David B. Woodbury was a Civil War battlefield photographer who worked for Mathew B. Brady. According to Frederic E. Ray, Woodbury probably is the man seated on the left, below, in detail from an 1864 image at the Library of Congress’ Prints and Photographs Division (http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2012649238/):

A recent online auction offered for sale a collection of manuscripts — including a diary, notes, and letters — written by or belonging to David B. Woodbury (the “David B. Woodbury Collection”). The owner of the David B. Woodbury Collection noted in that auction that the diary and pertinent letters were enthusiastically reviewed in 1970 by Josephine Cobb, a pioneer in Civil War photography scholarship who worked for years at the Still Picture Branch of the National Archives and first identified Lincoln seated on the speakers’ platform in a Gettysburg photograph in 1952 (the “Bachrach photo”). Unlike a number of his colleagues, David B. Woodbury continued to work for Mathew Brady in Washington, D.C. even after Alexander Gardner struck out on his own. He is described by Frederic E. Ray as “arguably the best of the artists who stayed with Brady throughout the war.”

The 1860 Federal Census reveals that 21 year-old David B. Woodbury then lived in Norwalk, CT with the family of photographer and former jeweler & daguerreotypist — Edward T. Whitney. After learning wet-plate photography from Boston’s famed photographer J.W. Black, Whitney moved to Norwalk, CT in 1859 from Rochester, NY.

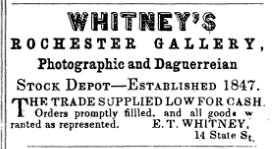

Ad in June 15, 1855 Humphrey’s Journal of Photography Vol. 07, n0. 4.

Ad in June 15, 1855 Humphrey’s Journal of Photography Vol. 07, n0. 4.

It is very likely that David B. Woodbury first met and worked for Edward T. Whitney in Rochester because the Woodbury family relocated from Vermont to Rochester after 1850 but sometime prior to the taking of the 1855 New York State Census when David was 16 years old. Consequently, David probably moved to Norwalk with Whitney in 1859.

Detailing some of his professional and wartime experiences, Edward T. Whitney reminisced in 1884 that:

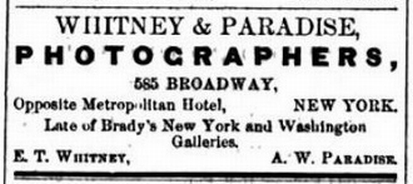

“[ I must allude] to the valuable aid and instruction I received from Mr. A. W. Paradise [in New York City in the late 1840s], who was Mr. Brady’s right-hand man so many years, and who afterward became my partner in business. Also to the courtesy extended to me by Brady and Gurney, in whose galleries I was accorded access … In 1859, my health becoming impaired by use of cyanide, causing constant headache and weak eyes, I went to Norwalk, Conn., to recruit. In three weeks I recovered my health and decided to sell out in Rochester. Leaving a successful business, I returned to New York, opened a gallery at 585 Broadway with Mr. A. W. Paradise, also one in Norwalk, Conn.

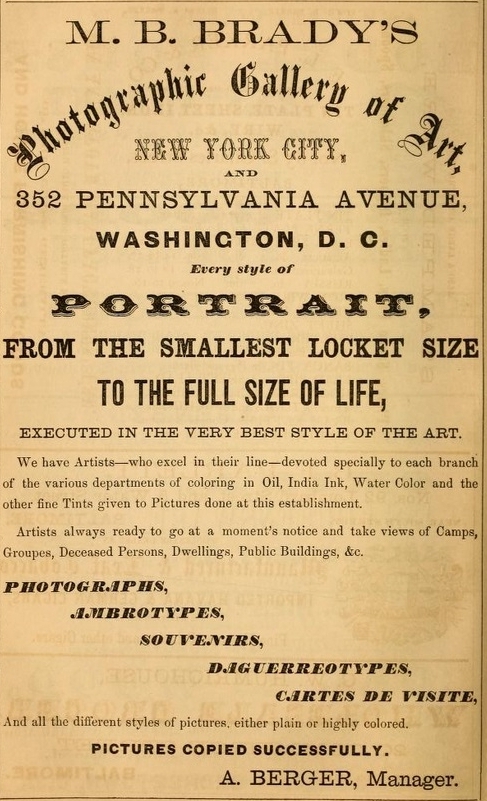

Business card in 1865 Trow’s New York City Directory

When the war broke out, Mr. Brady asked me to take my operator, Mr. Woodbury, and go into the field and make photographs for the Government of the scenes of the war. We went. Our first pictures were taken after the battle of Bull Run. We had a large covered wagon with two horses, and a heavy load of glass, apparatus, chemicals, and provisions … We spent the winter taking views of the fortifications around Washington and places of interest for the Government. But time will not allow me to go into detail of views taken at Yorktown, Williamsburgh, White House, Gaines Hill, Chickahominy, Seven Pines. During the seven days’ retreat from before Richmond to Harrison’s Landing, photographs were taken of James River from a balloon. At some other time, if desired, I may try to do justice to those times and scenes. Mr. Woodbury and myself were not the only ones connected with Brady in getting pictures of the war scenes … We endured the hardships of the camp, the difficulties of getting transportation, the sickening sights of the dead and dying, the danger of capture—and for what? To perpetuate for history the scenes of war, refusing to stop by the way to make portraits for money, which many were doing.“

Mr. Whitney’s account gives us a nice general overview of some of David B. Woodbury’s Civil War experiences for the period of 1861 through part of 1862. But what of the rest of the war?

As a sort of “teaser,” the owner of the David B. Woodbury Collection posted at his auction site a low resolution image of the first page of a letter written by David B. Woodbury to his sister, Eliza, dated November 23, 1863. Here is what I was able to decipher within that image:

“Washington

Nov 23, 1863

Dear Sister

I received yours of the 4th some time ago and was very glad to hear that you were doing so well and that Father and Mother … ??? … health. I was very sorry to hear of [Father?] being sick … wish to presume he is about well by this time. I went to Gettysburg on the 19th with Mr. Burger the superintendent of the Gallery here. We made some pictures of the crowd and Procession. We took our blankets and provisions with us expecting the crowd would be so great that not more than half would find lodgings. We found no trouble in getting both food and lodging.“

The “Mr. Burger” who accompanied Woodbury to Gettysburg on November 19, 1863 undoubtedly is Anthony Berger who had journeyed with Woodbury to Gettysburg from Washington, D.C. in July of 1863 shortly after the conclusion of the great battle [Berger is best known for a number of photographs he took of Lincoln at Brady’s Washington, D.C. studio, the most recognizable of which graces the U.S. Five Dollar bill].

1864 Boyd’s Washington [D.C.] and Georgetown Directory (1863), p. 288

After several days of familiarizing themselves with the Gettysburg battlefield terrain, they were joined in mid-July by their boss, Mathew B. Brady, whereupon they recorded a number of photographic views. Thus, Messrs. Woodbury and Berger were quite familiar with Gettysburg and some of its inhabitants from their extended visit to that place a mere four months earlier.

Of the nine known photographs taken in Gettysburg on November 19, 1863, none are attributed by modern day scholars or photo-historians to David B. Woodbury, Anthony Berger, Mathew B. Brady, or anyone else who then worked or freelanced for Brady. The first page of David B. Woodbury’s letter to his sister Eliza reveals that he was in Gettysburg on the 19th of November and took photographs there “of the crowd and Procession” with another Brady man, Anthony Berger. It leaves us wondering what other nuggets of information are inscribed in Woodbury’s November 23 letter, including descriptions of the events of the day and whether he and Berger took any photographs on the cemetery grounds. This single letter may or may not contain extraordinary information previously hidden from historians (other than Ms. Cobb) about both the dedication event and the photographs that these two men created.

Detail (below) from a photograph (LC) taken looking out over the Gettysburg Soldiers’ Cemetery grounds on November 19, 1863 shows a photographer on a ladder above his assistant, to the right, who is standing next to an apparent portable darkroom on a tripod. The view of them is slightly impaired by some leafless tree branches but there is no doubt that these men were photographers. Might they be David B. Woodbury manning the camera while perched atop the ladder and Anthony Berger standing next to the portable darkroom?

Some other questions have to be asked out loud — is it possible that Woodbury and Berger created any of the known Gettysburg images, such as, for example, the photo taken from a second floor window of the Evergreen Cemetery gatehouse attributed by William A. Frassanito to Peter S. Weaver (which would rule out them appearing in the above detail) or even the famous photo depicting Lincoln which Mr. Frassanito and others credit to David Bachrach? Might some or all of the Woodbury Gettysburg photos still await discovery in a dusty attic or a long-ago sealed box? Or were all of the glass plate exposures created by those men in Gettysburg on the 19th of November destroyed or placed somewhere forever out of our collective reach? Irrespective of the answers to these questions, the David B. Woodbury Collection may well constitute a gold mine for research into one photographer’s actions and experiences in Gettysburg on November 19, 1863 as well as at different times and places during the war.

Alexander Gardner mentioned in passing in his Sketchbook that he “attended the consecration of the Gettysburg Cemetery, and again visited the ‘Sharpshooter’s Home.'” David Bachrach commented briefly on his Gettysburg experience in a 1916 article, noting that he “did the technical work of photographing the crowd, not with the best results with wet plates, while Mr. Everett was speaking” and was then displeased with the 8″ x 10” “negatives” he took. Peter S. Weaver’s father wrote on November 26, 1863 that he “assisted Peter of getting a Negative of the large assembly on the Semetary [sic] ground, which I think is very fine, we have not as yet printed any Phot. of the Negative …” But it remains to be seen whether David B. Woodbury wrote in even greater detail elsewhere in his letter to his sister, some other letters, or within his diary about what he did and experienced in Gettysburg. Let’s hope that someday sooner rather than later the David B. Woodbury Collection is made available for scholarly review and analysis so that some of these questions can be answered and other new ones can be asked. In the mean time, the names of Messrs. David B. Woodbury and Anthony Berger appear to merit being added to the short and exclusive list of known Gettysburg dedication ceremony photographers.

— Craig Heberton IV, January 10, 2014

The cropped images in this post are all courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Recent Comments