Mathew B. Brady, Anthony Berger, David B. Woodbury, and at least one additional Brady assistant joined together in Gettysburg days after the cessation of hostilities in July of 1863. For perhaps a full week they focused their attention upon photographing the suddenly famous terrain. The public’s appetite to see what the field of battle looked like was whetted. Gettysburg’s fame had been earned as soon as the readers of the northern press digested lengthy and spell-binding accounts of the three days of fighting which culminated in a stunning defeat for Lee’s Army of Virginia. During their several days in Gettysburg, Brady’s men managed to expose 36 known photographic plates, mainly in stereoscopic format — an average of only about 6 a day. Likely a few months later in a tiny hamlet about 25 miles east of Gettysburg, some photographers took 6 outdoor scenes late in the afternoon of a single day, nearly all of which were shot in stereo. Although the location photographed was described by some unknown scribe as a “point of note during the invasion of Lee in 1863” (see below), those six hastily composed photos depict neither a battlefield, the home or birthplace of a famous person, the site of any important or infamous event, nor a place known to most Americans either then or now. Any evidence of damage wrought by Confederate cavalrymen was long gone by the time those photos were taken. Questions about why so many of those images were exposed, by whom they were taken, and what they depict have lingered and been debated for decades. Nearly a century after their creation, even the state in which the photographs were recorded remained a complete mystery to most of the National Archives curators.

William A. Frassanito writes in Early Photography at Gettysburg (1995), at p. 416, that Josephine Cobb, the former Director of the Still Picture Branch of the National Archives, shared with him several of her notes about her review of the contents of a private collection of papers written by David B. Woodbury covering some of the time period Woodbury worked for Mathew Brady. According to Mr. Frassanito, Cobb’s “notes indicate that Woodbury’s papers for July 1863 are missing, and made no specific reference to Woodbury having attended the November 1863 dedication ceremonies.” Two years later, Mr. Frassanito reiterated that “neither Brady, nor any cameramen affiliated with Brady’s firm, are known to have covered the November 1863 dedication of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg.”[1] Because the Woodbury papers remain in private hands and unavailable for research, photo-historians reached a dead end in their quest to determine if Brady or any of his assistants witnessed and attempted to photograph Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

But as revealed in “The Brady Bunch: The Case of the Missing Gettysburg Photos,” it is now known that within the David B. Woodbury private collection there is a letter from Woodbury which he penned from Washington, D.C. to his sister Eliza, dated November 23, 1863, which states in part:

“I went to Gettysburg on the 19th with Mr. Burger [sic] the superintendent of the Gallery here. We made some pictures of the crowd and Procession … We found no trouble in getting both food and lodging.”

Although the owner of that letter has confirmed to me that it does not disclose much more detail about what David B. Woodbury and Anthony Berger (then the superintendent of Brady’s Washington gallery) did in Gettysburg, this correspondence establishes that Brady sent the same two ace photographers who were with him in Gettysburg in July of 1863 back to that town about 4 1/2 months later to cover the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery and Lincoln’s presence there. No one, as of yet, definitively has identified any November 19, 1863 photos taken by Berger and Woodbury in Gettysburg, but those men may well have taken photographs en route to or returning from the Gettysburg cemetery dedication event.

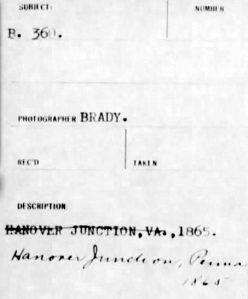

Mr. Frassanito has described a series of at least six negatives taken at Hanover Junction, PA, located about 25 miles east of Gettysburg, which are credited in “the earliest surviving identifications” to “Brady & Co.” See examples of two of the negative jackets from the collection of the National Archives, below:

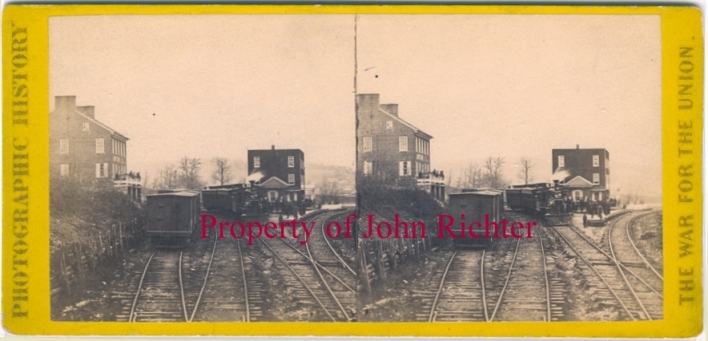

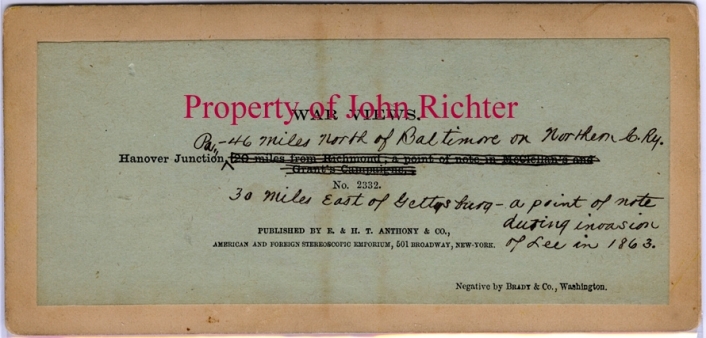

The oldest surviving captions from this particular series misidentified them as views of Hanover Junction, Virginia from 1864 or 1865. It is now well-established that they depict Hanover Junction, PA rather than VA. This conclusion is readily apparent when the images are compared to the surviving railroad depot in Hanover Junction, PA and what is left there of the extant tracks and rail beds. See, e.g., an article and corresponding “then and now photos” published in the Gettysburg Daily on December 3, 2008 at http://www.gettysburgdaily.com/?p=1121. Also, railcars of the North Central Railway (marked “NCRW”), which passed through Hanover Junction, PA, can be seen sitting at rest on an adjacent railroad siding in some of the photos. See “Crowds Await Transfer to Gettysburg for Dedication of the National Cemetery in Nov. 1863″ (March 7, 2012), at http://www.yorkblog.com/cannonball/2012/03/07/crowds-await-transfer-to-gettysburg-for-dedication-of-the-national-cemetery-in-nov-1863/, by Scott L. Mingus, Sr.

According to an article in the May 2, 1953 Gettysburg Compiler, entitled “More Brady Pix Discovered,” two grand nieces of Mathew Brady “discovered in Brady’s old studio” a book published two years before Brady’s death containing three of the Hanover Junction photos. That piece — The Memorial War Book (1894) by George F. Williams — is illustrated with dozens and dozens of photos attributed to the teams of Brady and Alexander Gardner and was the first published photo-engraved book of Civil War photography. The three Hanover Junction photos appear at p. 395 of that 1894 book, and are correctly represented under the master caption “Scenes of Hanover Junction, Pa.” Even more remarkably, they are placed in a grouping with images and text relating to the Battle of Gettysburg campaign. On June 27, 1863, Confederate forces raided Hanover Junction, cut the telegraph wires, tore up some railroad track, and burned the covered railroad bridge which spanned the adjacent Codorus Creek. They met with token resistance. By some unknown means that book’s author correctly determined where those photos were taken and used them to illustrate events in 1863 (see example, below). As revealed above, the National Archives notated in March of 1937 on the plate jacket of one of the Hanover Junction photos that the Virginia location was incorrect. But not until Josephine Cobb began the process of figuring out the correct location in about 1950 did the National Archives eventually change its descriptions for all of the views in its collection. See “Claim Photo in Times Was Abe Lincoln,” The Gettysburg Times, October 11, 1952.

Mr. Frassanito writes that “all of the available evidence, including the barren foliage, does tend to support [a] November 1863 dating” of the Hanover Junction views.[2] The manner of dress worn by the people posing in the images indicates that they were journeying to or from a formal event and points to a late fall dating. Several soldiers, young and old, can be seen with canes (in one case, a military man uses two of them like crutches), suggesting that they had sustained leg wounds and no longer were in active duty (see detail below from a gelatin silver print on a card mount, courtesy of the Library of Congress, which references the year 1863 in the item’s title). Blogger Andy Hall concurs with this assessment: http://deadconfederates.com/2013/08/03/stuck-at-hanover-junction/.

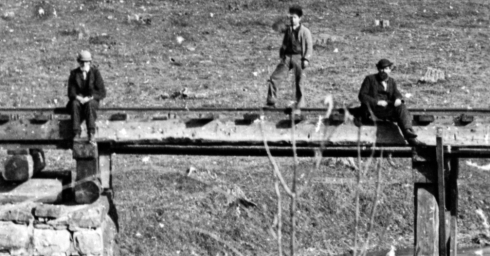

Might they have been wounded veterans of the Battle of Gettysburg traveling to or returning from the site of that bloody engagement, explaining why they (excluding the two men preening in the left foreground) and four bonnet-wearing women were the centerpiece of this particular view? Some or all of these apparently wounded men may have been convalescing nearby at the York General Hospital, located to the north near the North Central Railway station in York, PA, and found themselves stranded in Hanover Junction with passengers from Washington who had reached that place by passing through Baltimore at the southern end of the North Central Line. In summary, the Hanover Junction photos may reveal passengers who had come on two different trains from opposite directions and been deposited at the same station awaiting transport to Gettysburg. See also detail, below, from a different Hanover Junction view in which several soldiers (marked #s 4, 5, 6, 8 & 11) pose in a forward position for the camera with two young boys:

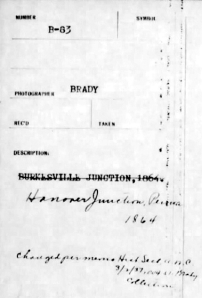

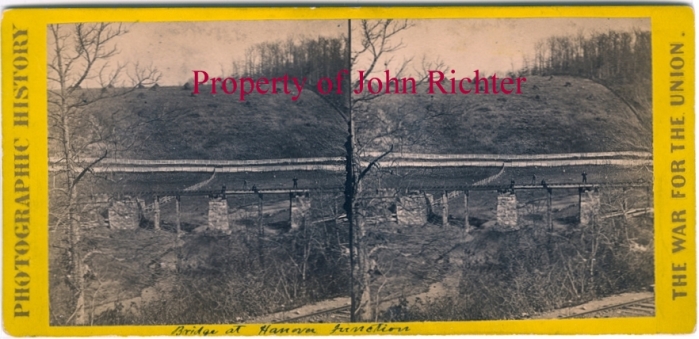

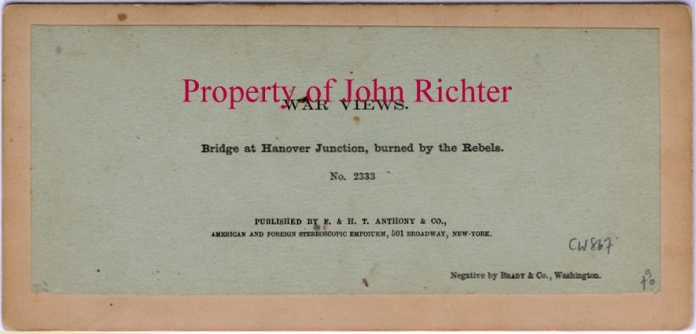

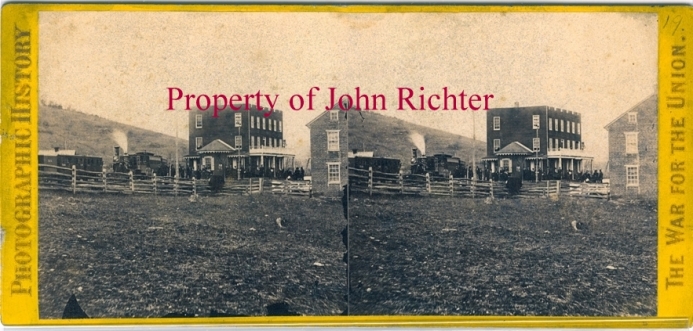

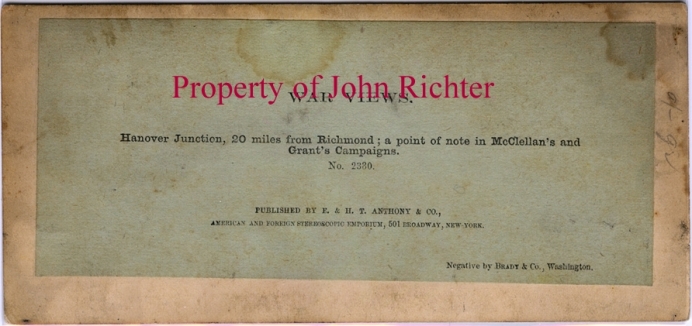

E. & H.T. Anthony & Co. contemporaneously published at least four of the stereo views taken at Hanover Junction in its The War for the Union series of stereocards, noting on each card’s backside that the negatives were by “Brady & Co., Washington” (See “The War for the Union, War Views” #s 2330, 2331, 2332, and 2333). Anthony & Co. also printed and sold other Civil War photographers’ works. If an Anthony & Co. stereo card identified Brady as the supplier of the negative, it can be said with a very high degree of probability that the photo was taken by a Brady photographer. For example, the front and back images of original Anthony “War Views” cards #2332, #2333, and #2330, taken at Hanover Junction, appear below, courtesy of John Richter. As can be seen, it appears that E. & H.T. Anthony & Co. was the first to mistakenly print the erroneous location for this series of photographs, leading the National Archives to later extrapolate that known troops movements near Hanover Junction, VA placed the photos in the 1864-1865 time period. Perhaps someone associated with the Anthony firm misread a poorly formed capital “P” as a capital “V” on a handwritten note from Brady’s D.C. gallery, thereby transforming “PA” into “VA.” Perhaps, too, that note accompanied duplicate slides of the four views to the Anthony’s place of business in New York City where they were printed and distributed as The War for the Union stereocards.

The Library of Congress attributes the Hanover Junction views to “Mathew B. Brady or assistant.” In summary, this information, Mr. Frassanito’s analysis, and the more recently gleaned evidence that Brady sent Berger and Woodbury to Gettysburg in November 1863, constitute substantial support for crediting the Hanover Junction series of photographs to Messrs. Berger and Woodbury.

Why might two Brady men have exposed photographic plates at, of all places, Hanover Junction? In short, all train passengers traveling from Washington, D.C. to Gettysburg, and vice versa, had to go through Hanover Junction, PA. It was there that two railroads met — the North Central Line and the Hanover Branch Line, the latter of which ran westward to and ultimately terminated in Gettysburg on the Gettysburg Railroad Line. It can be presumed that both Berger and Woodbury were transported to Gettysburg from D.C. by railcar in November of 1863, twice placing them in Hanover Junction. Because Woodbury’s letter to his sister specifies that he and Berger had no trouble finding lodging in Gettysburg, it is very likely that they arrived in Gettysburg no later than on November 17, 1863 — before the most substantial crowds descended upon the town in droves. This is a reasonable supposition in light of the several accounts detailing significant train delays and a huge volume of Gettysburg-bound passenger traffic on November 18 and 19, as well as the problems those late arriving out-of-town guests had in securing lodging. A reporter for the New-York World didn’t mince any words:

“The railroad facilities were very bad, especially between Hanover Junction and Gettysburg. I am informed that the best was done that was possible, but that may or may not mean anything. The passengers were compelled to crowd into dirty freight and cattle cars, and in that manner to ride a distance of some thirty miles, to their individual and universal discomfort.”

Another correspondent wrote that in Gettysburg on the night of the 18th, “hundreds slept upon the floors of the [churches,] inns and private residences, and hundreds more took a rigid repose in the [train] cars or carriages...” With only four ordinary-sized hotels and all Gettysburg-area residences overflowing, “there were many people walking the streets, unable to get any accommodations for the night.”[3]

Ward Hill Lamon, Lincoln’s former law partner from Illinois, the President’s de facto body guard, and the U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia, was selected to serve as the Marshal-in-Chief for the November 19 dedication ceremonies in Gettysburg. To this end, on November 17, he made the journey from Washington to Gettysburg along with a number of judges, politicians, journalists, dignitaries, and friends, several of whom were to serve as Lamon’s aides at the National Cemetery dedication ceremonies on the 19th. The Ward Hill Lamon Papers at the Huntington Library reveal that twelve men who agreed to serve as aides signed a petition “signifying their intention of accompanying Marshal Lamon to Gettysburg tomorrow — leaving this city at the hour unnamed (undated).” Among the men accompanying Ward H. Lamon were Robert Lamon (his brother), Benjamin B. French, Judge Joseph Casey, John W. Forney, Solomon N. Pettis, John Van Riswick, Noah Brooks, and Simon P. Hanscom. One of the several journalists who accompanied Lamon on the 17th (perhaps John W. Forney) wrote the following account, published on November 18 in the Philadelphia Press and the Washington Daily Morning Chronicle:

“[Mr.] Lamon and a number of his aids … left Washington this morning, at a quarter past eleven o’clock, for Gettysburg, in special cars, kindly provided by W.P. Smith, of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. They arrived in Baltimore at one o’clock, and repaired to the Eutaw House, where a sumptuous dinner was partaken of, by the courtesy of Mr. Smith. At three P.M. the party left for Hanover Junction, in a special car furnished by the officers of the North Central Railroad. Here we are detained, no car being ready to convey the party to Gettysburg.”

Given Mathew Brady’s high profile, it is possible that Lamon invited the head of Brady’s D.C. photography studio, Anthony Berger, and his colleague, Mr. Woodbury, to ride with him to Gettysburg — for free, no less. If Messrs. Berger and Woodbury did find themselves stuck with Lamon in Hanover Junction in the mid-to-late afternoon of the 17th with a lot of time to kill waiting for a connecting train to Gettysburg, it would explain why they had the opportunity to unload their photographic equipment and expose several plates in Hanover Junction. But it still doesn’t fully explain what motivated them to unpack and deploy their precious photographic cargo, let alone to expose six outdoor plates at a location where neither a major battle nor even a significant military skirmish between opposing forces had been fought. See, for example, detail from one of the photos (below) showing what John Richter has identified as the photographers’ portable darkroom positioned along a fence line adjoining one of the tracks.

The author of “Crowds Await Transfer to Gettysburg for Dedication of the National Cemetery in Nov. 1863,” noted above, estimates that a Hanover Junction photo reproduced below was taken at approximately 4:00 p.m. on November 18, 1863. If the time of day is correct, it would fit into the timetable for when the Lamon contingent was stranded in Hanover Junction waiting for a connecting train to appear on the 17th. As noted in the October 11, 1952 edition of The Gettysburg Times, “shadows indicate the time of day would be shortly before [a November] sunset.”

In one of the Hanover Junction photos, two men stand prominently atop a parked train car hitched directly behind a locomotive (see a print on a card mount in the Library of Congress collection, below; this print was cropped down from the more expansive National Archives B-83 negative). They are the most discernible people in the print and possibly the chief targets of the cameramen. Perhaps the men standing atop the train are Ward H. Lamon and his brother Robert, who performed the duties of a marshal’s aide for his older brother at the Gettysburg dedication ceremonies? Robert, who also served as a Deputy U.S. Marshal under Ward H. Lamon in Washington, was then 28 years old; his older brother was 35.

See detail, below left, of the two men as well as detail, below right, featuring them prominently within a different Hanover Junction view taken looking towards the eastern-facing side of the depot.

Compare these men with an undated studio photograph of Ward Hill Lamon (courtesy of the Library of Congress, below left) credited to Mathew Brady and a carte de visite of Robert Lamon from about 1864:

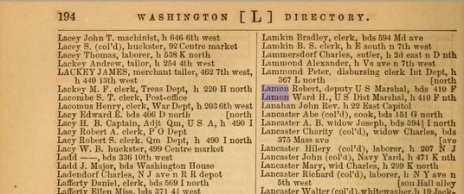

Is it possible that they are the same men? Might this explain why Berger and Woodbury exposed several of their precious glass plate negative slides even before they arrived in Gettysburg? The Lamon brothers’ entries in the Washington, D.C. City Directory for 1864, below, reveal that Robert then boarded with his older brother’s family:

The goateed man with the bowler hat also appears in a stereo view scene depicting a railroad bridge over Codorus Creek (see below, in close-up detail, courtesy of the Library of Congress). The approximate center point of that North Central Line bridge, where the man sat, is no more than about 250 feet from the eastern side of the Hanover Junction railroad station. The camera was set up about 400 to 500 feet from the station house next to the Hanover Branch Line tracks and faced the Codorus Creek bridge looking in an east by northeasterly direction. The sunlight cast on the man illustrates that the plate was exposed late in the afternoon when the sun was low in the southwestern sky. I estimate the distance from the camera to the man on the bridge at about 325 to 375 feet. Was Ward H. Lamon the sort of man who might have walked out onto a train bridge, sat on the end of a railroad tie in the middle of the bridge, and there dangled his feet in order to pose for a stereo photograph? Would Anthony Berger or David Woodbury have asked W.H. and Robert Lamon to do such a thing, let alone climb atop a railroad car, or might Ward H. Lamon — Lincoln’s self-proclaimed bodyguard and the U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia — have directed the camera operators to photograph him and his brother in several poses demonstrating their virility?

Three other males joined the goateed man on the bridge. Only one of them also sat on the end of a railroad tie, but that man chose a somewhat safer spot where his feet firmly rested upon a large, squared log directly above one of the bridge’s massive stone foundations in the middle of the creek. He is the same fellow seen standing with the goateed man in the two other Hanover Junction views previously discussed and who may be Robert Lamon (see a comparison, below).

Is the goateed man Ward Hill Lamon, who was captured in this and two other pictures by the photographers as a form of payback for providing free transportation to Gettysburg, or is he simply a historically irrelevant figure with a goatee who prominently inserted himself (along with a younger man) into three generic Berger & Woodbury views which were taken only with the object of photographing buildings, structures, and equipment rather than specific people or groups of significant people in various scenes?

Because the only other people photographed on the bridge are a boy shielding his eyes from the sun with his right hand (see above) — standing between the men who may be the brothers Lamon — and one of the interloping men preening before the camera in the view showing military men and several women on the station house platform (see a side-by-side comparison, below), it appears that the goateed man and his side-kick again were the primary human subject matter posed within a Hanover Junction photographic view taken by the Berger-Woodbury team.

In his book The Gettysburg Soldiers’ Cemetery (1993), Professor Frank L. Klement describes Ward H. Lamon as “stout, most handsome, and possessed of a swashbuckling air.” Despite an apparent penchant for casually striking swashbuckling poses and the strong resemblance of his side-kick to Robert Lamon, is the goateed fellow burly enough to be Ward H. Lamon? Would Lamon have been inclined to cut his hair that short before he served as the Chief Marshal at the Gettysburg Soldier’s Cemetery dedication event? Was Lamon clean-shaven or sporting a goatee in November 1863? Part of the difficulty in making any conclusive identification of the possible Lamon figure is that there are not, to my knowledge, any dated photos of him from 1863, let alone in the fall of 1863, to use as a basis of comparison. A hatless man with a goatee seated next to Lincoln on the Gettysburg speakers’ platform visible in the so-called David Bachrach photo taken on November 19, 1863 might be W.H. Lamon, but it is more likely that he is one of Lincoln’s personal assistants — John Nicolay — given where he is seated. Whether or not Ward H. Lamon is in the Hanover Junction views, however, is a mere sidelight to a bigger question. Again, quoting Professor Klement, he writes: “on the next day, November 18, most of Lamon’s friends and aides toured various parts of the vast battlefield [in Gettysburg].” If Messrs. Berger & Woodbury accompanied Lamon to Gettysburg on the 17th, they probably revisited portions of the Gettysburg battlefield on the 18th, perhaps even famous locations they had missed in July such as Meade’s headquarters at the Lydia Leister house or Devil’s Den. It is exciting to speculate that these men took more Gettysburg battlefield views which have yet to be discovered.

Whereas searching for the tandem of Ward Hill and Robert Lamon was not the impetus behind this review of the Hanover Junction photos, other researchers have engaged in the search for Gettysburg dedication ceremony luminaries in the Hanover Junction images for more than a half century. For a number of years particularly Thomas Norrell, a collector of old locomotive photos, and Russell Bowman, President of the Lincoln Society of Hanover Junction, argued that President Lincoln is visible in at least one of the Hanover Junction views. Their position first was made public prior to Josephine Cobb’s November 1952 disclosure of Lincoln’s visage in a Gettysburg Soldiers’ National Cemetery dedication photograph. Until then, it was “pretty well agreed [by and among Lincoln scholars] that the Great Emancipator was never photographed either at or on his way to Gettysburg, Pa.” The Gettysburg Times, October 11, 1952. The advocates of Lincoln’s presence in at least one of the Hanover Junction photos — the one depicting two men standing atop a parked train car, seen above — assert that a whiskered figure in a stovepipe hat standing largely unattended on the platform near the locomotive is President Lincoln. That same man also appears in a second stereo view clutching, again, an umbrella with a black gloved hand. He is posed in the second photo near several large trunks (see detail below, Library of Congress).

When originally disclosed to the media, the top photo, above, created a “buzz” as it was held out as the possible first photographic discovery of Lincoln’s image in connection with his visit to Gettysburg. After the Western Maryland Railway Company released the photo in early October 1952 “calling attention to the ‘tall man’ in the stove pipe hat … experts and amateurs alike jumped into the controversy. Art editors sent the photo throughout the country. Life Magazine pondered the problem and set the prints before its readers.”[4] One of the arguments asserted in support of the “Lincoln was photographed at Hanover Junction” theory is “the fact that the picture was made at all by the famed Brady … indicate[s] an event of some importance in Hanover Junction.” This argument actually supports dating the photographs to November 1863 in that other than traveling to and from Gettysburg, there is no other explanation for two Brady photographers being in and taking pictures at Hanover Junction. And the only two times Brady photographers are documented to have been in Gettysburg during the Civil War are in July and November 1863. When they were there in July, moreover, the Codorus Creek railway bridge was burned down and the military controlled and used the the rail service to transport supplies and the wounded between Gettysburg and, for example, the York General Hospital, to the exclusion of civilians. The passengers visible in the Hanover Junction views are a mix of soldiers and mostly civilians and the context of those photos coupled with the amount of time over which they must have been shot strongly suggest that the passengers were waiting for a Hanover Branch Line train to arrive which could ultimately get them to Gettysburg via a connection in the town of Hanover to the west.

Despite initial skepticism over — and even out-right rejection of — the claim that Lincoln was photographed at Hanover Junction expressed by notables such as Ms. Cobb, numerous Lincoln scholars, and photo-historians, The Gettysburg Times on June 17, 1953 described the photo in question as “the famed Hanover Junction picture, which many claim depicts Lincoln enroute to Gettysburg.” Nearly twenty-five years later, a March 1, 1988 Gettysburg Times headline proclaimed “Historians Still Debate if Photo is of Lincoln.”

Without now parsing through the several contextual arguments running counter to the “its Lincoln at Hanover Junction” theory, I’ll simply note that today’s high resolution digital scans reveal that the man does not look at all like Lincoln. Moreover, if Ward H. Lamon and his brother Robert are visible in several of the Hanover Junction views, then the whiskered man cannot be Lincoln simply because Lamon traveled to Gettysburg the day before Abraham Lincoln left Washington (Lamon’ role as Lincoln’s body guard and escort was filled by Provost Marshal General James B. Fry during Lincoln’s visit to Gettysburg). Which leads us back to some remaining questions — are these views merely generic scenes of the Hanover Junction railway station and surroundings taken in November 1863 which just happened to be populated with a number of stranded passengers or did the photographers compose these images purposefully and place a specific person or persons of notoriety in one or more of their stereoscopic scenes? Also, assuming that the images, in fact, were exposed around the time of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, did Anthony Berger and David Woodbury take them on the way to or back from Gettysburg? If Berger and Woodbury took these views in connection with their now documented trip to Gettysburg, what happened to the views they took in Gettysburg of “the crowd and Procession?” How is it that four of their Hanover Junction views were published by E. H. & T. Anthony & Co. but none of their Gettysburg dedication event views are known to collectors and historians? Ah, the secrets that have yet to be revealed …

By Craig Heberton, May 4, 2014 (to be continued)

————————————

[1] William A. Frassanito, The Gettysburg Then & Now Companion (1997), at p. 58

[2] Ibid.

[3] Timothy H. Smith, “Twenty-Five Hours at Gettysburg,” Blue & Gray Magazine, at p. 14 (Fall 2008), quoting “Dedication of National Cemetery,” Gettysburg Star and Banner, November 26, 1863 and Daniel A. Skelly, “A Boy’s Experiences During the Battle of Gettysburg” (1932) at p. 26.

[4] The Gettysburg Times, January 1, 1954.

Recent Comments