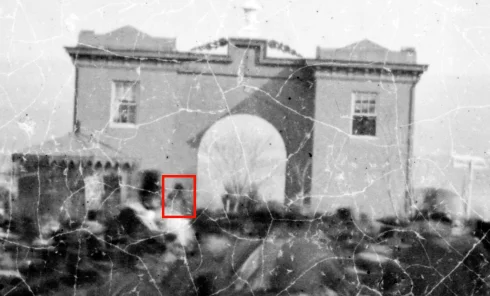

There are numerous accounts that Lincoln wore white gloves over his large hands and a stovepipe hat wrapped with a mourning band in Gettysburg. Detail from the first Gardner photo reveals the heavily shadowed face of a bearded man (see below, boxed in red) with a prominent motion-distorted nose and an equally large right ear beneath a stovepipe hat adorned by a mourning band. The elaborately intricate outer cartilage of his proportionately over-sized right ear can be seen along with a small, rounded jutting chin covered by a dark beard. In this Gardner photo he is the object of the most intense scrutiny of all visible men and women who are standing upon the speakers’ platform and facing Gardner’s camera (“Heberton’s Lincoln”) despite being turned away from them — just as President Lincoln would have been. In the words of one journalist, Lincoln was “the observed of all observers” when he appeared before the rostrum. Many accounts explain that this was so from the moment that Lincoln stepped off his train after arriving in Gettysburg on November 18, 1863 until he departed Gettysburg the following day after giving his “Address,” returning to the town square from the cemetery, dining, shaking hands with thousands of well-wishers at the Wills home, and visiting the town’s Presbyterian church for a final reception with local “hero” John Burns.

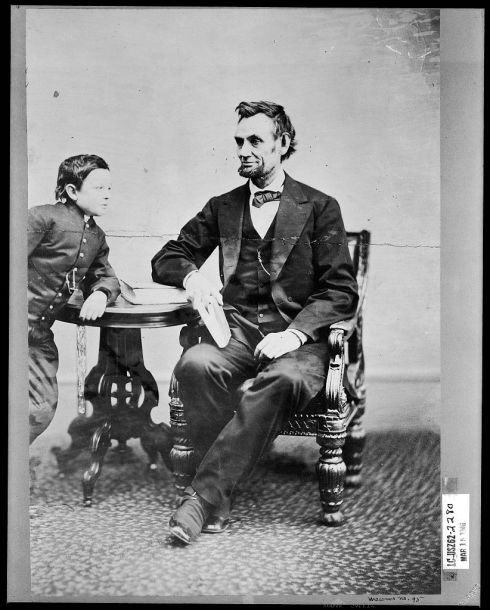

Many studio photographs reveal that Lincoln’s nose and ears were quite large in proportion to the rest of his long face and that his dark beard covered a portion of his prominently rounded and jutting chin, just as can be seen in the first Gardner stereo view. See, below, a photo of Lincoln from the LC taken during his presidency, illustrating his massively high forehead, lengthy neckline, long and prominent nose, over-sized ears, and rounded, jutting chin.

The forward-facing visible grandstand spectators in the scene captured by Gardner were standing on the highest tiers of the speakers’ platform, looking down over others standing beneath them and then ultimately over as many as three rows of chairs on the lowest level of the front of the rostrum set up in a bowed orchestral-like formation. They are seen staring at the singular object of their collective attention fronting the speakers’ platform. It is estimated that they were at a distance of at least 100 yards from Gardner’s camera location (the focal acuity of the dual lenses of Gardner’s camera at this distance was very good so long as objects remained still throughout its four to five second exposure and were not shaded from the sun — note: the second Gardner photo had an exposure time of at least 10-12 seconds). One hatless military man strains to peek at Heberton’s Lincoln by looking over the right shoulder of a taller, mutton-chopped Colonel Henry P. Martin who is standing in front of him also without a topper. Some other men are hatless too. Even the men with their backs to Gardner on horseback — who are situated between Gardner and the rostrum — are all oriented in the direction of Heberton’s Lincoln, appearing equally transfixed.

The forward-facing visible grandstand spectators in the scene captured by Gardner were standing on the highest tiers of the speakers’ platform, looking down over others standing beneath them and then ultimately over as many as three rows of chairs on the lowest level of the front of the rostrum set up in a bowed orchestral-like formation. They are seen staring at the singular object of their collective attention fronting the speakers’ platform. It is estimated that they were at a distance of at least 100 yards from Gardner’s camera location (the focal acuity of the dual lenses of Gardner’s camera at this distance was very good so long as objects remained still throughout its four to five second exposure and were not shaded from the sun — note: the second Gardner photo had an exposure time of at least 10-12 seconds). One hatless military man strains to peek at Heberton’s Lincoln by looking over the right shoulder of a taller, mutton-chopped Colonel Henry P. Martin who is standing in front of him also without a topper. Some other men are hatless too. Even the men with their backs to Gardner on horseback — who are situated between Gardner and the rostrum — are all oriented in the direction of Heberton’s Lincoln, appearing equally transfixed.

The only person in the scene not looking at Heberton’s Lincoln is the boy circled in yellow, above. Heberton’s Lincoln gazes down upon upon that boy benevolently with a leftward-tilted, cocked head. The angle at which Heberton’s Lincoln’s hat is oriented results in its motion-obscured brim blocking all of the November sun’s rays from his face. People who knew Lincoln described that he came to favor wearing unusually wide brimmed hats. The boy fronts Heberton’s Lincoln in the manner seen because he is seated in front of Heberton’s Lincoln, presumably on the same saddle of a hidden horse. A large white-gloved left hand from Heberton’s Lincoln — palm side up, with fingers extended — obscures the boy’s mouth and chin from Gardner’s camera. We may see a portion of the boy’s right hand grasping the right side of his face as if he cannot believe what is happening to him and/or looking at something before him in semi-amazement. Possibly standing before the boy at the moment was a portion of a detachment of the Invalid Corps extending an official greeting to their president. These men were wounded at the battle of Gettysburg and deemed unfit to be returned to combat duty but capable of performing other services. They may have been gathered to greet Lincoln near the eagle finial-topped staff (seen within the detail, above, to the far right) stationed to mark the beginning of the corridor of soldiers positioned in front of the rostrum. In the words of one eyewitness — “Easily the feature of the parade was a detachment of forty soldiers who had been injured in the battle and who had been removed to the military hospital at York, thirty miles to the east. They were sent to represent their comrades, every one bearing the marks of the fearful struggle, many of them on crutches. They carried a large white banner draped in mourning which bore this inscription on one side: ‘Army of the Potomac, Gettysburg, July 1, 2, 3, 1863.’ and on the other side appeared the likeness of a funeral urn and the tribute: ‘Honor to our brave soldiers.'” Why might Lincoln have scooped up a boy appearing to be around the age of 10 and placed him on his saddle in front of the speakers’ platform? The context of what was then happening provides a cogent answer: Lincoln’s 10 year-old son, Tad, was back at the White House fighting a potentially life-threatening case of smallpox. Mary Todd Lincoln had urged her husband not to go to Gettysburg in light of Tad’s serious condition (she also was recovering from being thrown from the Lincoln’s carriage and injuring her head in an accident she believed to have resulted from an act of sabotage). Lincoln received telegrams in Gettysburg from Stanton and his wife before riding in the procession which assured him that Tad was improving rather than taking a turn for the worse. Those messages must have taken some of the huge weight off of his shoulders. Many accounts describe how focused Lincoln was on touching, greeting, kissing, and shaking hands with the children he encountered in Gettysburg. For example, Rev. D.A. Dickson recounted that — “As the Presidential party in the procession was passing through the Public Square on its way to Baltimore Street, a man standing close to the line held high in his arms his little girl dressed in white. Lincoln reached out his long arms, lifted the child to a place on his horse before him, kissed her, then handed her back to her happy father.” Thus, we have at least one account of Lincoln bringing a child up onto his saddle — in this case, a stand-in for the daughter Lincoln never had. The boy seen on the saddle of Lincoln’s horse in the first Gardner stereo view may have served as a form of temporary surrogate for his beloved Tad. Had Tad not been ill, he might have accompanied his father and mother to Gettysburg and ridden on the saddle of his father’s horse. Several accounts confirm that students who were directed to walk at the back of the procession from the town center were brought forward once they reached the cemetery and passed through the massive crowds with Lincoln’s entourage to the very front of the speakers’ platform. The boy we see in Gardner’s stereo view may have been one of those children — the luckiest of them all. Below is a photo of Lincoln with Tad from the LC:

Trailing behind Heberton’s Lincoln, wearing white gauntlets on his hands, is Colonel James Barnet Fry, then the Provost Marshal General (boxed in blue in the first image, above). He is seated atop his horse closer to Gardner’s camera than Heberton’s Lincoln and may have been executing a left-handed salute with a riding crop in his left hand. Fry was Marshal-in-Chief Ward H. Lamon’s boss in Washington, D.C. — in Lamon’s capacity as the U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia — and had been designated by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to serve as Lincoln’s special escort in Gettysburg. Fry later wrote: “I was designated by the Secretary of War as a sort of special escort to accompany the President from Washington to Gettysburg upon the occasion of the first anniversary of the battle at that place. At the appointed time I found the President’s carriage at the door to take him to the station; but he was not ready. When he appeared it was rather late, and I remarked that he had no time to lose in going to the train. ‘Well,’ said he, ‘I feel about that as the convict in one of our Illinois towns felt when he was going to the gallows. As he passed along the road in the custody of the sheriff, the people, eager to see the execution, kept crowding and pushing past him. At last he called out, ‘Boys! you needn’t be in such a hurry to get ahead, for there won’t be any fun till I get there.'” The column in which Lincoln rode in the procession, consisting of Marshal-in-Chief Lamon (Lincoln’s former law partner and confidant), Secretary of State Seward, Secretary of the Interior John P. Usher, and Postmaster-General Montgomery Blair, was immediately trailed by Provost Marshal General Fry’s column. Personally attending to Lincoln’s safety was Fry’s highest duty in Gettysburg. Detail from each of the stereos of the second Gardner stereo view from the LC’s collection, taken an estimated minute after the first view, can be seen below. According to Bob Zeller, no other outdoor Civil War photographs framing the exact same space are known to have been shot with such rapidity. This makes sense given the enormous amount of time required to take a wet-plate glass negative and then develop it on the spot.

It can be seen that the area occupied by Heberton’s Lincoln in the first Gardner view is still the object of the spectators’ earnest and focused attention in the second Gardner plate. One thing which did change, however, is that all visible men on the rostrum are wearing their hats. The men who were hatless in the first view are now covered. This suggests that men who had uncovered their heads in the first view had done so out of respect for a person they had been viewing or a ceremony involving that person. Many accounts state how men on the speakers’ platform removed or doffed their hats in a showing of respect for Lincoln when he appeared before them. Colonel Henry P. Martin and the soldier peering over his right shoulder are prime examples. Between the shooting of the first and second Gardner stereos, those two soldiers returned their kepis to their heads after doffing them. The same stovepipe hat adorned by a mourning band in the first Gardner stereo view, is visible in the exact same location in the second stereo view (see the hat under the arrow, below).

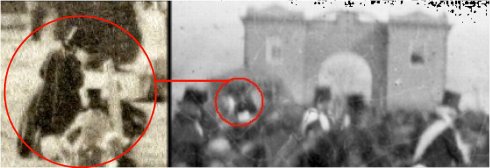

Only this time, the hat is partially fronted by the “ghost image” of a man’s face. The ghost image resulted from the fast movement of the man’s head. It can be shown that the man probably had bowed forward towards Gardner’s camera because the underside of the wide brim of his upward-tilted stovepipe hat clearly can be seen. The photographic capture of his ghost image resulted in rendering his face and his facial hair an opalescent white. Only his dark, deep-set brows remained true to their actual color. Along with his dark brows shaped like diacritical circumflex accents, his long nose is very similar to Lincoln’s and he appears to have deeply indented cheek lines as well as a beard covering his rounded chin. See below to view detail within the LC’s second Gardner photo, with a super imposed side-by-side studio image of Lincoln taken by Gardner in Washington, D.C. eleven days before the Gettysburg ceremony. Unlike the studio view, Heberton’s Lincoln’s lips are not pursed. His mouth is open and he appears to be smiling, explaining why his face is a bit longer than the studio image. There are no existing photographs of Lincoln smiling or posing with an opened mouth. This might be the only image we will ever see of him doing either.

Thus, it appears that the second view, for which there was a much longer time of exposure than the first view by a factor of 2 or 3 times as deduced by other visual evidence, captured two images of Heberton’s Lincoln: (1) his mourning band adorned hat seen in relatively good clarity and (2) a second and later exposure of his ghost image fronting that hat with the translucent face of Heberton’s Lincoln. The ghost image resulted either because Heberton’s Lincoln bowed his head forward and then raised it back up to reveal his face and hat in an up-turned position or possibly even after he reached down to deposit the boy seen on his saddle in the first view back to the ground. There are several accounts describing how Lincoln was not inclined to gesticulate with his hands, choosing instead to bow to his left or right from atop his horse to acknowledge the crowd’s reaction to him within the procession to the cemetery grounds. One reliable account even describes that Lincoln did not gesticulate with his hands during his now famous consecration oration, rather he bowed from side to side to emphasize various points within his short Gettysburg Address. From the context of what was going on around Heberton’s Lincoln in both the first and second Gardner stereo views which literally were taken “back-to-back” by the standards of 1860’s wet-plate photography, we know precisely where Lincoln was located thanks to the collectively focused gaze of the crowd and the presence of Lincoln’s special escort, Provost Marshal General Fry, a few feet behind him. The fact that the two Near-in-Time Gardner photos were taken in rapid fire succession, followed by a third view much more distant in time, establishes that Gardner was not merely taking generic crowd shots. The visual evidence, although not of the same quality as one might hope to obtain in a studio photograph taken from a distance of a few feet rather than outdoors from 80 to 90 yards with thousands of people present, also is supportive, albeit subject to more than one interpretation. But even what Heberton’s Lincoln wore is extremely supportive. Heberton’s Lincoln is the only Lincoln candidate wearing a mourning band. This is a critical observation independent of all of the other evidence. He also wore white gloves. Simply because the American intelligence community did not have a photograph of Bin Laden’s face before conducting their raid, the presence and actions of key people around Bin Laden gave them a sufficiently high degree of confidence that he was where they surmised he would be. As it turned out, they were right. The same holds true with respect to the Gardner stereo views. One doesn’t have to look at Heberton’s Lincoln images and declare that they are 100% matches to the studio images of Lincoln to which we all have become accustomed. Taken in combination with a well-reasoned evaluation of the comparative contextual details within each of the three Gardner scenes, Gardner’s true intentions are revealed along with the true location of Abraham Lincoln. Unlike Professor Christopher Oakley, I did not go searching in the hope of finding Lincoln within these photos. Instead, I studied these digital images originally to determine whether John J. Richter’s Lincoln is the “real McCoy” or if William A. Frassanito was correct in maintaining that Gardner only desired generic crowd shots because it was impossible for Lincoln to be anywhere other than seated upon the speakers’ platform completely obscured from Gardner’s camera. Mr. Frassanito, who has admitted in interviews to not being internet savvy, blogged through a friend in 2008 that in light of all of the evidence, “it seems evident to me that the two Gardner stereos were recorded subsequent to the occupation of the speakers’ stand by both Lincoln and the numerous dignitaries who followed him into the National Cemetery” and that Lincoln “would already have been seated on the speakers’ stand, patiently waiting for the ceremonies to begin, i.e., the speeches, etc.” For these and other reasons, he assigned a 20% probability that Mr. Richter and his colleague Bob Zeller had struck real gold rather than fool’s gold. See http://livingonthefield.blogspot.com/2008/01/william-frassanitos-problems-with-john.html. My book concluded that Mr. Frassanito’s position that Gardner’s photographs were mere “crowd shots” and not intended to capture Lincoln within any of the scenes is erroneous because an enormous amount of visual and documentary evidence says otherwise. Abandoning his prior position that Lincoln could not possibly be arriving at the speakers’ platform when any of the Gardner stereos were taken, Mr. Frassanito stated a new position in the October 2013 Smithsonian Magazine that he is 80% certain that Lincoln is visible in the second Gardner stereo view arriving, according to Professor Oakley, at the speakers’ platform. 80% is a very high number in light of the assignment of a failing 20% probability to the same proposition only 5 years earlier. Nearly all of the six or seven reasons cited by Mr. Frassanito in 2008 against the proposition that that the Gardner stereo views cannot possibly show Lincoln arriving at the speakers’ platform (including those articulated in a Civil War News interview conducted by Deborah Fitts) have not been affected in any way by the new ultra-high resolution scans obtained by Professor Oakley sometime during the first three months of 2013. That is because those now abandoned arguments merely were based upon a contextual interpretation of the views rather than the physical features of Richter’s Lincoln. His only remaining contention from 2008 against John Richter’s Lincoln candidate which still applies today is that the appearance of Richter’s Lincoln reveals that he “was undoubtedly nothing more than an anonymous, historically insignificant civilian official … that followed the dignitaries into the National Cemetery” and who was “hardly the focus of Gardner’s attention.” One of Mr. Frassanito’s 2008 arguments — that “Lincoln did not ride alone in the procession … [and] it is well documented that Lincoln was accompanied and flanked by several mounted civilians, including the chief marshal and three members of Lincoln’s cabinet (one of whom was six-feet-tall and undoubtedly wearing a hat). The individual identified by John appears to be completely unaccompanied by any mounted escorts [emphasis added]” — undercuts Professor Oakley’s position. Because Professor Oakley maintains that his candidate for Secretary of State Seward was seated in the first Gardner stereo view for ten minutes before Oakley’s Lincoln magically appeared out of nowhere in the second Gardner stereo view, Professor Oakley is left without any rational explanations for why everyone ignored and no one accompanied Oakley’s Lincoln in the second view … if he really is Lincoln. (Except as otherwise noted, all images hereinabove are courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.)

THE 150th ANNIVERSARY OF THE DEDICATION OF THE GETTYSBURG SOLDIERS’ NATIONAL CEMETERY

It was an honor to attend the 150th Anniversary of the Dedication of Gettysburg’s Soldiers’ National Cemetery on November 19, 2013. My thanks to everyone who made my visit an unforgettable experience. Please note that all of the images below are subject to a copyright in favor of Craig Heberton IV who reserves all rights. — Craig Heberton

Recent Comments